The Devil’s Disguises

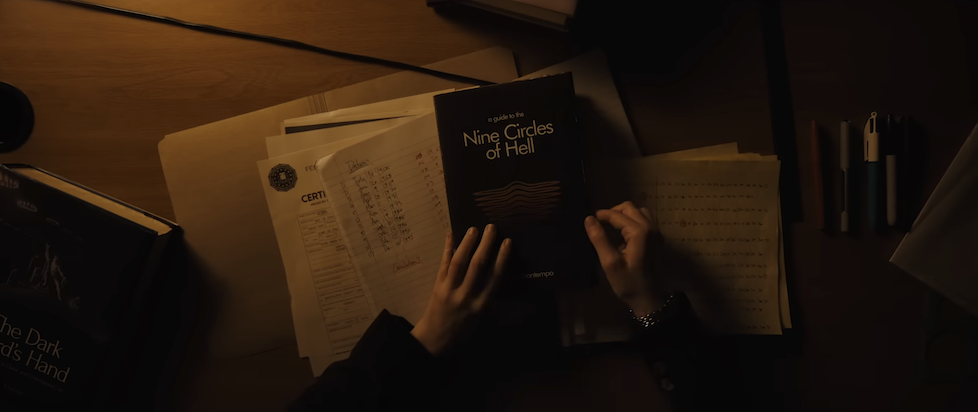

Oz Perkins knows The Devil. The director’s filmography, stretching back to 2015 with his directorial debut The Blackcoat’s Daughter, is rife with haunting religious dread. It’s a wonder then how a director who came out swinging with a tale of grief and what fills the hole that loss leaves behind could somehow fumble so hard with Satan’s presence in his most recent feature, Longlegs.

To bring The Devil into the picture is to inflict a rigid structure on the work. Many audiences come equipped with an understanding of how the apocryphal forces of Hell and Satan operate, but they’re also weighed down with specific expectations. This is why so many stories that introduce these concepts lean heavily into the world of metaphor. When it’s not THE Devil, but rather a personal devil, it becomes a reflection of the character(s)’s temptations, desires, and failures. It’s critical that, in a story that attempts to seriously engage with specific themes, a distinction be made lest it unintentionally imply that the Christian concept of sin is real. If hell is real, does true sin exist? Is The Church’s interpretation of Christian morality just correct? This is where Longlegs falters – it can be argued that the film’s depiction of Satan is an investigation of agency. It’s no coincidence that the titular character (played by Nicholas Cage) is a dollmaker, while being a sort of “puppet” for The Devil himself. It is unfortunate then, that the film falls apart in the last act in order to shuffle Cage’s character offstage, introduce yet another layer of manipulation, and to include a conspiratorial twist involving the main character’s mother, and supernatural dolls that might contain souls. It all makes a certain kind of sense, but the answers provided weaken the work rather than strengthen it, and fail to come up with anything interesting to say and a whole lot of wasted effort.

By failing to engage with its own imagery in a real way, it instead lends legitimacy to the Satanic Panic. Worse yet, giving Cage’s character an obsession with glam rock so intense as to mold himself in its aesthetic trappings (his appearance implies several feminizing cosmetic surgeries, he sings poorly along with 70s rock n roll, and his living spaces are covered with posters of Lou Reed) wavers on the line of bowing to conservative hokum about degeneracy at best, and commits a deep homophobia at worst. The presence of the character is very obviously an homage to Buffalo Bill of Silence of the Lambs, but that carries its own problematic weight. To pluck Buffalo Bill and place him in a world where Hell is real and The Devil can force others to do his bidding is to imply these cultural movements (helmed mostly by queer people) have a dark power behind them, that they truly are the spaces of evil that conservatives of the era claimed they were. I don’t know Perkins’ politics and I am a firm believer of attributing missteps like these to ignorance or sloppy work rather than malice, but it makes for a disquieting watch. This failure to reckon with the film’s inspirations mean the same trans and queerphobic underpinnings return thirty years later, way past a time in which everyone should know better. The film commits the sin of borrowing without interrogation, a quote without discussion.

These bullets aren’t difficult to dodge, either – Arkasha Stevenson made her feature film debut with a prequel to the long running Omen series, The First Omen. I admit that upon hearing about this movie I rolled my eyes and planned on skipping it until critic and author Gretchen Felker-Martin gave a glowing review, and I’m glad she did. The First Omen taps into what makes hell so scary – sure, there are supernatural forces at work, but it’s all so human. The villains of The First Omen are the leaders of the church itself, a crumbling empire so fearful of its disintegrating power that it must invent a villain to win the loyalty of nonbelievers through fear and desperation. The antichrist, and the Church that birthed him, are both envoys of domination and subjugation, specifically over sexuality and women’s bodily autonomy.

What greater way to interrogate the themes of loss of agency and autonomy than to implicate the viewer themselves? Indika, released this year, is a narrative adventure game where the player controls novice nun Indika, a young woman who has taken up residency in a convent in a fictionalized, steampunk alt-history Eastern Europe. Her reasons for this are revealed over the course of the game – her father murdered her lover, and out of fear, she has figuratively barricaded herself within the walls of a convent. Unfortunately, her only constant companion is what is heavily implied to be The Devil. Acting partly as a narrator, he’s in her ear throughout the adventure, commentating, criticizing, and even tempting her towards “unholy” acts. During Indika’s runtime, there’s much philosophizing about the nature of choice, whether one can truly be free, and what it means to take hold of one’s future. A scene towards the end insinuates that it is not Indika that the player is controlling, but rather Satan influencing her actions. It’s a marvelous twist, seamlessly bringing theme and gameplay into perfect synthesis. Indika’s failure to grapple with her past leads her straight into the arms of another controlling force, another dead end that will leave her without the courage to make choices that are truly her own.

Despite these works’ success in their interrogations of The Devil, I keep finding myself drawn back to Longlegs. It’s such a terrifying thought, to view personal agency as a matryoshka doll of masters, to imagine the strings that compel our movements extending so far they find themselves in the realm of the supernatural. What takes that a step beyond is when that supernatural force, though so far removed, still reflects a distorted human desire. Longlegs fumbles at the last moment, failing to let us see ourselves in its Devil.

———

Ryan is a Brooklyn-based enthusiast who spends almost as much time playing games as he does thinking about them. You can find more of his work at criticalconstruct.substack.com or @_ryansw on Twitter.