The Kosmische Cosmos

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #163. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

The Burnt Offering is where Stu Horvath thinks too much in public so he can live a quieter life in private.

———

To accompany this essay, I’ve prepared a two and a half hour playlist of bleepy bloopy music to either relax you, distract you or to induce in you a minor panic attack, depending on how you feel about bleeps and bloops.

1.

About a year ago now, I went into the kitchen to make breakfast and the radio was on, tuned, as ever, to 91.1 WFMU, our local freeform radio station. One of the delights of listening to WFMU is that you never really know what you’re going to get; it’s a radio station arranged around digression. Even the DJs who adhere closely to the stated themes of their shows often find themselves wandering afield every now and then.

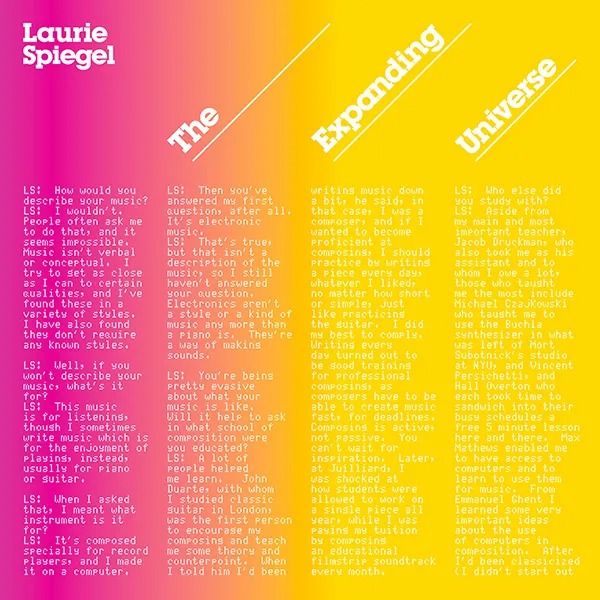

This particular Thursday, the most perfect sort of electronic music was coming out of the speakers, the sort that stopped me dead and made me stand there for however much of the 14-minute-ish runtime was left. I then got my phone out, looked up the song on the live playlist on WFMU’s site: “East River Dawn,” by Laurie Spiegel. I immediately bought the record – The Expanding Universe, the most recent reissue of a 1980 collection of Spiegel’s algorithmic music produced at Bell Telephone Labs during the ‘70s.

“East River Dawn” features a set of four or so synthesizer “voices” that wrap around each other and transform over time. That constant change combined with the length of the composition makes it difficult for me to keep track of the voices, to the point that while the beginning and ending always sound the same, you could tell me that everything in between was entirely new every time I listened and I would believe you. I get lost in the song’s warmth, and the way it evokes something of days past. It isn’t nostalgia, really – that’s a sentimental longing for a past experience now forever out of reach – but it represents the essence of how I believe the late ‘70s sounded. “Anemoia” is perhaps closer: a word that the Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows coined as a longing for something you’ve never known. When I read the liner notes and saw that the song was used for an outdoor dance performance in Manhattan in 1975, “blaring out over big speakers on a sunny summer day,” I was a bit sad I missed it (despite, you know, not having been born yet).

The whole record works the same sort of magic (and packs an emotional wallop that is the exact opposite of the charges of “coldness” that critics tend to level at early electronic music). Of course, I wanted more, but I had trouble finding anything that fit the bill. This is partly, I think, because of Spiegel’s background – before working in experimental electronic music, she studied folk music for a variety of instruments. I can hear echoes of those more traditional modes in The Expanding Universe. I suspect a lack of similar grounding is the reason why I bounced off many of Spiegel’s contemporaries in the New York City scene (who do, in fact, strike me as a bit chilly). Spiegel herself left the scene in the early ‘80s, feeling it was becoming commoditized. Her next collection of music, Unseen Worlds (1991), is darker and more dissonant. It didn’t scratch the same itch for me, and thus, I gave up. One perfect record encapsulating all of ‘70s electronic music is better than none.

2.

I found the key on another Thursday, earlier this year. Another breakfast. Another chance encounter with This is the Modern World on WFMU – the DJ, who goes by Trouble, certainly earns her namesake when my wallet is involved. This was the second time that day she got me, in fact – an early song in her set introduced me to minimalist composer Sarah Davachi and now I have four of her LPs on my shelf. Again, I passed by the radio and got stopped in my tracks by electronic bleeps and bloops that pulled me to a different place. This was “Wait Here Now,” by The Advisory Circle, a song that hit enough of the same aesthetic notes as “East River Dawn” that it seemed almost uncanny. I felt a door open.

Full Circle, the Advisory Circle album in question, came out in 2022, but I’d be hard pressed to gather that from merely looking at it (or listening to it, though there are hints in the mastering that are distinctly 21st century). The cover is a black and white photo collage of Brutalist and mid-century architecture punctuated by people (and bits of people) garbed in early ‘70s fashions. A martini glass features prominently in the lower right corner. In the background is a geodesic dome and silhouettes of people dancing. In sum, the image seems to be conveying that a good time happened at some point. When? That’s an open question. The Advisory Circle seems unmoored in time.

The music is consciously retro, but not an exact reconstruction of anything particular. I hear strains of commercial jingles and theme songs to British television shows and the sort of melodies that would back the safety films I saw in school in the ‘80s and ‘90s (most of this style of music was likely recorded in the ‘60s and ‘70s as “library music,” produced in bulk, stored and licensed out to TV, radio and other media as needed). There is a warble in the sound, too – the telltale distortion of a tape played too many times, the hiss of static – that implies both age, the agency of preservation and just a hint that, under the chipper surface, something is subtly wrong.

3.

In the upper right-hand corner of Full Circle’s cover is the number “42,” indicating that this is the 42nd release from the label Ghost Box, which describes itself as “a record label for a group of artists exploring the misremembered musical history of a parallel world. A world of TV soundtracks, vintage electronics, folk song, psychedelia, ghostly pop, supernatural stories and folklore.” I consider this an accurate self-assessment, but go ahead and listen to the complete catalogue playlist and decide for yourself. Founded by Julian House and Jim Jupp, the pair lead this aesthetic experiment (and lightly narrative puzzle box) by example, using the label to release a number of albums for their own various projects: House records primarily as The Focus Group and Jupp as Belbury Poly. Many other artists and projects have found a home on the label, with some dipping in for just a sonically appropriate single or two.

Ghost Box releases all have a similar visual appeal, thanks to House’s graphic design skills, which draw from specific aspects of British cultural output from the late ‘50s to the late ‘70s. So: science textbooks, brochures, Kodachrome and Polaroid photography, BBC television productions and more. As with Full Circle, they generally present a smiling face. There’s a kind of (pseudo-)scientific optimism here. Photos of smiling children are common. The fonts are smooth and serif-free. Yet something feels distinctly wrong here.

The music follows suit. Under bright tones and surprisingly pastoral swirls, there is a real darkness. The first Belbury Poly LP, The Willows (2004), is a good example. Jupp’s recording moniker takes its name from the town of Belbury, in C. S. Lewis’ novel That Hideous Strength (1945). That fictional town houses the headquarters of a nefarious scientific research organization that is searching for the corpse of Merlin, among other mystically-geared pseudo-science projects. The title of the album is shared with one of Algernon Blackwood’s most famous horror tales, which, at its most basic reading, involves an encounter with carnivorous trees from another dimension (maybe). And the music? A mix of warm synths, grit-toothed cheerfulness, muted folk chants and increasingly menacing washes of organ. It is no surprise then that Jupp has also recorded under the name Eric Zann, a reference to Lovecraft’s Erich Zann, a character whose frenzied viol-playing sees him carried off by unknowable entities. Or that Ghost Box 09, The Séance at Hobs Lane (2007) is a nerve-jangling re-score for Quatermass and the Pit, Nigel Kneale’s masterful melding of science fiction and folk horror. If the next Ghost Box release were to be purportedly recorded by Windhollow Faire, the haunted acid folk band at the center of Elizabeth Hand’s novel Wylding Hall (2015), I wouldn’t be surprised in the least.

Like Wylding Hall and the works of Nigel Kneale, the slightly sinister music of Ghost Box taps into a notion that there is, perhaps, a deeper real lurking under the shiny veneers of modern society: a substrate of folklore and old gods and magic that provide something that is, if not more true than waking life, an experience that is equally valid, though more obscure.

4.

Some music critics refer to this as Hauntology, a specifically British manifestation of electronic music that, rooted in nostalgia, memory, time loops, urban legends and interactions with utopian optimism, supposedly speaks to some shared, localized cultural experience – perhaps the best-known electronic band fitting the bill is the Scottish duo Boards of Canada. And sure, a lot of this stuff I’ve gotten into is British, and you can hear glimmers of the sound in older UK acts like Portishead and Tricky. But then on the other hand, how do folks playing in the maze of genre and sub-genre square the clear influence of John Carpenter’s distinctly American music, particularly his work with Alan Howarth on the scores for Halloween 3 (1982) and Christine (1983)? Or the instrumental tracks from Nine Inch Nails, the most successful exponents of the American industrial sound (at least until Atticus Ross joined and Britished it up; he hails from Ladbrook Grove, which sounds like a very Ghost Box sort of place)? Or the fact that all of this music has a common German ancestor in what used to be called Krautrock (specifically the spacey vistas of Tangerine Dream) and now is more often referred to as Kosmische Musik, or cosmic music? Where does the work of Wendy Carlos, especially for the film The Shining (1980), fit in to this silly British sub-genre? What of synthwave and dungeonsynth and all the other sub-sub-genres clustering around the same crossroads?

Parsing genre is a fool’s game.

5.

Out of the stable of Ghost Box artists, I’ve fixed on Pye Corner Audio, a project of Martin Jenkins but often credited as the work (or product of exploration) of the “Head Technician.” Pye Corner has released four albums and a number of singles with Ghost Box that are closely aligned with the label’s established aesthetics. They’ve also released piles and piles more, all of which experiment in different directions, particularly with sounds in line with trance and rave music (the secret warehouse parties of those scenes in the ‘80s and ‘90s evoke a different sort of folklore, but folklore nonetheless).

Pye Corner Audio’s first release, though, was the Black Mill Tapes, the first volume of which appeared in 2010. The conceit is that the music was reconstructed by the Head Technician from a box of moldering reel-to-reel tapes found at a weekend auction in a small village called Coldred. They’re full of weird audio artifacts, distortions, static, breaks and other noise. The tone of the music, coupled with track titles like “We Have Visitors” and “A Dark Door,” starts to tell a story through implication – probably the sort of story where the protagonist dies at the end. This thread has continued subtly, with evocative titles for EPs, like The Black Mist (2014), and explicitly in the liner notes of their first Ghost Box album, Sleep Games (2012), which describe strange experiments and anomalous activity in the “concrete tape” of the buildings that make up modern (fictional) Belbury.

The Night Monitor (Neil Scrivin) dispenses with subtlety entirely – the four albums under that banner are explicitly designed as soundtracks for unnatural incursions: This House is Haunted (2019) takes on the famous 1977 case of the Enfield Poltergeist, Spacemen Mystery of the Terror Triangle (2020) tackles a series of UFO encounters in South Wales in the late ‘70s, Their Dark Dominion (2022) looks at the occult doings in Clapham Wood and Close Encounters of the Penine Kind (2023) scores the alien abduction of policeman Alan Godfrey in 1980. Nostalgia and utopianism fall away as well – these albums sound like the soundtracks for episodes of a documentary television series like In Search of… (1977 – 1982) or Unsolved Mysteries (1987 – 1997). They heighten the anxiety and drama around these supposed supernatural events in ways that are both deeply sincere to the point of being emotionally unsettling, but also so over the top they can only be described as either tongue-in-cheek, or horrifically campy.

Then there’s the entirely un-supernatural Kosmischer Läufer, a five-album series (one for each Olympic ring), collecting “The Secret Cosmic Music of the East German Olympic Program 1972-83.” Credited to Martin Zeichnete, the first album appeared in 2013 and the final installment just recently came out in 2023 (the same day I discovered the project, oddly enough). The music was supposedly designed to accompany athletic training regimens, GDR propaganda films, meditation exercises and a personal astronomy-themed project, among other dubious purposes. It maintains an unflaggingly upbeat pace, and taps into a nostalgia for the never-was in a way similar to Simon Stålenhag’s Tales from the Loop (2014, and, worth noting that Stålenhag has released four of his own albums of moody electronic music). The notion of the existence of some sort of secret music-based training program in the Eastern Bloc is a pure delight to me and just plausible enough that I am content to let the truth of it lie unpursued. The West had all sorts of rumors about what the Communists were up to during the Cold War. Let this story reside with alongside them, uninvestigated.

6.

There are scads more. The label Abstrakce Records has a series of split LPs called The Encyclopedia of Civilizations; the first is Egypt (2017), which is mysterious enough, but the second sees DSR Lines and Bitchin Bajas diving right into the legends of Atlantis (2018). The oldest example I’ve found of an explicit connection between the occult and electronic music is an album by electronic music pioneer Mort Garson called Black Mass (1971), released under the nom de plume Lucifer, which has track titles like “Exorcism” and “Solomon’s Ring.” He returned to similar fare with 1975’s The Unexplained, recorded as Ataraxia. Along similar lines, Michael Garrison’s In the Region of Sunreturn (1979) and Steve Roach’s Traveler (1983) get filed under New Age music, a fairly meaningless umbrella term with connections to a system of modern folklore that gets filed in the book store under the same, fairly meaningless umbrella term.

But why? What is it about ambient electronic music that makes it so well suited for soundtracks to the mystical, the spooky and the folkloric? I think a lot about The S from Hell (2010), the short documentary by Rodney Ascher about children who were terrified of the motion and synth accompaniment of the Screen Gems logo that came into use in 1964, following the credits of TV shows like The Monkees. In it, folks recount their fear of the logo along with the measures they would take to not see or hear it once their favorite show ended. It seems a supremely silly thing to be frightened of – it’s just eight notes, a little electronic trill.

I suspect the answer is because electronic music is, for all intents, actually unnatural. You can’t hear the natural thrumming of a Moog on a walk in the woods the way you can hear a clarinet when the wind hits the hollow of a tree the right way. Electronic music started development in earnest as a byproduct of the invention of the telephone and telegraph, when it was discovered that the electromagnetic currents of that technology could be manipulated to create predictable sounds (I should note, too, that during this period of the late 1800s, all manner of spiritualism and occultism were on the rise, and acolytes of the unseen were often just as interested in the miracles of modern technology as they were the spirit world, and history was repeating in the ‘60s and ‘70s in this regard). Before the Telharmonium’s invention in 1897, most human ears had never been touched by an electronic sound, and it wouldn’t be until the 1920s and the popularization of the Theremin that we, as a species, started to develop an aural vocabulary of the electronic. These sorts of sounds are commonplace now, but until recently, they were heard, on an instinctive level, as otherworldly. Why else, then, would Delia Ann Derbyshire’s electronic version of the Doctor Who theme (1963), realized at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, become so synonymous for audiences with that singular time-travelling alien who exists so wildly outside typical human experiences? (And at the same time, perhaps also seeding the ground for a British preoccupation with this sort of spooky electronica.) Why else do shrill synths so often accompany horror films? Peter Weir’s The Last Wave (1977) is a movie about Australians Aboriginal people and a looming apocalypse the derives its themes from some of the world’s oldest spiritual traditions, but it carries a score by Charles Wain that incorporates droning synths and manipulated didjeridu that could only be the product of 20th century technology. That seems combination seems ripe to clash, yet somehow, it is the perfect accompaniment.

Electronic music is thoroughly modern music. And the truth about the folklore that these sorts of projects score is that it’s thoroughly modern folklore. UFOs entered the collective consciousness in 1947. New Age spirituality is a reconfiguration of Western esotericism largely assembled in the ’50 and ’60 (partially in response to UFO-focused religious movements like the Aetherius Society). The Cold War “ended” in 1991, but the ripple effects continue to come in to the cultural shore like the tide, even the ones from fictional Olympic programs. The excavations of alternate British pasts that is going on with Ghost Box, and all these musical explorations, require a present to stand in and look back from. It may seem like nostalgia or anemoia, because we’re looking over our shoulders, but in the very definition of those words is the acknowledgement that what they seek is lost or non-existent. Perhaps we ascribe this feeling of longing to the past because it is safer or more comfortable than admitting this is how now feels.

———

Stu Horvath is the publisher of Unwinnable. He reads a lot. Follow him on Twitter @StuHorvath.