Attack, Defend, Follow

I’m trying something different. Since 2016 (or maybe 2017, because I think it was Volition’s Agents of Mayhem that really broke me), all of my writing has been similarly premeditated. The approach has been to a) attempt to excavate, extrapolate and put into words the abstract characteristics which are present in all videogames, or somehow indelible from videogames’ spiritual being, and to try to achieve this by b) writing primarily about what I perceive as videogames’ inherently carcinogenic properties, the ways that, either deliberately or owing to intrenchable, decades-old habits, the design of videogames and the effects of that design variously harms players’ ability to perceive reality; how games stunt our soul growth.

But what I want to attempt, at least in this column in the near future, is to illustrate methods by which I believe videogames may be awakened from the nightmare of their nature. I want to ventilate what I believe are the possible, higher qualities of games and of game making principles, and provide examples of where I feel that, in contradiction to contemporaneous rubrics and standards of virtue, game makers have created visions of a greater videogame language. There are ideas about what videogames should be, and what videogame mechanics should be, and what videogame aesthetics should be. Those ideas all need to be obliterated. After that obliteration, we can reconstitute a more meaningful videogame.

There is a principle which suggests that controls – as in, the literal controls of a videogame – and the mechanics that they operate ought to provide as much interactivity, functionality, flexibility, tactility and versatility as is possible. A “good videogame” is a videogame that “feels” good to play, one where the inputs are intuitive and permit the player a high level of control over the game and their own in-game performance. Accordingly, a “good” videogame is also one where the mechanics and the actions available to the player, as operated by their controls, allow for a range of expressions that are consistent with genre: A shooting game should allow you to shoot, move, run, take cover, reload, change weapons, and so on with a considerable degree of lucidity.

There may be permutations on the methods by which these actions are executed. Gears of War’s active reload system is a useful example. In the mechanical and control-functional lingua franca of shooting games, reloading your weapon requires a single button press, but in Gears of War, while your character is reloading his weapon, you have the option to press the “reload” button a second time, and if you do it in rhythm with an on-screen meter, your character will reload his gun more quickly. In this moment, Gears of War’s mechanical and control-functional language becomes more subjective and esoteric. In contradicting the principles of the operative, utilitarian shooting game mechanical language, Gears of War suddenly invites not only a different experience in terms of playing, but a different experience in terms of feeling.

But this mechanical flourish in Gears of War is reflective of another principle, the annihilation of which must be achieved to discover a more meaningful type of videogame: the idea that giving the player more that they can control (in this case, control over the nuance of reloading a gun) is synonymous with creating more potential for meaning. The opposite principle, which says that the volume of a game’s subjective meaning gets louder when you limit (perhaps down to a single mechanic) the player’s means of interaction, also needs to go. I don’t believe that games like Gone Home or Dear Esther are inherently, formally, more able to coherently effect a subjective meaning than games that allow for considerably higher quantities of player interaction.

And so potentially more engaging, or redolent, or at least, in the most basic sense, interesting, given that its a comparatively underexplored concept, is a game that provides the player with control, interactivity, and functionality (and does not limit these in a way that is obvious, so obvious that the limitation becomes the main aspect of the game that we are occupied with noticing) but also, via that diverse interactivity and functionality, impresses something subjective upon the player. We’re accustomed to the idea that mechanical range and functional agency allow, and should allow, for extrapolation of the player, and the player’s behaviors, and the player’s desires, and the player’s personality. Giving people literal, functional control over games has become a synonym for giving them control over the games’ meanings – if we, as the game-maker, want to protect the game’s meaning, we need to similarly, perhaps with great surgery, limit the player’s control. There are games however where the controls and mechanics allow for an expansive range of player action, and in that system of controls and mechanics there is still detectable prescribed meaning and game-maker subjectivity. There are games where the player can exercise an enormous amount of influence over the game, and in exercising that influence also contributes to emphasizing and effectuating the game’s subjective thematic assertions.

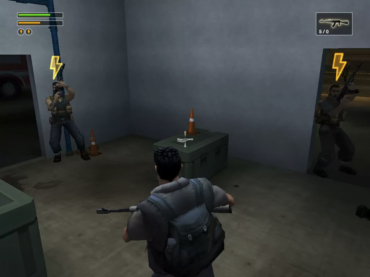

IO Interactive’s Freedom Fighters is a third-person tactical squad shooter – generically, it can be classified alongside Ghost Recon, Rainbow Six, Commandos, SWAT, or other military and police simulators where the player has the power to command a small team of CPU-controlled comrades. Often in these games, players have an extensive range of mechanical and control-functional tools that they can use to direct their squadmates and organize combat strategies. I would argue that one of the fundamental design principles within these games is “exactness,” whereby the player can order their team to perform intricate and context-specific actions that reflect or serve as metaphor for the skills and operating procedures of special forces soldiers.

In Rainbow Six, for example, when the player encounters a closed door it presents a number of mechanical options. They can open it themselves, they can order a teammate to open it while they cover them, they can order their teammate to blow the door open using an explosive charge, they can order their teammates to open the door and throw in a flashbang, they can order their teammates to open the door and throw in a grenade, or they can order their team to open the door, enter the room and clear it using their firearms. This range of tactical expressions is typical of squad shooters. It is characteristic of their generic language.

In Freedom Fighters, players can issue three commands: attack, defend and follow. You can use the aiming reticule to specify an area where your soldiers should defend. You can use the same reticule to send them to attack individual enemies. If you tap an order button, it will issue the order to one soldier. If you hold it down, you give the order to your entire team. There are no other orders that you can give. There are no context specific commands. You can’t choose your soldiers’ equipment. You can’t order them to use explosives, or any weapons specifically. If you reach a doorway, the only “tactical” option is to send your entire squad into the room and bullrush the enemies inside.

Superficially, compared to the genre-bound Esperanto of squad shooters, Freedom Fighters’ mechanical language seems limited and basic. It seems like there are fewer ways for players to express themselves – like they cannot “strategize” and execute their own esoteric plans as might be expected in the ur-tactical shooter. On the contrary, at no point in Freedom Fighters does the “limited” command menu feel like an actual limit, like the player’s control and mechanical influence is deliberately curtailed. The game is intuitive. It’s responsive. It’s fast. You may complete a level using one method, and then replay and use tactics that are entirely different. Compared to its genre peers, the literal mechanics and controls are minimalistic, but the range of possible expressions is equally large.

Via these mechanics and their attendant expressions, Freedom Fighters is able to instantiate and protect its subjective assertions. Allowing the player a high degree of control, and permitting them a large amount of interactive exploration, also, in the case of Freedom Fighters, helps to effect, bind, and calcify the game’s auteured thematic identity. You play as the eponymous freedom fighters. The premise of the game is that you are waging a guerilla war. Your character is a former plumber with no military experience. Your compadres are also ex-civilians. The primitiveness of your available commands is a mechanical analogy of your character and his world. He is fighting a roughshod, ad-hoc campaign using improvised tactics. How you order your squad feels appropriately “rough”, amateur, imprecise.

You might interpret or extrapolate this mechanic further; it can become a metaphor also for the characters’ political, philosophical persuasions. In the fictional world of Freedom Fighters, the Soviet Union beats the United States to developing the first atomic bomb, and ends the Second World War by dropping it on Berlin. The Soviet Union thus becomes the world’s dominant superpower, not America – the game begins when the Russian military invades New York City. The titular freedom fighters are uniformly on the side of American liberty and modern democracy. The USSR in this game is a pastiche of ultra authoritarian, Stalinistic communism. When you give your squadmates orders in Freedom Fighters, those orders are inexact and the squadmates respond to them in equally inexact ways. Using the “defend” command may prompt your soldiers to fan out and take cover. On other occasions, they may all stop still, form a line, and point their guns down the street, becoming a defensive barrier in and of themselves. If you tell them to attack a specific enemy, again, they may interpret your command differently. Sometimes, they will attack that enemy exclusively, from range. Other times, they will charge towards the enemy, firing at any other Soviet soldiers they encounter on the way.

As such, your comrades have their own agency. Within the parameters of the ordering system and the context of a war, they have freedom, liberty – they are not automata whose behaviors are entirely dependent on, and respondent to, the player, but are instead “thinking” individuals. Compared to a squad shooter where the ordering system is more involved and allows for more specific expressions, and a greater range of them, the system in Freedom Fighters reflects a certain “democracy,” whereby you, the player, issue a command, but your fellow guerilla fighters react to it within a degree of variance.

That “democracy” is reflected in another of Freedom Fighters’ mechanics, whereby you can only recruit squadmates after you have accumulated a certain quantity of “Charisma.” By completing objectives such as demolishing objects of Soviet military infrastructure, capturing territory and freeing prisoners of war, you earn Charisma, and the more you have, the more fighters you can recruit, up to a maximum of twelve. Approach a waiting resistance member and attempt to recruit them to your squad without the requisite Charisma and they will refuse.

The game’s retelling of American democracy is simplistic and couched in the country’s national legend, which says that America’s defining characteristic is the primacy it gives to the importance of personal liberty. Nevertheless, Freedom Fighters is satirical. In the same way that the Soviet leader, General Tatarin, resembles physically a Russian bear, Christopher Stone, the player character, wraps his wounds in scraps of the United States flag, and in one scene borrows from the great American parable, Mel Gibson’s Braveheart, by exclaiming at the end of a speech to the gathered revolutionary masses that the Soviets “will never take our freedom.”

What I see in Freedom Fighters is a game that encourages and allows for enormous player agency. But that sense of agency is enabled by a streamlining of mechanics and features rather than allowing the player to operate and participate in a successively large number of mechanics and features. The game is not ludically obtrusive, or even especially esoteric, at least not so that you would notice its esotericism above its other mannerisms. And it allows for, and almost insists upon, a subjective reading – Freedom Fighters has something to say about something, and does not allow for the potency or coherence of that something to be compromised by players’ interactions. It is in fact able to say something with greater volume and clarity owing to the player and how the game permits the player an active role.

Another, cruder way of explaining this kind of game: you wouldn’t know, as a player, that the game is trying to impress something thematically subjective upon you. You wouldn’t feel hamstrung or “shortchanged” in terms of gameplay, or otherwise alerted to its thematic impressions in a way that would make you conscious of them, and therefore unable to process them emotively rather than purely intellectually. And at the same time, the game’s subjectivity is intact. Player plays. Developer and game say something. Neither has to give up any ground.

———

Edward Smith is a writer from the UK who co-edits Bullet Points Monthly.