Glimpsing the World’s True Scale

This is a reprint of the feature essay from Issue #80 of Exploits, our collaborative cultural diary in magazine form. If you like what you see, buy it now for $2, or subscribe to never miss an issue (note: Exploits is always free for subscribers of Unwinnable Monthly).

This is a reprint of the feature essay from Issue #80 of Exploits, our collaborative cultural diary in magazine form. If you like what you see, buy it now for $2, or subscribe to never miss an issue (note: Exploits is always free for subscribers of Unwinnable Monthly).

———

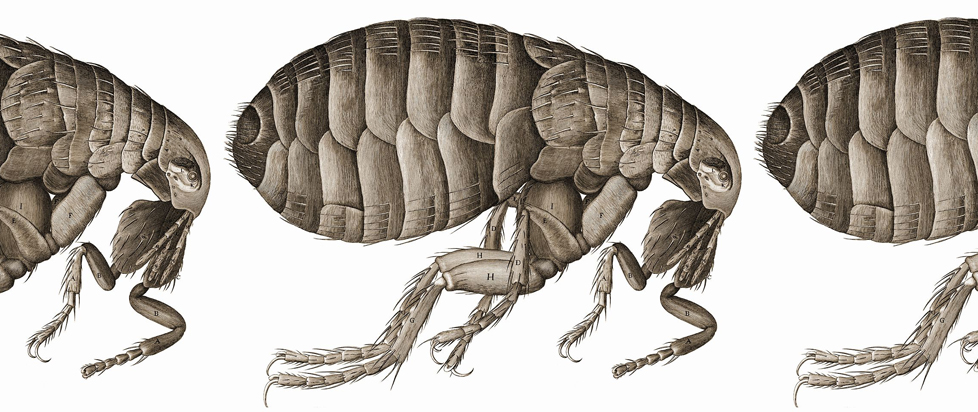

When I picked up the book Micrographia, it fell open to the foldouts, spine creased and pages yellowing as if a thousand people before me had flipped to this exact spot. The delicate paper unfurled to reveal what a contemporary called “a flea the size of a cat.” Endlessly jointed legs, plates of chitinous armor, hairs that look like spikes – it’s hard to believe this is the same creature that appears as a minuscule brown dot to the naked eye. It is frightening and strange, something mundane revealed to be horrifying in its detail. To the people reading this book in 1665, when this was the first drawing of a flea under a microscope ever published, it must have been breathtaking.

Cocoon is a game obsessed with scale. The orbs you use to solve puzzles are each their own world, which you can shrink down to enter before jumping back out into whatever world they are nested in. Throughout the game, I thought I understood the scale of this universe: the orange and green and purple worlds all fit into the gray one, which was clearly the real world, the final one. Until hours into the game, you reach a portal in the gray world and jump up and out, watching as everything you’ve known shrinks into a space no wider than your arms.

There is a sudden realization that comes with these moments. The tiny brown speck of the flea suddenly has minuscule eyes and clashing mandibles, an alien living on the tip of your finger. The world you thought contained everything is now dwarfed by its surroundings, the vastness of the universe wider than you thought possible. You become insignificant, an awkward middle size between the delicate creatures surrounding you and the infinite space between the stars.

The world is the same as it’s always been, but you have glimpsed its scale for the first time.

Robert Hooke, the author of Micrographia, said of his discoveries that “in every little particle of [the Earth’s] matter, we now behold almost as great a variety of creatures as we were able before to reckon up in the whole Universe itself.” These drawings went beyond simple scientific illustrations – they changed how people fundamentally saw the world. Through the microscope everything became infinitely more detailed, each tiny bug and plant containing multitudes never thought possible. It was terrifying and beautiful in equal parts.

Can you imagine seeing the crystals of a snowflake for the first time?

Cocoon continues to warp your sense of scale throughout the game, sending you deeper and deeper into nested worlds only to have you zoom out further than ever before. The end of the game is one continuous shot outward, the worlds nested within worlds nested within worlds shrinking to nothing in the face of planets, those tiny next to stars, those dwarfed by the size of the solar system. In its own way, Cocoon is recreating the feeling Micrographia must have elicited nearly 400 years ago, the feeling of suddenly understanding that there is more within the universe than you will ever know, that your existence is nothing in the face of its infinite detail, that “some parts of it are too large to be comprehended, and some too little to be perceived.”

You are tiny. You are enormous. You will never know your true scale.