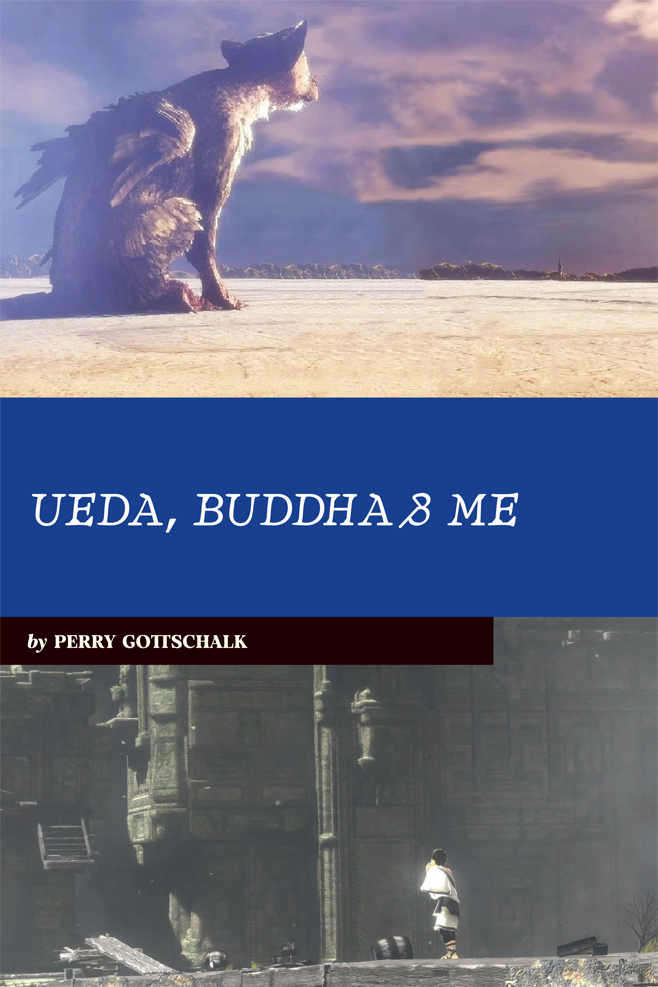

Ueda, Buddha & Me

This is a feature excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly #173. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

The whole of human history stands to tell us one thing: we suck at letting things go. Though extremely reductive, it isn’t a stretch to say that at the heart of everything ranging from war to art, there is someone who could not bear to let go of something. Perhaps attachment, the antithesis of letting go, is a universal truth of humanity that we cannot separate ourselves from.

I’ve always had a complicated relationship with 2016’s The Last Guardian – and in this way I too find myself attached. I championed Fumito Ueda’s games as the most essential entries to the videogame canon. “These are works of art!” I would cry. “It’s one of the most incredible experiences you can have,” My tone shifts: “It’s also one of the most frustrating games you will ever play.” Truthfully, many shouldn’t play this game. You spend a dozen hours issuing commands to a giant bird-dog-cat thing who won’t listen to you. Even if it’s the point of the game to be frustrating, it’s still just plain frustrating.

You can see the conflict I feel. It’s akin to telling someone “This TV show is absolutely amazing. Once you get to the third season.” That’s a huge time investment for someone to make for anything. My friend swears that Dota 2 is incredible once you really understand the game – once you’ve got anywhere from 100 to 500 hours under your belt. Time is a precious commodity that most don’t want to spend unengaged or frustrated. No matter how high quality The Last Guardian is, any recommendation I make to another person will always have this underlying recognition that it may not be worth the initial investment to them.

Ueda’s prior title, Shadow of the Colossus, requires no such conflict in recommending. It’s what initially informed me that videogames could be something more than entertainment; they could speak to the soul and offer insight into the human condition as works of art. Ueda’s approach to game design, what he calls “design by subtraction,” reveals the beauty of his games. Ueda carefully reviews each detail of the game – mechanics, narrative, assets, everything – and pares them down until only the base essence of those details remains. Does the player having access to an item inventory improve their experience? If not, do away with it. Damien Mecheri, in The Works of Fumito Ueda: A Different Perspective on Video Games, notes: “Ueda soon realized that to create the best experience possible, he had to be sure not to make it more complex, but actually to simplify it, and make it as short and dense as possible.” Ueda has likened this process to sculpting from a block of marble: through the act of removal, of letting go, you uncover the work within.

This process differs from a more traditional design approach, where mechanics are added and iterated upon to flesh out a game. Ueda has always strived to make games that stand out from the other popular games, but his subtractive approach in an additive world doesn’t point towards rebellious impulse for the sake of agitating the player. Ueda simply asks that the player allow themselves to be humbled. Forget what you know about other games. Let go of that knowledge. There are no character stat screens or inventories here. Don’t come to these games as experts of others, come to these games as someone who has never played one.

Unsurprisingly, this humbling of the player opens them up to sincere emotional beats. The defining moment of The Last Guardian comes near the end of the game. You, an unnamed boy, and your companion Trico, the giant bird-dog-cat thing, have returned to your home village. By now, the game has revealed that Trico tore you from this community in order to feed you to an unknown para-cosmic entity, though through the events of the game, the two of you have formed a bond that overrides Trico’s instinctual programming. You and Trico would go to the ends of the earth for one another, despite the rocky beginning you had.

The villagers don’t understand this. They see a monster that threatens their families. They gather with pitchforks and torches to drive Trico away. Your family carries you to safety, away from Trico. Never mind that Trico has been your sole protector throughout the game: he is a beast. The people lunge at Trico, stabbing him with spears and burning him. You, carried over the shoulder of a villager, see him cry as he is harmed. He can fly away at any time – he does not have to subject himself to this physical pain. You realize he is actively choosing not to leave. He will not forsake you, his partner. All you can do now is command Trico to save himself, to flee to safety. He does not listen. The bond the two of you have formed prevents him from doing so.

I witnessed this scene unfold through water logged eyes, mashing buttons on my controller between sobs to urge him to preserve his own well-being. The big, dumb animal I’d grown to love would not – Trico keeps looking for any way he can reach me, to remain together. It isn’t until he is one more pitchfork away from death that he leaves, his sense of self-preservation finally outweighing his heart’s desire. He lets go.

Trico is gone now. I need to pause the game and collect myself.

The game doesn’t pause. No buttons respond. My controller died.

I missed that notification somewhere along the way, gripped by the emotional climax. Maybe the battery ran out while urging Trico to flee, or maybe before the scene prior, there’s no way of knowing. I realized I didn’t want to know. Witnessing this creature who loved me enough to put himself in harm’s way, near death, to avoid being separated was volumes more powerful than whatever player input I could have had in that moment. If my controller had been responsive, would Trico have listened to me and flown away earlier? Who knows. I didn’t wish to find out. I was okay with letting go of this “what if?” in favor of the experience I had. This is the space that Fumito Ueda puts us in through design by subtraction. To let go and experience.

Perhaps then, my conflict in recommending this game partially comes from knowing that this moment is unreplicable. The odds of someone’s controller dying at that exact moment is unlikely – they will never be able to feel the same thing I felt while playing. Hell, I can never play this game again myself. I would shatter this precious moment by knowing how this sequence could actually play out.

Design by subtraction isn’t an idea original to Fumito Ueda. As mentioned, it’s reminiscent of marble sculpting; one strips away all unnecessary elements until the work underneath is excavated. However, this process has little to do with the act of emotionally letting go. Ueda’s works bear more in common with the concept of Shoshin, found in Zen Buddhism. Dōgen Zenji introduced the concept in the thirteenth century, teaching that one should approach even familiar experiences with a sense of curiosity. When one holds expectations of a specific circumstance, they can often fall victim to those expectations and alter their experience. Instead of this, one should utilize Shoshin, or directly translated, the Beginner’s Mind, to open themselves up to a truer interpretation of the world.

A counselor once described it to me by describing a trip to the grocery store. It’s my least favorite activity: I can only handle navigating a labyrinth of spatially unaware shoppers putting their carts in the middle of the aisle for so long. “If you go into the store expecting to be enraged at others – guess what?” she says. “You’ll be enraged.” I consider the obvious truth of her statement before she continues, “If you go into the store only curious about what will happen, sure! You still might walk away mad. But maybe something else could happen that has you leaving the store feeling something else.”

———

Perry Gottschalk is a Colorado-based writer, thinking about games and the way they make us feel. For more feelings, follow @gottsdamn on Twitter.

You’ve been reading an excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly Issue 173.

To read the article in its entirety, please purchase the issue from the shop or sign up for a subscription to Unwinnable Monthly!