Sam Porter Bridges Redefines the Anti-Hero

Anti-heroes are almost inescapable within the gaming landscape, and I’ve grown a distaste for them. It’s not that I have an inherent aversion to the archetype, but rather, I detest the overabundance. All things become tiresome with excess, and anti-heroes are no exception. Although, no matter how much its overuse tires me, I can’t claim befuddlement. It’s evident how well the archetype accommodates the medium’s wishes and requirements.

It is undeniable that most games center around violence in some shape, and due to the hours the average game takes to complete being well into the double-digits, the protagonist will have racked up quite a monstrous body count before the credits roll. A level of bloodshed befitting very few. Leaving two options: ignore the ramifications or cast a protagonist who would present no qualms with such carnage.

Anti-heroes, without a doubt, are the best-suited solution to such an issue. It treads the thin line between the villain and the hero, fitting the bill without dipping too far into the depraved, allowing us to relish in the violence and chaos we inflict while still feeling like a hero in some regard.

It doesn’t seem like this should matter in the slightest. It’s fictional, after all, but it seems this violence is still a bit more difficult to stomach if the ends are equal in rottenness to the means, even within a fictional context.

Of course, it’s not as if all violent games choose the anti-hero, and some games will cast them without a gameplay-driven need. It’s hard to know what the best option is, but more than not, turning to the odd and the indie has the most promising chance at delivering me a transient escape. One such bizarre game seized me with the criticisms lobbed at it. Panned as a monotonous walking simulator, Death Stranding mesmerized me. Criticism to some can be an endorsement to others, and all the criticism levied against it worked to elevate my excitement.

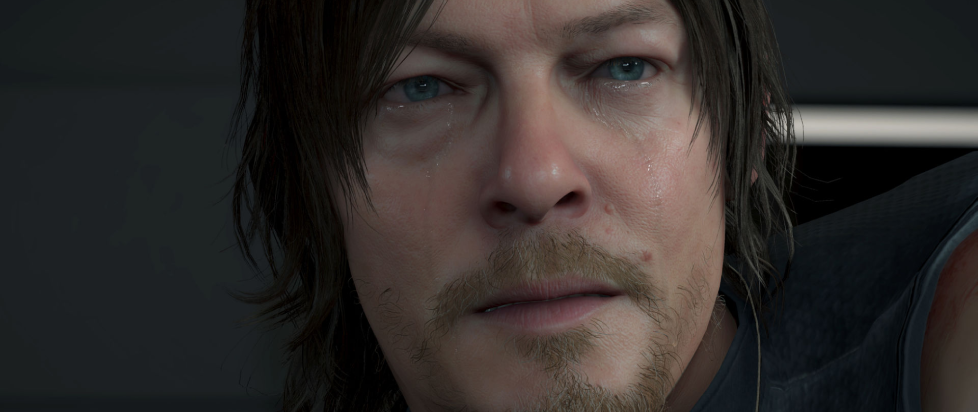

After having just played a plethora of action-orientated games, I had hoped it would be the refreshing experience I needed, and the gameplay it offered was some of the most unique and relaxing I had ever encountered. But despite being an endeavor to escape the anti-hero, I was shocked when I met a protagonist who resonated with me in a manner that didn’t bode well. Sam Porter Bridges was a “Literally Me” protagonist.

Somewhere between a meme and a legitimate label, “Literally Me” is applied to outcast characters who exude loneliness, are plagued with mental illness, and hold pessimistic views. It isn’t an interchangeable term for anti-hero, though nevertheless, these characters often express themselves through violence, making them at least anti-heroes and, at times, villains. I understand that people find this violence a cathartic release, but I take issue with it. When the reasons I have to relate to someone translate into heinous actions, the individual ceases to be as relatable. I was almost certain Sam harbored this label, and I was concerned that his descent was inbound, that this attempted escape was hopeless. Yet, as the narrative unfolded, I discovered something that surpassed the short vacation from the typical that I had envisioned this to be.

Sam did indeed deserve the label. Living in a world where purgatory and the material realm have become intertwined, Sam is among those gifted with a more significant connection to the other side, allowing him to sense the departed that now ramble. It’s a blessing, but not without containing an equal curse. Horrific nightmares plague his sleep. And when he attempted to settle down with his wife, she became infected with these same nightmares after becoming pregnant with his child. Unable to handle them, she committed suicide, sending Sam into a spiral of guilt and anguish and irritating an old wound – aphenphosmphobia, the fear of human touch. Sam had suffered from this condition before meeting his wife, and though he had thought it wouldn’t return, there was still a slim prospect of relapse in the case of a traumatic event.

After this unexpected occurrence, Sam chose to bore the position of a porter in a world whose need for them was desperate. It’s a noble charge, but not one he chose from a sense of altruism, instead the total isolation it entailed. Spending his time delivering packages to those in dire need, Sam represented hope even while hopeless. All the hope he once held had died alongside his wife and unborn child.

When we first meet him, he is a shattered man, alone, disconnected, unable to move forward, cynical, and cold. I kept watching and waiting for the descent I had come to expect, the culmination of his trauma and suffering to be vitriolic violence, a rebellion against the world that caused him this suffering. I waited, but it never arrived. Nothing ever did, not that he didn’t change, but Sam didn’t need redemption. His actions remained consistent. It was the reasons for those actions, however, that changed. As he started to connect to those he delivered to, his toil became more than a means to isolate.

What had started as nothing more than a desire for something different than what I had come to expect from the medium ended with me discovering a protagonist who subverted expectations, whose trauma and troubles weren’t used as an excuse to turn him into an anti-hero, who changed and grew throughout the narrative, and who is one of the most memorable protagonists I’ve ever encountered.

Sam is a welcome surprise, a hopeful alternative to the usual cast that dons the label. He isn’t a cautionary tale. Something these “Literally Me” characters often are and sometimes something that those who idolize them will ignore. Sam is, instead, someone to aspire to, at least in some small measure, even at his lowest point. I understand those who love these characters don’t want to emulate the violent conduct exhibited, but Sam’s actions are worth emulating, as is his change and growth.

———

John Anderson spends far too much time thinking about videogames and not nearly enough time playing them.