What The Good Place says about game design

The other shoe finally dropped on The Good Place. Finally, after nearly three seasons, the full horror of its premise alluded to from the first episode has been explicitly laid out: We’re all screwed.

If you haven’t watched the show and plan to at some point, this is probably where you should stop reading, because I find that it’s one of the few stories that are actually enhanced by keeping some elements of their plots a surprise. Unfortunately, I can’t really avoid spoiling some of the major details if I want to talk about what I’m aiming to talk about, which is how The Good Place is a perfect illustration of what we actually mean by politics in games. So we just have to go for it.

Still with me? OK, good.

The Good Place’s central conceit is that there is a universal scoring system by which people are judged, and their scores determine whether they get into Heaven or Hell. From the beginning, it should be obvious just how terrifying this idea should be: if petty things like enjoying pineapple on pizza are enough to earn you eternal damnation, who the fuck is assigning the points, and would you really trust immortal beings that judged anyone that way?

For the last three seasons our main cast has been preoccupied with earning a spot in the titular Good Place, but in the most recent episodes, we’ve learned this is effectively futile. No one, not one single human on the surface of the Earth, has made it into the Good Place in over 500 years. The reason for it is basically “no ethical consumption under capitalism”: every person’s actions are so complicated by the exploitative systems in which we work and live that it is impossible for a human to earn enough points anymore.

What do these choices say about what you value and whom you wish to reward?

What’s the solution? Up to now, Michael (Ted Danson), a demon turned benevolent caretaker of our four doomed heroes, has fixated on the idea that the system is rigged and if he can only rectify it from within, everything will be fine. But it’s not technically rigged – no one’s thumb is on the scale, it’s just that humans have started playing the game in a way the system hadn’t intended, and to which it (apparently) cannot adapt.

The Good Place scares the crap out of me on a regular basis because of stuff like this, but I do think it’s a useful illustration of what we mean when we say all systems reflect the biases and points of view of their creators.

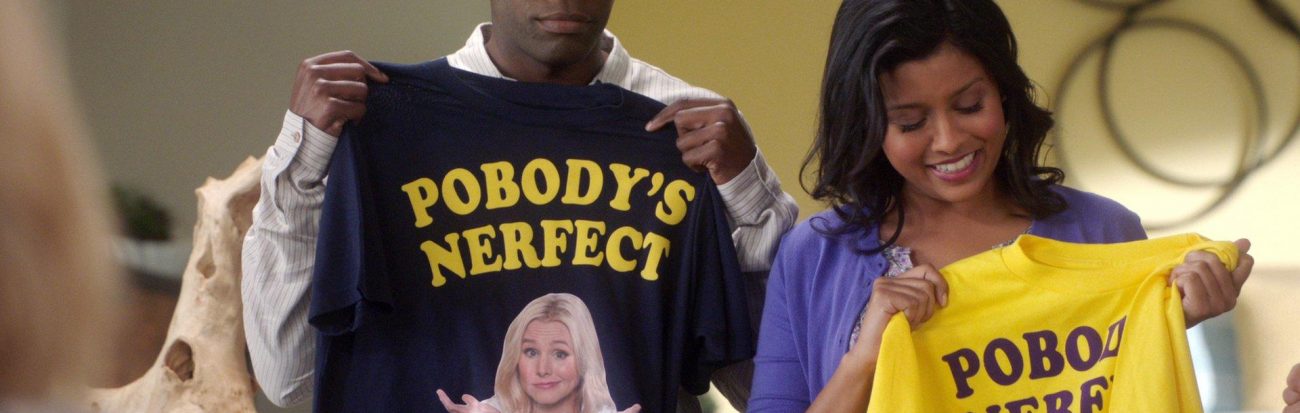

Many of the things the show treats as mortal sins are “trashy” low-cultural stuff strongly associated (rightly or wrongly) with lower economic classes: processed foods, mainstream music, screaming sports fanaticism, poor public manners. Why are these things bad? Because the writers found it funny, yes, because every last one of us has at some point been annoyed or grossed out at someone and wished they experienced real consequences for their behavior — but supposing The Good Place’s morality system were real, that’s a lot of people getting sent to hell for the crime of not growing up with “acceptable” tastes or access to the “right” resources. I mean, are we under any illusions that Eleanor (Kristen Bell) and Jason (Manny Jacinto) didn’t get where they are largely because they grew up in broken homes without money or good role models?

If you’re a game designer making The Good Place: The Game, what do these choices say about what you value and whom you wish to reward? What is your ideal player supposed to look like? How many of those ideal players do you expect to find? Is there really any good reason why your game can’t be more accessible?

If you’ve run a game for eons and all of a sudden not a single player was making it to the end goal, is that your fault or theirs?

Anyway, I write these things a week in advance so it’s possible by the time this article runs, the new episode will crush everything I’ve written here into meaninglessness. But I haven’t stopped thinking about The Good Place once since I started watching it, and I believe that’s because it’s one of those rare pieces of work that really looks hard at its own premise and questions where its assumptions are coming from. And I think that’s a good approach to take for anything we create, honestly.