Zoning Out

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #180. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Analyzing the digital and analog feedback loop.

———

There are two pieces of dialogue that I believe were the most significant to my first watch of It Follows, which features a fatal curse that is transmitted seemingly through sex. Neither quote has to do explicitly with sex or death, despite the fact that one occurs shortly after a sex scene and another shortly before a confrontation with a near-death experience. The first is Jay’s as she idly reminisces after sleeping with her so-called boyfriend Hugh in the back of his car. She relates how her childhood desires to date and travel with a partner up north out of state weren’t really about those experiences themselves. “It was never about going anywhere . . . just having some kind of freedom, I guess. Now we’re old enough, but where the hell do we go, right?” Her hand trails through some flowering weeds below her just outside the open car door. Hugh and her are parked in a dirt lot outside of a derelict factory building, a sight straight out of an urban exploration video. Considering that the movie was filmed in Detroit by a writer-director who’s a native of that city, the blurring of opposing affects that a location like this can inspire is very intentional.

David Robert Mitchell has stated previously in an Anthem Magazine interview that it’s an important place for him and that “[It] had to be there . . . Also the very tragic separation between the city and the suburbs was another aspect or theme of the story. It’s there in the foreground in a few places, but that’s also part of the subtext of the movie.” The setting of It Follows is also deliberately anachronistic, referencing both how there’s always a slippage of culture between generations and how nightmarish experiences are difficult to rationalize. Detroit’s suburbs being treated in this manner also speaks to how dereliction isn’t a direct signifier for danger. If anything, there can be markers of historical heritage in abandoned ruins or proof of mistreatment due to class stratification.

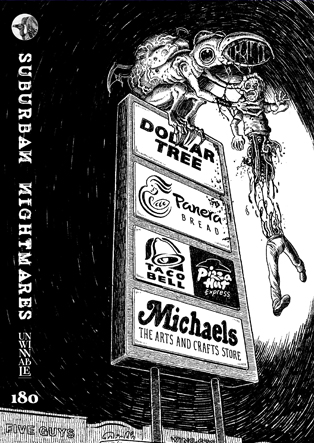

Several scenes of this movie feature such desolate settings and all of them portray the parts of suburban life that the more privileged set don’t want to perceive. The poor parts, the drug-ridden parts, the sordid and physically unkempt parts. The boundaries of suburbs are explicit, as is its stratification of both individuals and families. The beginning of suburbs in America was a mixture of redlining practices to keep out non-white homeowners and a yearning for separation from an increasingly industrialized and chaotic working life in cities. We also know from works like Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law that redlining wasn’t the only practice that drew the borders between suburbs and ghettos, as well.

There were crooked federal practices as well as real estate and bank practices that encouraged white flight and housing discrimination that is, as Rothstein aptly states it, akin to second class treatment that’s a relic of slavery. In Canada, suburbs arose as a rejuvenation effort after the second world war and the Great Depression. In both instances, suburbs were created to sate predominantly white middle- and upper-class desires for comfort, convenience and a return to familiar (often prejudicial) conventions. A precursor of the MAGA or one could even say the MNAGA or “Make North America Great Again” alt-right movement.

The unspoken fears of losing these things to change and outside influences also birthed prejudiced surveillance. Think of the concept of the neighborhood watch and homeowners associations, double-edged entities that unite the community by surveillance and the internal policing of each other. Like the fellowship that forms out of witnessing Jay’s abuse and subsequent distress by Hugh and the supernatural presence that stalks her, suburban communities espouse kinship and a sense of responsibility.

But these communities can also be suffocating and suspicious of each other and their values as well. Near the start of the troubles in It Follows someone comments on seeing the police checking on Jay’s house after a break-in from the monster that her family is problematic. The neighborhood watch is always active or at least perceived in horror movies as well as dark faerie tales like Edward Scissorhands. Even if the neighborhood watch is not explicitly acknowledged, as in my favorite segment of the anthology XX, “The Birthday Party,” its force is perceived in the desperation of a housewife attempting to hide her husband’s dead body because she’s constricted by previous plans for a lavish party for her daughter. She’s also struggling with the discovery that her husband has committed suicide and doesn’t want her family’s image to be judged by the toxic gossip of the suburbs. Suburban fears are often entrenched in artificial constructs or the illusion of greater control over one’s own life and its perception.

This brings me to the second dialogue quote that resonated with me from It Follows. Yara, part of Jay’s inner circle and the bookish misfit archetype of the group, explains as they travel to the pool on the outskirts of town to confront the wraith:

“When I was a little girl my parents told me I wasn’t allowed to go south of 8 Mile. I didn’t even understand what that meant. It wasn’t until I got a little older that I realized that was where the city started and the suburbs ended. I started thinking how weird and shitty that was. I had to ask permission to go to the state fair with my best friend and her parents just because it was a few blocks past the border.”

Jay replies in a solemn tone that her parents told her the same thing about approaching what they considered the outer bounds. As someone who lives in a pandemic society and has lived in both the city and a rural neighborhood on an island, I read this exchange as a cautionary double-take. On the one hand, the girls’ parents aren’t exactly in the wrong for wanting them to be careful of straying too far into territory that could be dangerous for them. But on the other hand, there’s also an assumption that danger doesn’t occur within the strict physical and social boundaries of the suburbs. These boundaries can feel arbitrary and suffocating to teens. Especially teens who are assigned female at birth and already dealing with the boundaries of their bodies in space and how they perform within both. You notice that in both instances that Jay and Yara comment on traveling and being in locations that are new to them, they emphasize that it’s less about reaching a specific destination than it is about the experience of being free to do whatever they wish in these other places.

For Jay, it was about having a romantic connection with a partner who wants to go on a road trip. For Yara, it was about spending quality time with her best friend. Being anywhere is better than trapped in the suburbs. Except, as is discussed by Joni Hayward in their Frames Cinema Journal article on the economic subtexts of It Follows, once Jay and by extension her inner circle is affected by the curse they are forced to be in constant movement. Suddenly being mobile and having a change in scenery are markers of struggle. As well, Jay mentions that she didn’t know where Hugh lived because he felt ashamed of his home. It’s noteworthy that both of Hugh’s abodes, the rundown squatters’ house he was absent from and his family home where he’s actually located, suggest that his shame could stem from living in either situation. Both homes are often made part of a conservative narrative of young generations failing in neoliberal America.

Hayward sees this dynamic as being a way to comment on post-2008 recession America and how uncertainty and lack of choice are common for millennials. As one of the generations most affected by these illusory neoliberal ideals of choice and upward mobility, you could say the curse is more akin to economic horror than pandemic horror, though there’s a convincing case to be made about how touch and disease are central to how the curse is carried out as well. Not to mention the invisibility of the monster and how that creates a narrative of how mental health has been impacted by either aforementioned force.

In fact, I’d like to end on the topic of the invisibility of these boundaries of the suburbs, existing and enduring within said boundaries and the intersectionality of the curse’s manifestation which possibly transcends these boundaries. Or at least chafes against them. One could say that the suburban nightmare of It Follows is trauma and how it’s pervasive in spite of the artificial and performative boundaries of the suburb.

The curse hobbles Jay’s near-perfect social record as a beautiful, middle-class and white cisgendered girl who’s doing well in school. She gains the curse in a way that is perceived, initially at least by others, to be a consequence of her being a girl going out with the wrong person to a questionable area of the suburbs. Her distress is read by her friends as PTSD from sexual abuse for most of the film, until there’s undeniable proof of Jay’s haunting at the beach during a retreat. The curse often takes the form of naked or near naked disheveled women for Jay, when it’s not taking the form of vulnerable individuals like the elderly or children or appearing as those from Jay’s inner circle. This suggests that the curse, especially considering how it gets transmitted to others, often afflicts the most vulnerable of society. The poor, children, the elderly, women . . . yet this curse is one that doesn’t remain isolated to the afflicted. This is most likely why It Follows remains relevant years later during a pandemic.

The curse can spread throughout communities without regard for social status or other artificial boundaries a suburb contains. And although the curse afflicts the most vulnerable and marginalized because of the socioeconomic constraints, it isn’t discriminating. Yet as was mentioned in an A.V. Club interview, the curse doesn’t truly map onto a disease narrative, because the afflicted can in some instances completely transfer the threat and its symptoms to someone else. Like the layers of constricting boundaries within the suburbs, the curse is more temporal than anything. A curse that remains invisible yet still inflicts strife and disrupts those who are not directly affected.

Perhaps this curse in It Follows is just a natural legacy of segregation and white flight. I noticed that the only notable non-white character in the film is one of Jay’s teachers. When Jay sees the thing approaching her across the school courtyard from her window, she ignores her Black teacher as she hastily packs up and leaves the class in the middle of a lecture. This teacher is not affected by the curse in any way, a rare instance for a horror film such as this. Jay’s fear makes the teacher invisible to her as she flees. The boundaries of suburbs started as a predatory tactic to supposedly safeguard white American culture and values. Is it any wonder that these arbitrary and suffocating lines between race, class, gender and ability would perhaps result in a menacing force that could disregard these boundaries?

It’s revealed at the end of the film that the last form the curse took as it tried to kill Jay at the municipal pool was of her father. As Leslye Finn noted in her Longreads article, brilliantly quoting and analyzing Carol J. Clover’s concept of the Terrible Place, such places are both nostalgic and protean. The whole of the suburbs can be a Terrible Place.

———

Phoenix Simms is a writer and indie narrative designer from Atlantic Canada. You can lure her out of hibernation during the winter with rare McKillip novels, Japanese stationery goods, and ornate cupcakes.