Killing the Dragon

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #176. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

What’s left when we’ve moved on.

———

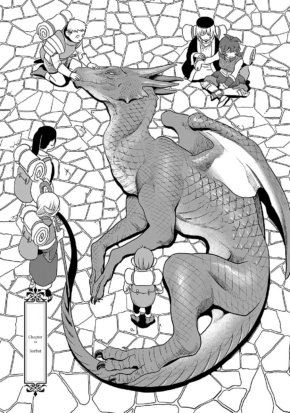

The climax of the first coeur of Delicious in Dungeon earlier this year was actually a rematch. The anime, which is based on the manga of the same name that ended last September, is about a group of adventurers who search for the main character’s sister in a dungeon and eat the monsters they find there as sustenance. Dungeon Meshi (the manga’s name in Japan) is concerned with how ecosystems are built and maintained. Some of the most beautiful panels are floor to ceiling shots of the dungeon showing how a small organism – a worm, or a tuft of grass in a sunbeam – feeds a bird, which feeds a fox, which feeds a wolf monster, which feeds a person. The logic of ecosystems runs under every page, drilling into the reader two essential facts: every living being is always searching for food, and eating means preying on something else in the ecosystem with you. As soon as that ecosystem is disturbed, chaos.

Around the time I finished reading Dungeon Meshi I also played Katamari Damacy, a game about rolling up the world.

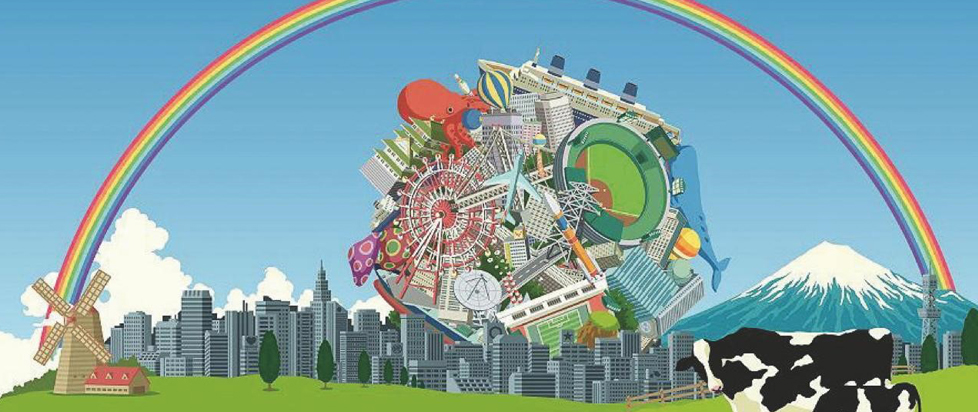

Katamari Damacy is a high-score game where your job is to roll up everything – literally everything, from furniture to animals and books, candy and buildings. As your katamari (the orb of stuff you’re rolling up) gets bigger, you can roll up bigger stuff. It could go on forever, except that eventually you run out of stuff to roll up, except then you can redo the levels to get higher scores.

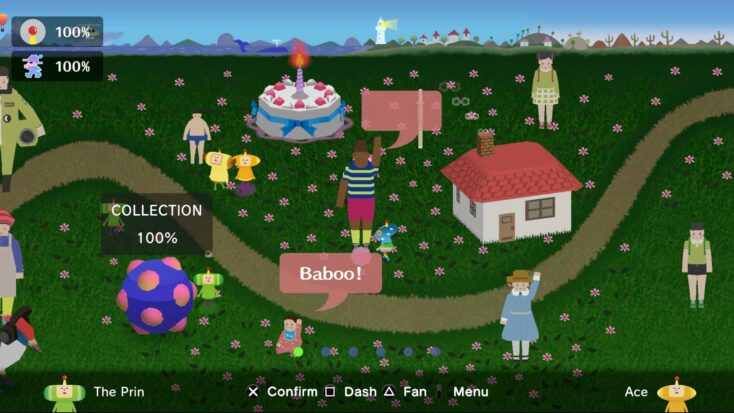

Nothing in Katamari Damacy is ever scary. Yet individual pieces sometimes become horrific. The ghost level where you have to collect instruments, for example, while hounded by the voice of your disapproving dad. Or the noises people make when you roll them up, the sound you might make while being dissolved in a vat of acid. Not only can it be unnerving, it’s also hard. The hardest level is where you have to light a campfire with your katamari and roll up enough kindling to keep it going. Finishing this level was hell. I had to get my boyfriend involved, who was more goal oriented and less distracted by katamari parts placed to lure you away from the main path. The other thing about the entry I played, the second game in the series called We Love Katamari, is that even if you finish a level in time, there’s a high chance you’ll be shouted at by the King, the game’s narrative voice, because you didn’t do it perfectly. This happened in the campfire level, where the katamari-requester (the game calls them fans) described ours as “just a lit match”.

Everything is all about scale in Katamari Damacy. The King is huge, blotting out the sun when he appears. You’re tiny even in comparison to your katamari. The goal is always to get bigger, or to get bigger faster, except for the handful of times when you need to hit a certain size. The narrative of the game is also built on growth. We Love Katamari was only made because of the first game’s success, and the fans’ reactions are a response to the pressure Keita Takahashi felt to create a sequel. In Takahashi’s narrative the people asking for more are shrill, rude; in the King’s case, they are responding to what looks a lot like childhood abuse. Lest you get too serious about this dark sub-story, the gameplay is light and fun; it’s only the scoring that reminds you growth is the only thing that matters.

Is there a katamari ecosystem? If so, you’re right at the top. You might even be above the king, since you’re the one in charge of the orb. The end goal of We Love Katamari is to roll up the sun, a task that’s existentially paralyzing. Every cat, hairclip and deck of playing cards, all the signs of life in the world, against the heat and light that make that life possible? I couldn’t really believe it when I made it to the credits; I was sure the game would stop me before I got outer space involved. But no; you can roll up all the katamari planets you made and launch them like a bowling ball. Life against life, and the bigger life wins.

Watching the supernova explode onto itself, I thought back on Dungeon Meshi, which also ends with a big blob of people. The ultimate villain, a desire demon, absorbs everyone on the island except the main characters into an alternate dimension where there are no energy limitations and consequently there’s no ecosystem. Readers of the comic, having learned about ecological organization for ninety chapters, can see this is a tragedy. The demon’s promise of something for nothing is empty, because even in a world with magic something has to be given up for the transaction to be made. Main character Laios banishes the demon to the realm of feeling nothing, and the other world spits out everyone who was taken. Their ending victory is remaining differentiated.

Even earlier in the comic, at that climax I mentioned at the beginning, we’re taught the danger of combining oneself with another. Marcille uses black magic to extract Falin, the sister they’ve searched for, from the dragon’s belly, but something goes wrong and Falin turns into a horrible monster. It turns out the dragon’s essence stayed with Falin when she was resurrected. The soul is like an egg, we’re told; you can’t put the yolk back in a broken shell once it’s mixed with another.

Where Dungeon Meshi’s thesis about nature rings loudly, Katamari Damacy never bothers to assert one at all. And why would it? It’s a game about rolling up every day Japanese objects. Yet, its conclusion – life against life – is the first time the actions we’ve taken seem like they might need some justification. Is the world OK? We’re told that it is. But the king is troubled over whether or not we did the right thing. Is rolling everything together – for what, pleasure? – worth the pain we might be causing, even temporarily? You can go back to the katamari neighborhood to get your high scores, and everything seems as it should be, sunlight included. But there’s still the sense of wrongness that you can’t put the egg back in the shell, or pull the katamari back out of the sun.

Dungeon Meshi and Katamari’s restorative endings feel good because the worlds they create are so vivid. Both the game and the comic have beautiful environments, lovingly drawn details, and artifacts of Japanese culture from candy to national dishes. Why would you pass by such things without appreciating them? The ecosystem of the world, when viewed from a distance, is random and cruel; viewed from up close it becomes understandable, if still unfair. Both Dungeon Meshi and, in its unique way, the Katamari franchise ask you to zoom in and look closely, keep your eyes peeled for small details, and never forget them even when they’re a speck on the surface of a massive star. A huge, unstoppable force – nature, or capitalism, or a really big monster – isn’t one thing, but is made of a million component parts, and knowing about those parts is how you can accomplish understanding and survival. Paying close attention to tiny things, in other words, is the only way to live.

———

Emily Price is a freelance writer and PhD candidate in literature based in Brooklyn, NY.