Militarie Gun Rings the Bell

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #172. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Ruminations on the power of the riff.

———

I almost couldn’t believe it when I first heard Militarie Gun on a Taco Bell commercial. I wasn’t paying attention until I heard something that sounded vaguely familiar come from the TV and my wife asked, “What’s this hardcore song doing on this ad?” It took a moment for my brain to register that I wasn’t losing my mind and were, in fact, hearing the band’s single “Do It Faster” being used to sell fast food, with vocalist Ian Shelton’s trademark bark blasting through the speakers while images from a house party flashed across the screen.

Whoever pitched this campaign to Taco Bell knows exactly what they’re doing. Militarie Gun aren’t the first emerging punk band to be included as part of the chain’s Feed the Beat campaign, which sponsors artists with free food on the road, and in the last year has also featured Turnstile, White Reaper and Scowl in national TV spots. If the goal was to find underground bands on the cusp of a mainstream breakout, then they’re building an incredible track record.

When I mentioned the ad on Threads (it feels weird to say Threads and not Twitter), a friend responded that there was once a time where they would have disowned a band like Militarie Gun for being in a commercial. While I was spending all my brain power trying to process how the hell these commercials were even getting made, I hadn’t considered the fact that I would have reacted the same way when I was younger. They wouldn’t have felt like they were “mine” anymore, having traded their artistic ideals for the shallow rewards of capitalism, and thus would have to be branded sellouts.

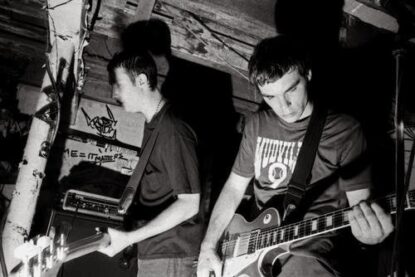

In a November issue of his recently revived zine Antimatter, writer and Texas is the Reason guitarist Norman Brannon wrote about how the pressure of being called a sellout led his band (and several others) to break up right when they were on the verge of major label success back in the mid-1990s. There was a collective sense that punk and hardcore bands belonged to the community that had cultivated spaces for them to grow, and leaving the world of basement shows and independent labels was an unforgivable betrayal. The piece called to mind former VICE editor Dan Ozzi’s Sellout (which is an excellent read), a tome that catalogs several stories from bands that found themselves in similar situations.

The concept of selling out is mostly silly for reasons that most grown adults can see. But when you’re young and this music is what your life is oriented around, these are the things that matter to you. For bands that are used to playing small venues on self-funded tours in vans, there are risks to accepting offers from corporations and major labels, and there are also ethical and existential implications for shaking hands with the devil so to speak. But sometimes what holds punk and hardcore bands back isn’t just actual concerns about keeping creative control and staying true to their roots, but simply worrying about what their peers would think if they made the leap.

As a case in point, Brannon writes that Texas is the Reason thought no one would care about them if they signed to a major label when they had the chance. That thought was proven incorrect when they reunited years later and played to thousands of people in New York City, most of whom never got to see them and had only heard the band after they split up. In an alternate universe, they might have been as big as Weezer or Jimmy Eat World. The songs were good enough. But other internal and external forces held them back.

Forget the hypocrisy inherent in how either my friend or myself would have decided what forms of “selling out” were or weren’t acceptable (it’s helpful to understand that both of us come from a generation that was introduced to punk rock in part through the early Tony Hawk Pro Skater series of videogames, which weren’t exactly scrappy indie titles). My friend was right. I can 100% see a younger version of myself throwing a crunchwrap supreme on the ground and declaring Militarie Gun dead to the world (or at least dead to myself). At the very least, that commercial would have forced me into an uncomfortable compromise on the loose collection of beliefs that I would have called my “ethics,” and if I kept listening to them, I’d at least have to complain about how their old stuff was better.

Looking back, I can’t help but think that so much of the music I grew up loving was held back because of this attitude. I used to spend hours reading the review sections of music magazines, digging through the “thank you” sections of CD liner notes, and going to shows to see bands I’d never heard before, all in the hopes of finding the next band that would show me something I’d never heard before. When you have to go digging to find the stuff you like, every band you “discover” feels like they’re “yours.” Any time one of those bands escapes their underground scene, it feels like theft.

I want honest music to be given the opportunity to grow and find new audiences in a social and economic environment that’s doing everything it can to make survival impossible for artists. If we need Taco Bell of all places to help tip the scales in favor of artists while buying themselves relatively cheap PR and backing tracks for TV spots, then that’s telling of a broader problem, but frankly I’m glad bands today aren’t afraid to take that money. I’d like to live in a world where the music I love doesn’t need corporations for distribution. Until we create sustainable infrastructure for independent music to thrive, Taco Bell might not be the hero we want, but they’re probably the weird corporate benefactor we deserve.

———

Ben Sailer is a writer based out of Fargo, ND, where he survives the cold with his wife and dog. His writing also regularly appears in New Noise Magazine.