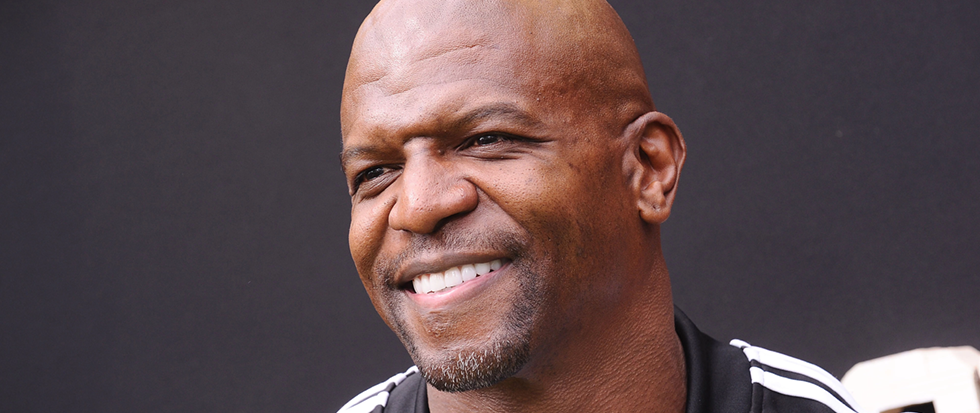

Terry Crews, Silence Breaker

It’s been a little over two months since The New York Times broke its story about Harvey Weinstein. And yet its already difficult to remember a time when my newsfeed wasn’t a stream of surfacing sexual assault allegations, firings, and suspensions seemingly unbound by industry. So when TIME Magazine announced its Person of the Year winner was the Silence Breakers – a group of individuals spurred by movements like #MeToo to speak out about their experience with sexual abuse – I was proud, but unsurprised. But when the cover started circulating, featuring trailblazers like Ashley Judd and Adama Iwu, I was shocked by the one I couldn’t find: Terry Crews.

The NFL player turned actor first spoke about the alleged sexual assault in October, inspired by the women confronting Weinstein. Crews claimed a Hollywood executive, later identified as Adam Venit, a talent agent for William Morris Endeavor, groped his crotch and made lude gestures at him at a party in 2016. Crews has since filed a sexual assault lawsuit against Venit, who also faced demotion and suspension without pay at WME. And while the TIME piece details this development in an aside with Crews’ picture, he is neither mentioned in the story’s body nor featured on the magazine’s front cover.

The latter omission is a huge missed opportunity for the feminist movement given its historical focus on white, cisgender women. While I applaud TIME for featuring a diverse group of women, the choice to include only women frames the discussion in a way that ignores many who are already struggling to speak out against the same crimes. Crew’s inclusion would have challenged the media’s traditional image of what a sexual assault victim looks like, and forced people to see the problem as a human issue rather than a woman’s issue.

Adult men statistically face less risk of sexual assault than women, true, but they are also far less likely to report instances when it happens to them. Their very definition of sexual assault can vary wildly from that of women; in cases of individuals with documented histories of sexual abuse, 16% of men considered themselves to be sexually abused compared to 64% of women. All of this becomes even more disturbing when you consider studies have found that, before their 18th birthday, one in six boys will face sexual abuse.

To be clear: this is not a competition about which victims do or don’t deserve to be recognized. Every single individual in that piece is incredibly brave for speaking out, and I’m proud that such a monumental issue is receiving this attention. At the same time, I can acknowledge the incredible impact this cover could have had for those who feel pressured into silence by a culture with toxic ideals of masculinity and ignored by a movement that advertises a goal of equality.

In another impactful blow, this image – a physically imposing Crews standing united in victimhood with women – would also directly contrast stereotypical portrayals of black men as ravagers of “(white) female virtue.”

While this practice has a history stemming back to the Reconstruction era, we can see its lingering affects in media today. Vogue came under heavy fire in 2008 for its cover featuring LeBron James, the magazine’s first to include an African American male. Critics called his bared-teeth expression “ape-like,” likening the image to a WWI propaganda poster of a menacing gorilla clutching a damsel at its side.

Such racist depictions have a bloody history. After the Civil War, the minstrel show’s submissive, laughable slave caricature was subverted by a vicious image of savagery, a reflection of white society’s own insecurities over increasingly influential political and social power for African Americans. Mobs fueled in equal parts by fear and a desire to preserve their cultural status used this stereotype as a justification for thousands of lynchings throughout the late 19th century into the 20th century.

For many, the hysteria over this myth never died down. In 2015, white supremacist Dylann Roof shouted “You rape our women, and you’re taking over our country, and you have to go” before killing nine African Americans in a South Carolina church according to a survivor of the shooting. Centuries of poisonous representation of black male bodies continues to threaten lives today, manifesting as the “thug” stereotype or the scientifically tested prejudice among some police officers to see black boys as older and less innocent than white boys.

Which is why a chance to show a black man in such a vulnerable role alongside women carries such weight. One magazine cover won’t singlehandedly overturn a history of systematic degradation, I realize that. But right now, there’s a small archive of famous images that feature black men as the abused rather than the abuser. Even adding to that by one would have been a move in the right direction.