1934

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #165. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Kcab ti nur.

———

Dear Reader.

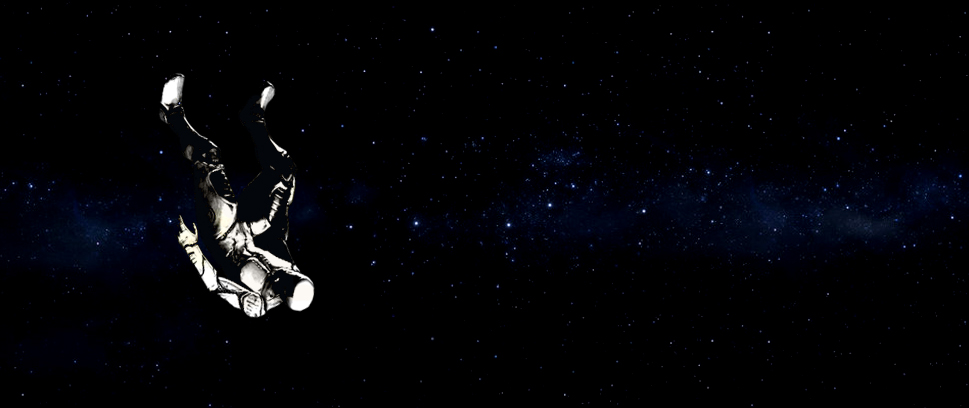

I hope your time jump has been rather prosperous. It’s rather stunning that all these strange and wonderful means of exploration have been made possible by our friends in the time beyond, even if there is the odd space-time rupture here and there.

In any case, let’s skip the pleasantries and get onto more important business.

That abominable woman Marmott had a party at Heath’s Club – I told her you won’t be there, tummy issues.

Now your options left are Minshaw and Billet, now Billet would be the done thing, get a real taste of the fashions de jour of the era and there are always spare rooms and servants for guests, one wonders how they manage in this day and age!

Minshaw is much smaller, more…selective, the real miscreants of the age gather in an awfully quaint little flat in Soho. Occasionally even those with a little blue blood have been rumored to have slipped in between the dens of ill repute to find their way in.

The option is of course always is yours dear, but I know where my bread is buttered.

With love,

Your trusty time travel guide

Dear Reader,

Marmott is asking after you again, wants to go see one of Shakespeare’s more dull plays. You’d think she’d have the decency to invite us to a comedy, at least then they wouldn’t know if we were laughing at the show or their wooden acting!

In any case, let’s move to the focus of this letter, A Handful of Dust by Evelyn Waugh, a satirical novel about the dwindling English upper crust of the time in which we find ourselves. In this, we largely follow the Last family, composed of Tony Last, Brenda Last and their son John Andrew, minor nobles who all live in a crumbling gaudy stately home where each room is named after a knight of the Arthurian round table (Galahad is the one where they send guests who they don’t want staying another night). While things start fairly sweet on their face, as the novel progresses the plastered over cracks show and are eventually torn wide open with a tragicomic ending that is at once out-of-left-field and also entirely coherent.

The main targets of Waugh’s wit in this novel are the upper class of the era. After the devastating effect of the First World War, the already-strained aristocracy was finally properly tangible, with the economic effects of the war (and personal losses) throwing their position into disarray. Furthermore, the deaths and/or traumatizing of many of the young men on the battlefield weakened the ability of patriarchal power enforced through legacy to truly take hold. Waugh is incisive in his takedown of a class of people who were lost and circling the drain. In particular, the sharp end of his pen is directed at the institution of marriage.

Waugh’s heteropessimism (likely informed by his own bad marriage and deeply complicated relationship with his sexuality) is sharp and unrelenting. In the upper-class society Waugh presents, affairs are not some grand moral sin or betrayal, but instead are expected, the done thing to keep from the tedium of hereditary wealth. The only real question is how such an affair could be conducted. So, we end up with pages of attempted adultery set-ups that go wrong and wild and sometimes correct speculation. Even the mechanisms of divorce are banal in ways that Waugh wrings humor out of; there’s no grand shouting match or breakdown, just curt phone calls, even curter telegrams and staged cheating dramas to fill court documentation. Time after time, bourgeois marriage is shown for what it is, not an expression of love or passion but just another property contract. The people (and especially the women) involved are just chips to be traded and shuffled around.

This iconoclastic approach to the lives and institutions of the wealthy is a powerful one – especially in a country so fixated on the aesthetic traditions and customs of class. When the lie of a quasi-divine right to dominate is taken away, space is opened up for moments of change and the powerful become mortal. In some ways this feels extremely pressing in our current age, where digital cultures (and also the ways they are manipulated) means that the powerful are both closer to us than they’ve ever been (often through online temper tantrums) and more ephemeral than ever. With big institutions of 21st century capital like Silicon Valley and various stalwarts of venture capital stalling or outright crumbling it feels inevitable that like in Waugh’s era a change is coming – the only question is what.

What is perhaps most fascinating about reading Waugh’s work from the perspective that I (and likely you) take is that his work is actually doing all these critiques from a very conservative perspective. While he skewers the upper class it’s not because he agrees that wealth should be redistributed from few to the many, or that the decline he analyzes is a result of interwoven heteropatriarchy and capital. Instead, for him the malaise which I would say was brought to bear by colonial Christianity and the dwindling empires matching under its banner, can actually be saved by proper Christian morality and adherence to the correct (see: white supremacist) social order.

Where his ultimate allegiance to the powers that be comes through clearest in how he refuses to lend any humanity to the few working class and non-white people in the novel.

The main working-class characters in the Last estate exist as stock character extensions of the household and don’t get any complexity beyond that – we don’t even learn Nanny’s name. Ben the stable hand is a nothing character whose main role is to be the means by which some (pretty funny) jokes can happen with John Andrew blurting out various obscenities and he disappears as soon as the child stops being part of the central narrative. The pair of sex workers introduced in the divorce farce are not exactly disparaged, but again they are more like narrative instrument without much depth beyond that.

Where the British working class are silly stock characters, the Indigenous people in the ending of the novel, which pulls heavily on Heart of Darkness as Tony Last takes a doomed expedition into the Amazon, are more like a barbarous force of nature. There is an interesting potential for an anticolonial critique of the upper class here. He goes on this trip to find an unnamed doomed city as a means of getting away from the divorce drama. Part of the ridiculousness of this though is that it’s the 1930s. While large swathes of the Amazon weren’t known in ways that were legible to Westerners, there is no great frontier of colonial glory to be gained, Brazil had in fact gained its independence over a century before and most European colonies would be (formally) released from colonial rule in the next few decades. In line with the rest of Tony’s character he is sleepwalking through the footsteps of his ancestors but can’t make it actually work for him.

The problem here, as with Conrad’s story and most of its imitators, is that the ridiculousness and gravity of Last’s situation and cluelessness must be created through dehumanizing the Indigenous populations. The indigenous people here are hapless and malleable with ‘silly’ traditions and ‘broken’ English. Then Tony’s eventual tormentor is a man that’s framed as being both childlike and menacing by nature of his isolation and mixed European and Indigenous blood. In operating with Indigeneity as a pollutant, Waugh’s well-recorded racism comes to the fore, not to mention his free and flowing racism against the Black Brazilians that feature here. At every point non-white people are curiosities or active evils but never fully embodied.

It would be wrong to lay the blame singly at Waugh’s feet though. The generation of artists from which he emerges (the Bright Young Things) were often critical of the context in which they emerged, but still were very much products of it, with artists like Duncan Grant at points turning that English middle-upper class curiosity with the racialized into fetishization. Beyond that, many also pulled heavily from the Harlem Renaissance and the many unsung Black progenitors of the massive shifts in the artistic landscape that happened at the start of the 20th century.

In this case it seems dear reader, that the enemy of our enemy is not quite a friend – or at least they’re one who we shouldn’t invite to stay in our home.

Speaking of enemies, I fear I may have made one or two at the Minshaw table whose blood was bluer than I anticipated. I forgot that these fellows haven’t quite learned the art of pretending to be middle class when you hear an Eat The Rich joke. So I reckon we’ll be leaving this time rather soon and be onto the next lest things get a little too sticky with the treason allegations.

See you soon,

Your trusty time travel guide

———

Oluwatayo Adewole is a writer, critic and performer. You can find her Twitter ramblings @naijaprince21, his poetry @tayowrites on Instagram and their performances across London.