Spacemen & Dinosaurs

This the cover story of Unwinnable Monthly #166. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

The recent Adam Driver SF/action vehicle 65 is about a space pilot from a long time ago in a faraway star system, if not galaxy, who crashes on Earth in the hours preceding the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event. (“65 million years ago” as the movie laboriously spells out.)

With this premise, 66 would have been a more accurate title, but that might’ve befuddled Star Wars fans there to see Kylo Ren fight a T. rex, and anyway one look at this film’s prehistoric fauna is enough to know that scientific rigor is the least of its concerns.

Driver’s character, Mills, meets the crash’s only other survivor – a young girl named Koa, played by Ariana Greenblatt – and spends the rest of the runtime protecting her from “dinosaurs” that often look and behave more like hybrid monsters from a rejected Jurassic World spinoff. Despite being arguably better than the latest installment of that franchise, 65 is not a very good movie. It goes down a lot easier, though, if you’re a fan of a particular microgenre: that of spacefaring humans (or, in this case, humanoid aliens) encountering dinosaurs on an unfamiliar world. It’s a small and unglamorous field, but more persistent than one might think.

Interplanetary explorers have been encountering dinosaurs or dinosaur-like creatures in fiction for more than a century, but the originator of this premise in cinema seems to be King Dinosaur. Released in 1955, this directorial debut of the recently late B-movie monarch Bert I. Gordon has all the core elements: four astronauts travel to a rogue planet newly arrived in our solar system (dubbed “Nova”) and discover a variety of Earth-like animals including carrion birds, prehistoric mammals and reptiles, and the titular “king” himself – really a gigantic iguana, depicted as all the big creatures are via enlarged “slurpasaur” effects.

After escaping their immediate peril, the astronauts decide to set off a nuclear device as their parting gift, wiping out an entire island of wildlife in their zeal to “bring civilization to planet Nova.” King Dinosaur was cheaply made with a small cast and liberal use of stock footage, and the result is both sillier and less entertaining than it sounds, especially considering the obvious harm done to some of the animals used.

The cheap trend continued with America’s next film of this type, Curtis Harrington’s Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet (1965), itself the first of two Roger Corman-produced direct-to-TV adaptations of the 1962 Soviet film Planeta Bur (Planet of Storms in English, directed by Pavel Klushantsev). The original depicts a manned expedition to Venus that is crippled by a meteor. The remaining cosmonauts land to find a poison-aired world of misty swamps and rocky volcanoes, populated by sluggish sauropods, floppy pterosaurs and hopping, man-sized predators brought to life by actors in rubber suits.

I assume these last are meant to evoke some kind of large dromaeosaur or small tyrannosaur, though more than either they bear a delightful resemblance to Godzilla – or at least the Big G’s underpaid stunt double. Harrington’s version reused most of the original footage, dubbing over the Soviet actors and editing in new scenes with horror notables Basil Rathbone and Faith Domergue as a pair of scientists monitoring the mission from afar.

The second adaptation, directed (and narrated) by Peter Bogdonavich in 1968, swapped these for even more new footage starring Mamie Van Doren and several other attractive actresses as beach-dwelling Venusians. The resulting Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women, as its title suggests, shifts the focus somewhat from rubbery beasts to seashell-clad babes. Both films are pseudonymous splice-jobs, with the American-filmed scenes diluting more often than adding substance. Each is worth checking out if you’re a Corman completist or just into this sort of thing; if you only have patience for one, I’d skip both in favor of the Russian original.

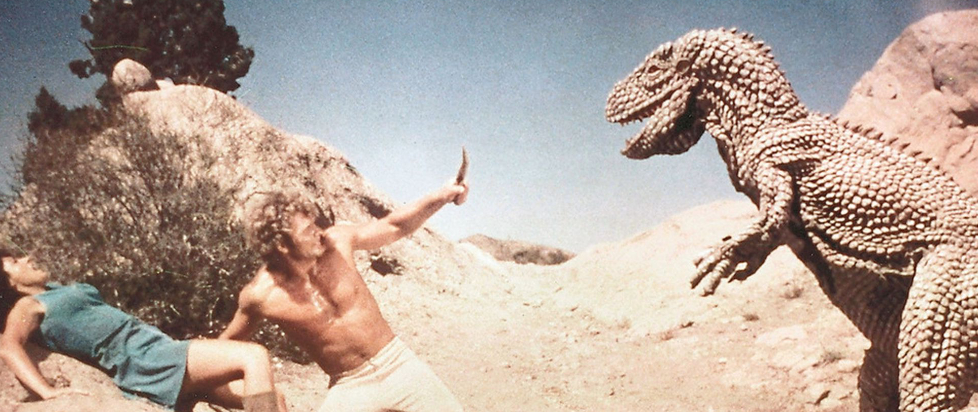

Perhaps the jewel in the Spacemen & Dinosaurs crown came in 1977, with James Shea’s Planet of Dinosaurs. In this take on the formula, a spaceship crashes on an Earthlike planet many lightyears from our solar system. The stranded crew, having lost their only means of interplanetary communication, resolve to survive in their new environment while battling or evading an impressive menagerie of stop-motion dinosaurs featuring stegosaurs and ceratopsians, sauropods and theropods (including a Tyrannosaurus that actually looks the part, at least by 1970s standards), and even a stunted Rhedosaurus in tribute to Shea’s obvious inspiration, Ray Harryhausen.

As in many Harryhausen films, Planet of Dinosaurs put most of its resources into its nonhuman cast, but in this case the people are more stilted than the models, resulting in some awkward and unintentionally hilarious dialogue. This is no Beast from 20,000 Fathoms or Valley of Gwangi, but its best moments spark a similar joy. Aside from having the best beasts of the Spacemen & Dinosaurs canon, Planet of Dinosaurs is also unique among these films in that the astronauts don’t blast off to safety after their initial adventure; they remain on the dinosaur planet for years, maybe even the rest of their lives.

With the release of the CGI-reliant 65 this year, the chronology of Spacemen & Dinosaur movies is also a history of special effects in miniature (no pun intended), and there’s an iteration for every preference of low-budget spectacle. These movies are always cheap, often poorly acted and shot, and universally destined to circulate on YouTube, Tubi and bargain-bin DVD. But they are rarely altogether boring – at least for too long – and, like the feathered dinosaurs that hop and fly among us today, they’ve endured.

———

David Busboom is a writer and academic editor. His first book of short stories, Every Crawling, Putrid Thing (JournalStone, 2022), includes several dinosaurs.