The Visual Poetry of Film and Godhood

Ours is not the only reality.

Even the most basic understanding of quantum mechanics or Zen Buddhism can clue you into this particular truth: linear time is an illusion, everything that is possible and impossible already exists all around us, all of this has happened before; all of this will happen again, etc.

The Hindu creation myth posits that we are each of us expressions of a single self, pretending at being everything in some great drama. You, me, the screen you’re looking at, the car that just drove by, the meal you’re going to eat in four days, the mirror your neighbor broke when he was eleven–all of these things and everything are one.

So, that raises the question: why, in the Hindu case, would a grand energy-being (language doesn’t quite suffice here, but they call him Brahman), why would Brahman want to expand his energy into all the possible realities and pretend that he’s not himself.

The Hindu answer is Lila, the Sanskrit for play. He’s doing it for kicks. If that seems frivolous, let’s ask Alan Watts to ground the idea.

Imagine you could dream any dream you wanted every night. That you were in total control of the experience:

“You would have every kind of pleasure during your sleep. And after several nights of 75 years of total pleasure each you would say “Well that was pretty great”. But now let’s have a surprise, let’s have a dream which isn’t under control, where something is gonna happen to me that I don’t know what it’s gonna be.

And you would dig that and would come out of that and you would say “Wow that was a close shave, wasn’t it?”. Then you would get more and more adventurous and you would make further- and further-out gambles what you would dream. And finally, you would dream where you are now. You would dream the dream of living the life that you are actually living today.

That would be within the infinite multiplicity of choices you would have. Of playing that you weren’t god, because the whole nature of the godhead, according to this idea, is to play that he is not.”

Got it? Good. Let’s figure out what the hell this has to do with movies.

The vast majority of films made today, both in independent cinema and within the studio system, are narrative films. Now, some of you just stopped and tried to think of a single film you’ve seen that wasn’t essentially narrative. If you can’t think of one, don’t feel bad; narrative cinema is the norm. I’ll give you the most easily identifiable example form the last thirty years: The Revenant.

Iñárritu and his posse took some flack in critical circles for the simplicity of The Revenant’s story, as though the story really mattered to the filmmakers. I’m much more comfortable with the argument that Iñárritu didn’t denude his film enough of its attachment to certain conventions of narrative cinema to earn the praise it received as a work of visual poetry.

Terrance Malick, whatever you may think about his films, is undeniably a visual poet. He willfully abandons narrative structure to provide you with a landscape of signs and signifiers in which you may swim and free-associate to your heart’s content.

Why the comparison to poetry to begin with? Well, poetry went through a transformation in the last couple of centuries not unlike the one that cinema, frankly, deserves.

Up until the heavy hitters of the lyrical style like Rimbaud, Keats, Whitman and Baudelaire came along, poetry enjoyed a tremendous variety of popular styles. Reaching back to its origins, of course, you have the first human narratives, epic poems committed to memory and enhanced by the poets and singers of the day.

There were later, in addition to narrative poetry, political manifestos writ in verse, plays, dialogues, eclogues, opinion pieces–any idea had as an optional outlet for its expression some form of poetic verse.

As the 19th century came to a close, however, the popularity of lyrical poetry began to peak, while all other poetic styles began their sharp, steady decline.

By the time William Carlos Williams, Robert Lowell, Hart Crane and that lot inherited the mantle, there was next to nothing left of the other styles. Lyrical poetry had won the day, or what was left of it. I would argue that the institution of poetry’s blind and exclusive investment in this often esoteric style greatly precipitated its demise.

The film industry won’t face quite the same problem, as it’s a more elaborate and well-built financial machine than poetry ever was. It will have to adapt to new technology, but it’ll thrive financially, one way or another.

At its outset during the turn of the 20th century, film was employed to record the narrative structure of the theatre. Actors turned out toward the camera as though it was the lip of a stage, and they often shared the frame with one another. As more visionary directors employed close-up and montage to tell their stories by employing more and more visual information, the art form evolved into something entirely unique.

Those daring directors of the 20s, like Sergei Eisenstein and Luis Buñuel gave way to the American auteurs of the 40s and 50s, filmmakers like Orson Wells and Hitchcock in his heyday. These men employed their visuals to relay very specific visual information to the audience of which there was little room for interpretation. They were more like serial novelists than poets, more Dickens than Dickenson.

Elsewhere in the world, cinema was experiencing the great revolutionary movements in France, Italy and Japan. Truffaut, Godard, Fellini, Antonioni, Mizoguchi and Shinoda, busily made their marks with a style of filmmaking that was uniquely disinterested with plot. Even Kurosawa made films that explored the landscapes of dream and inference before concerning themselves with the weight of a story.

None of this is to disparage the narrative style, mind you, or to say that the narrative and the lyric are mutually exclusive. As modern auteurs have begun to incorporate these styles form their predecessors, we’ve seen some of the best movies ever made resulting from a balance between the two.

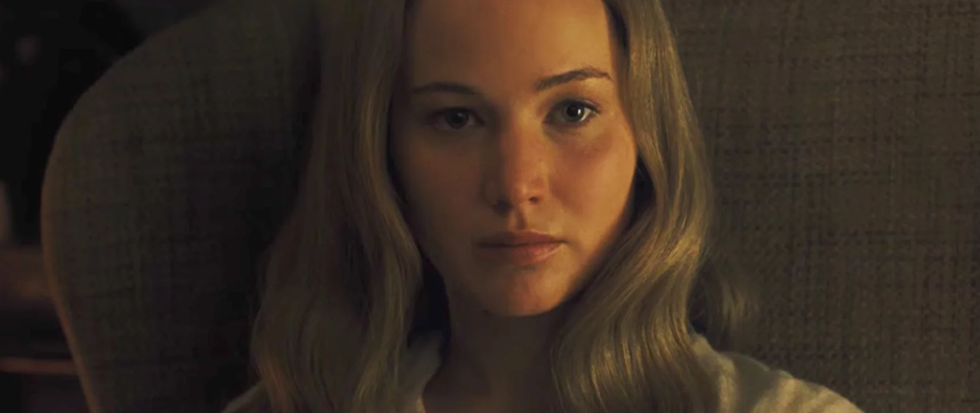

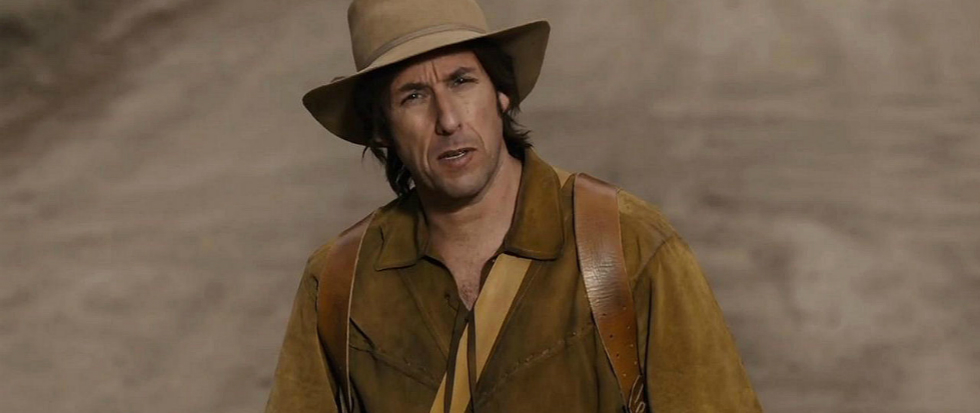

Iñárritu, P.T. Anderson, and Mr. Malick make a few recent examples, but those men would all exist even further on the outskirts of cinema than they already do if it weren’t for the star power of their casts.

These types of films are also few and far between, as the industry is almost unconditionally married to the narrative style, much in the same way that modern English verse married itself so stubbornly to the lyric.

One of the reasons The Revenant did so well (526 million), in addition to the Oscar buzz and the talented, popular cast, is that it spent the majority of its time stealing shots form one of the greatest lyrical stylists in film history: Andrei Tarkovsky, a director whose work reaches its audiences in that place where Brahman lives.

Tarkovsky was an unapologetic lyricist. His films delve with unbelievable patience into thematic imagery, casually entering dreams and memories, lingering on simple, allegorical images.

Remember the jellyfish at the beginning of Birdman? I ask people about this all the time and next to no one ever remembers the damn jellyfish. How about Hugh Glass’s flashback to the times when his wife and son were both alive? The editing, the composition, the pacing–all straight Tarkovsky.

And those are some of the most powerful and important parts of The Revenant, but, like the jellyfish in Birdman, it isn’t important that you remember them. What’s important is that, by the time Riggan Thomson relays the story of being stung by a swarm of jellyfish while trying to drown himself in the ocean, we have the image floating around our subconscious.

These dreams and memories, these semiotic moments that touch us in ways we can’t quite codify, are the stuff of our collective, waking dream.

Ingmar Bergman says this about Tarkovsky: “Tarkovsky for me is the greatest, the one who invented a new language, true to the nature of film, as it captures life as a reflection, life as a dream.”

When I first read that quote, I immediately asked: Why film? Why do movies mean so much to us in the first place?

Here’s what I think: film hits us hard in our two most powerful sense receptors, our eyes and our ears. What we see and hear on film is, essentially, another reality. It’s quite like this one, but it has its specific differences (555 phone numbers, for example).

When we watch a film, we are literally peeking into a parallel universe, taking a controlled glimpse at a space and time existing in concert with our own on some other plane. And, in contacting another reality, even for a moment, we are unconsciously reminded that we are, as the Hindu’s and the physicists alike would tell us, all the same one thing branching out for the hell of it.

The more visually metaphorical a film can be, the closer it takes us into the realm of the subconscious, which is where the knowledge of the Brahman

resides with hidden clarity.

The film as alternate reality idea also explains why celebrities exist at all. If you really think about it, a reality I watch studios rely on the proven box office numbers of certain actors to help sell new projects is no more ludicrous than a world in which they might never want to reuse an actor simply because he or she already played an iconic part. In fact, this has happened plenty of times in the industry (Elaine!).

The film as alternate reality idea also explains why celebrities exist at all. If you really think about it, a reality I watch studios rely on the proven box office numbers of certain actors to help sell new projects is no more ludicrous than a world in which they might never want to reuse an actor simply because he or she already played an iconic part. In fact, this has happened plenty of times in the industry (Elaine!).

We prefer to see the same person playing so many different roles, in part, because it accents the knowledge that we’re experiencing another reality: today Bradd Pitt is a zombie exterminator, yesterday he was a vampire! Superhero movies double-down on this prospect, reusing top talent to give more credibility to an increasingly absurd and elaborate alternate reality.

Most celebrity vehicles, and all of the superhero movies, however, are strictly narrative. Perhaps their celebrity status and more potently absurd premises do enough to reconnect us with that great universal origin, with Brahman, that we don’t need to get into the lyrical.

But if Tarkovsky’s and other lyrical auteurs are renowned for fluently speak the language of dreams, and if we spend a third of our lives asleep, shouldn’t more filmmakers at least dabble in this language?

I guess the problem is that it’s a tough language to speak. It requires tremendous creative imagination, deep emotional and intellectual intelligence, and giant swinging balls. If there’s one thing Hollywood doesn’t have enough of, it’s a tremendous creative imagination, deep emotional and intellectual intelligence, and giant swinging balls.

Thus, it falls to independent cinema to take up the mantle of the lyrical cinema, to tell by a higher art the great story of mankind.

When our escape from this reality can remind us what we all come from, that we all are one being, then that art is a more direct line to the ultimate truth about existence, and watching that is like coming home.