The Best Books of 2020

As is tradition around the Books end of things here, the past year was spent mostly catching up on pre-2020 books. For Levi, it was the entire Earthsea series, save the final story, which his heart cannot quite bear just yet. For Noah, it was the Patternist series, which felt apropos for most of the political climate of 2020.

It’s been a year of burdens, and we’re not sure that 2021 will be much better for folks. But we have faith that books will continue to inspire, instruct, entertain, baffle, and illuminate our lives and the interestingly cursed times that we find ourselves embroiled in.

And if nothing else, a new year means a new start, a time to catch up on all the books you’ve missed. Why not start with these heavy-hitters from the good Unwinnablers who are much more timely than us, the book section editors? We take all kinds here, and hopefully you do as well.

– Levi Rubeck and Noah Springer, Curators

Whiteout Conditions, by Tariq Shah

Whiteout Conditions, by Tariq Shah

I love the opening sentence to Tariq Shah’s debut novel Whiteout Conditions. “With the last of my loved ones now long dead, I find funerals kind of fun.” It’s sardonic, bitingly honest and immediately suggestive of the type of person Ant – the narrator of the story – is: destructively avoidant.

This brisk novel centers around a trip back to Ant’s hometown and all of the complications that come with connecting with old friends long absent. I admire the clarity Shah’s prose has in showing the often fraught nature of communication in male friendships. Conversations between Ant and his friend Vince are cloaked in half-truths, anger and indifference. Just as the two are at the precipice of saying what they need to say, the masks come out.

Much like the title suggests, the interactions between the characters capture the feeling of driving through whiteout conditions. The truths that seem to be plainly in view, morph and change at a moment’s notice. Despite Whiteout Conditions’ short length, the lyricality through which Shah draws his characters suggests the depths lurking within them. By the end, everything and nothing seems to be resolved for Ant. And to me, you can’t get much truer to life than that.

– Phillip Russell

The Sprawl, by Jason Diamond

The Sprawl, by Jason Diamond

Everyone knows the suburbs suck. Once seen as the utopian future of city planning, they soon became synonymous with sameness and quiet desperation. Typified by characterless subdivisions and shopping districts arranged with all the thoughtfulness of a lazy kid copying and pasting their way through a round of Sim City, if you’ve seen one, then it’s safe to say you’ve seen them all. These are the places your favorite artists escaped, and if you heeded the warnings in their works, then you probably did too (if you weren’t fortunate enough to grow up outside their suffocating boundaries).

But what if these stereotypical views are too narrow and there’s more beneath the surface of suburbia’s superficial sheen? That’s the question author Jason Diamond explores in The Sprawl, seeking not to defend nor dismiss their existence, but to better understand exactly how they’ve shaped culture and society. If that sounds like an oxymoron, then that’s why this book needed to be written. The suburbs are fucking weird, sure, but there’s much more to them than congestion and chain restaurants.

Conversations around suburban and urban divides often flatten places into stereotypical pastiches that erase everything unique about the people living in them. Diamond skips past judgement and instead brings us closer to understanding how the broken promises of suburban living have driven all kinds of societal impacts beyond being boring and ironically inconvenient. The Sprawl is an examination of politics, economics and culture, viewed through a lens that is everywhere yet rarely seen in full.

– Ben Sailer

Heaven Official’s Blessing, by Mo Xiang Tong Xiu

Heaven Official’s Blessing, by Mo Xiang Tong Xiu

It’s hard to explain to normal people that the best book I read this year was a Chinese boys love web-novel that finished in 2018 called Heaven Official’s Blessing. Recommending this book to others with the pitch that it’s a gay, Disney-esque, PG-13 romance between a handsome prince who pleased the gods and the devilish ghost king who loves him, that yes you do have to read it in translation and no, there’s no official copy, that it is in fact 1.2 million words and 244 chapters (252 with the bonus chapters) and that yes, it is actually the tightest plotting and most satisfying story I’ve seen in media since Full Metal Alchemist: Brotherhood – well, it’s not an easy sell. It helps if you can start someone watching the animation (helpfully streamable on Funimation) and tell them that they’re filming a live-action drama in 2021.

But to explain that a novel this long is actually so well plotted, funny and has not only the best main couple who invented love but also incredible side characters? Let me sell it to you like an Archive of Our Own story: Heaven’s Official Blessing features childhood friends turned lovers; a god/demon romance lasting over 800 years which could technically be a slowburn except the main couple take each other’s hands in episode one and never stop trusting each other.

Xie Lian, the main character, is the Flower Crown Martial God, the prince who pleased the gods, who has fallen from the heavens twice and become the God of Misfortune who ascends to heaven and is sent to solve ghostly mysteries by the Emperor of Heaven. He meets up with the mysterious San Lang, the supremely powerful King of Ghosts Hua Cheng, who all the gods are afraid of. The story spans from haunted temples where brides are being kidnapped and killed to fights on a crumbling bridge over an active volcano, with plot points that include giant sea monsters, plagues that wipe out entire kingdoms, magical anthropomorphic scarves, a casino heist, transforming robots and overthrowing God.

If you want to read a book that has everything and does it perfectly, read Heaven Official’s Blessing. And the few normal friends I’ve convinced to read it? Every one of them has fallen in love with it.

– ailuridae (via Gingy Gibson, thanks Gingy!)

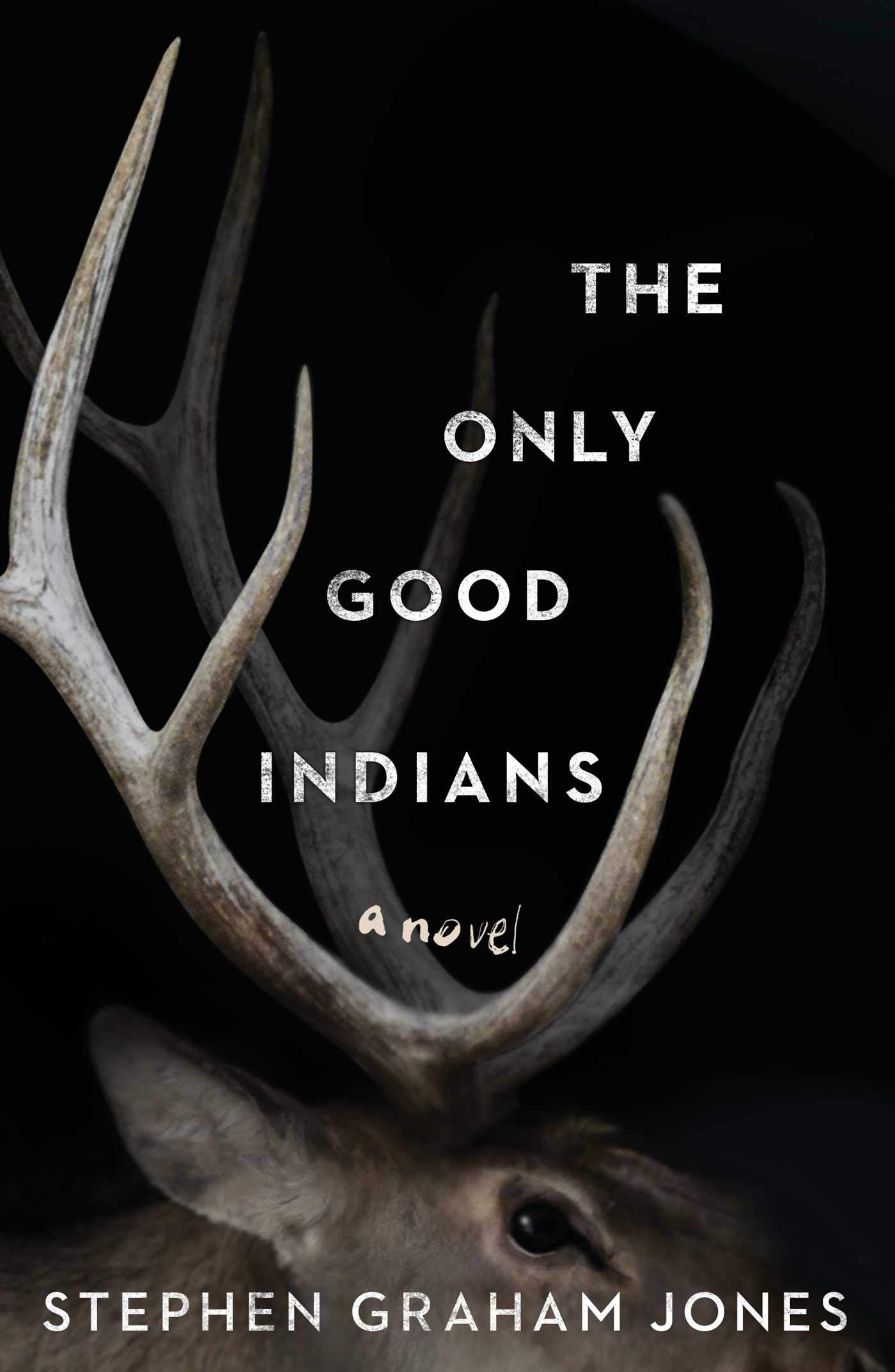

The Only Good Indians, by Stephen Graham Jones

The Only Good Indians, by Stephen Graham Jones

When it comes to horror, I have a pretty high tolerance. You might look at all the dark and gruesome stuff I stick in my brain and conclude I am jaded. That’s probably a reasonable assessment.

I had to put down The Only Good Indians three times to take a break and collect myself. The first time was the longest – a bit more than a month. The book, with its haunting cover, sat on my nightstand. I’d look at it, hand out to crack it open again, then I’d remember how it crept inside my brain the way no other horror story ever has, at least not that I can recall. Then my hand would lower, I’d shake my head and move on to something else. A whole month it took me to work up the nerve to get back into that book. And when I did, it slapped me around some more for my trouble.

It isn’t even the horror that knocked me for a loop, really, so much as the unfairness. Everything in the novel is slanted, permeated with a lack of justice, all the way down to some distant, cursed substrate. For all their faults, it is unfair what happens to the men and women who die during the course of the tale. It is unfair what happens to the elk and the dogs. It is unfair what happened to the Blackfeet tribe in the first place, back when white people colonized their land and subjugated them, and right now, too, when modern American life and some notion of the a traditional one clash in such a way as to keep the boot pressed firmly down. In a year broadly characterized by a perception of unfairness and unravelling, it is hard to read a book like this, that confirms that just about everything is fucked up and probably not going to get better. But just because it is hard, doesn’t mean it isn’t worth doing.

– Stu Horvath

The Relentless Moon, by Mary Robinette Kowal

The Relentless Moon, by Mary Robinette Kowal

The latest book in Mary Robinetter Kowal’s Lady Astronaut series, The Relentless Moon is a disaster tale wrapped in a spy thriller and planted firmly in lunar soil. A handful of years after the meteor strike which doomed life on Earth to slow extinction, Nicole Wargin, astronaut and ex-spy, finds herself facing a conspiracy to both destroy the lunar colony she’s stationed at and discredit her politician husband back home.

Kowal’s alternate history of the mid-20th century has always been a meticulously-researched vision of a world choking in prejudice while trying to rise above its own extinction, but the close confines of the lunar colony – and the horrors of the polio outbreak which further complicates the plot – emphasize the parallels to our current existence. The joy of watching competent, educated men and women working together to achieve things previously thought beyond the reach of humankind still seeps through, but there’s a desperation too, of the crushing inequality of it all.

Even if humanity can find a new home beyond the bounds of our rock, there will always be those left behind; The Relentless Moon has judgment aplenty for climate change deniers and anti-vaccination sentiment, but it also seeks to understand the desperation that would drive people to cling on to outdated beliefs and commit terrible acts. And while it may not be able to fully reconcile the hope provided by its scientific vision with the pain of those abandoned, it at least attempts to imagine a future where that seems possible.

– Rob Haines

Everyone on the Moon is Essential Personnel, by Julian K. Jarboe

Everyone on the Moon is Essential Personnel, by Julian K. Jarboe

I picked up Julian K. Jarboe’s collection of short stories for two reasons: first, a friend posted a one line review that read “I AM A BEAUTIFUL BUG!” and second, the book was described by the author as “body-horror fairy tales and mid-apocalyptic Catholic cyberpunk.” I don’t really know what those words mean together, but they create a delightful word salad in my brain, and reading Everyone on the Moon is Essential Personnel, they honestly make sense. Not in any way I can actually articulate, mind you. But they make sense. It’s like the moment in They Live when Rowdy Roddy Piper puts on a pair of shades and sees the world as it really is, but in this case it’s “queer fabulism.” You’ve gotta read the book to see what I’m seeing.

Like, I could tell you about how there’s this short story about menstruation, where instead of blood the character produces tools, and everyone around them is encouraging the act; isn’t it so useful, the tools that they’re producing. But the person doesn’t want the tools. The story is the perfect intersection of body horror and the desolation of gender, and it’s in this book. Which you should read.

– Amanda Hudgins

BBC: The Myth of a Public Service, by Tom Mills

BBC: The Myth of a Public Service, by Tom Mills

BBC: The Myth of a Public Service provides an easy-to-read potted history of the BBC and its relationship with the state. The book is very easy to read and skillfully complicates a lot of the prevailing narratives about the BBC and its supposed independence.

It probably seems a little navel-gazey for one of Unwinnable’s Brits to talk about a book related to British journalism, but there’s more to it than that.

Tom Mills gives some crucial analysis into the role of the media that could easily be applied beyond Britain. He talks insightfully about how political journalism, now more than ever, tends to be more of a display for the court than a source of substantive critique.

Democracy dies in darkness. But it also dies when it’s controlled by billionaires and aristocrats preserving their own interests. This book is a powerful tool in analyzing that system as creators/readers so we can fight for something better.

– Oluwatayo Adewole

You can find a full list of these books (minus Heaven Official’s Blessing) on Bookshop. This is an affiliate link.