2024

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #183. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Kcab ti nur.

———

I wonder if the first poet (it’s always a poet) to say the pen is mightier than the sword ever had to face the bullet or the bomb. While I have fairly consistently been of the opinion that words/art alone cannot free us, this has been the year which has made me question whether art is worth anything at all. So much feels empty and trite as the world’s cruelties accelerate and magnify and the system strains but refuses to break – at least not in the ways that will make things better for people.

Luckily for me and this column, there has been a wealth of work engaging with this question that’s come in 2024. One of the most powerful of these is Danez Smith’s Bluff, which opens with the poem “anti-poetica” which begins with the following line:

There is no poem greater than feeding someone

There’s certainly an irony to opening a fairly hefty poetry book with that statement – but it opens the door to actual critical engagement. It’s a challenge, an invitation to put the book back on the shelf if you could be doing something more useful, instead of letting the art about an issue superimpose dealing with the issue.

The question of art’s utility becomes especially mired in complexity when we think about how much of Black/Queer art is eulogy. This is a core question of the more interesting poems of Bluff, Smith contends with the reality that the poems which propelled them in their career are the ones that mourned the dead, whether specific or abstractly. It is rare that the people killed by the state have asked to be in poems, to be on the lips of performers as they receive solemn nods and pronounced clicks in return. The conflicted feelings on this make the book’s inevitable eulogies feel sharper as well. There’s an awareness that we have done this dance before and the junctures where it feels like everything could change are moving closer and closer in time. That we have to find something sharper to meet the moment, instead of repeating the songs from the same hymnbook. In the words of Smith:

If the cops kill me

Don’t grab your pen

Before you find

Your matches.

On the other hand, almost every show this year I’ve been to (or helped organize) has been some kind of fundraiser. For Palestinians facing genocide, for legal defense funds, for gender-affirming surgeries. So, the question of art as usefulness takes another turn, but it does leave us in a chicken/egg situation. Does the art come first or the music? Does political awareness come first or the theatre? Perhaps most importantly, why does it take dancing, shouting and drag for people to take their hands out of their pockets?

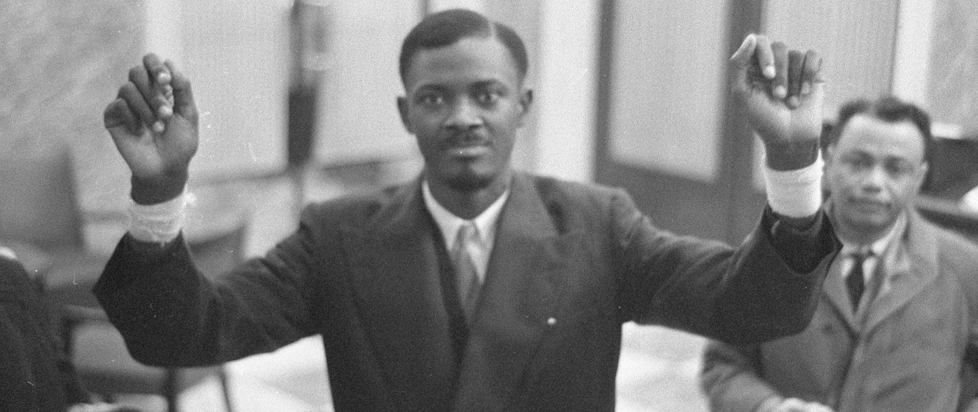

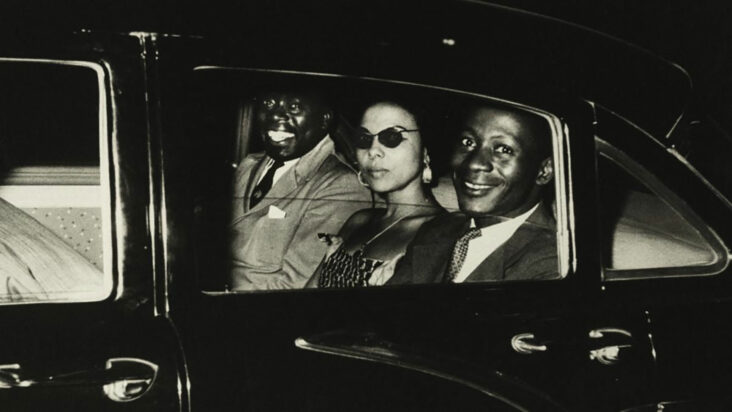

Soundtrack to a Coup D’Etat pushes these questions to a bigger scale. The film is about the assassination of Patrice Lulumba, told through interviews, archival images/footage and the music contemporary to its events. One of the specific focus points is Louis Armstrong, who is on more than one occasion sent to Congo as the “ambassador of jazz,” a fairly transparent attempt by the US government to distract newly-independent Black people from the racism within its borders, and its (neo-)colonial influence abroad. While the film is a really thorough dissection of one aspect of the CIA’s machinations and the active colonial role of corporations, the element I am most interested in for the purpose of this piece is how marginalized people with imperial passports can become the useful idiots of imperialism.

As Johan Grimonprez’s film points out with the example of Nina Simone and the American Society of African Culture, there are many times where Black artists have been tricked into doing the work of the CIA. There are also some artists who have been very happy to align with the work of empire either for money or ideological considerations. However, there are those like Louis Armstrong or Dizzy Gillespie who weren’t exactly being tricked, but still believed that they could do some good and were simply used instead.

Malcolm X acknowledges in the documentary that with intention art can be an effective starting point – something to stir the spirits of the people into action. However, I think it is very tempting to believe that just by being a presence, artists can do good, and that marginalized art existing for its own sake can be the salve that heals the world. It’s even easier to believe in the inherent good of art when the less morally dubious opportunities pay so well.

However, there is a responsibility to the people of the imperial periphery to not be complicit in the violence done against colonized peoples, regardless of our own positionality within the imperial state’s borders. We should not trick ourselves into thinking we are doing something we’re not. In this, we can look at work like Hamilton, how its widespread success served to sanitize the American national project, made most apparent when his taking of the show to Puerto Rico was critiqued and protested by the students of the university he intended to stage it at.

Mati Diop’s Dahomey is another film interested in whether anti-colonial cultural gestures mean something in the face of everything we are facing. The front half of the film narrativizes the journey of 26 statues from a museum in France back to Benin – with a particular focus on the one representing King Ghézo. The statue is given voice and that voice is full of fear and doubt, a gladness to be going home but an apprehension at what will be found on the return. After all, the statue is not being returned to be a living part of the community, it is instead entering a different glass box, albeit one owned by the descendants of those who initially revered it. One of the central questions of the film is whether the museum in all its sterile taxonomy can really be a point of power for communities.

The back half of the film is an edited down recording of a debate being had between students at the University of Abomey-Calavi on the return of statues by France. Some find the gesture a useful starting point, others find the small scale of the returns to be insulting. Some find the gesture genuine and others think it is a cover for the continuing exploitations and the refusal to make material reparations. Diop is very deft in how she quietly shifts attention between different parts of the discussion, creating a compelling summary of a much longer occasion without butchering the debate. She also surrounds the discussion with shots of the everyday lives of the Senegalese people, as if to dare you to ask whether this matters at all.

In many ways this is a column and a year of questions. There are no simple solutions and there is always work to be done. But it must be done with genuine self-reflection and a refusal to take easy answers, or easy money either. With this in mind it is again worth returning to the words of Smith:

let us not be scared of the work

because it is hard

let us move the mountain

because the mountain must move.

———

Oluwatayo Adewole is a writer, critic and performer coming to you live from the British and Irish Isles. You can find her roaming the streets on his bike or at https://tayowrites.persona.co/ if you’re at a more pedestrian pace.