Manufactured Ends

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #161. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

What’s left when we’ve moved on.

———

This is a column about media objects and the past. So why am I writing about Covid?

With Joe Biden’s choice to end the public health emergency on May 11, and more locally to me NY state’s decision to stop requiring masks in medical settings, those who need to avoid getting Covid are seeing any support rapidly narrowing. As this piece from January points out, many disabled and immune-compromised people feel left behind by these decisions, as they’ll remove essential services like free PCR testing (where it still exists), kick millions off of Medicare, and make essential medical trips more dangerous. At the same time, the end of the emergency also means the end of Covid tracking, the method by which the CDC determines (in theory) if masks should be mandated— if there’s no data, there’s no possibility to recommend a mandate.

As the podcast Death Panel pointed out in December when discussing the removal of federal mask mandates in 2021, policies like these, enacted co-constituently between federal and state governments, manufacture an end to a crisis that is undeniably ongoing. At the time I’m writing this, nearly 400 Americans are dying of Covid every day, over 30,000 this year already, a number which does not capture any of the disease’s non-acute effects. Clearly, it is not over with us.

So, I’m choosing to write about this for the column because I can see the US government, the CDC and other bodies around the world trying to turn the pandemic into the past tense, a project which has been ongoing for two plus years. As many disabled activists have pointed out, this is a decision which will lead to even more debilitation and death. Pushing back against it in the venue I have and trying to share some of the information I’ve learned as I’ve paid closer attention to the changing science and epidemiologists’ recommendations, feels appropriate.

In contrast to the CDC and the US government’s manufactured end date for the health emergency, there are still reminders of it everywhere, from persistent coughs to old signs requesting you keep 6 feet of distance. Masks are one of the most singular visual reminders of the ongoing pandemic, and for that reason they also elicit a lot of emotion. As this NY Times article argues, collectively many of us not only want to be done with the pandemic, but forget its worst moments ever existed: from the start, “as soon as solutions were put in place, we seemed to forget the problems had even existed; our sense of “normal” reset to assimilate them.” We have no national day of mourning for the millions of people dead; we have no systematic help for the tens of millions disabled. We’ve chosen, societally, to forget.

I recognize that in this column, I’m asking you to travel back into a place which may seem like it’s in the past but is in fact ongoing, a fact which is potentially angering and sad. In this light I’d like to say two things up front, starting with this: though it has implications for the safety of others, wearing a mask is not a moral signal but an action in support of public health. As outbreaks in the past have shown, moralizing illness and the spreading of illness is dangerous. While it’s a win for public health to prevent the spread of disease, getting sick can’t and shouldn’t be a reason for shame.

The second thing I want to say here is that I’m not perfect or immune to the desire to go back to normal. I’ve taken risks like flying, and I have gone to indoor gatherings, though I wouldn’t do that right now. There was a period a little over a year ago when I did go to some indoor events with no mask, and believed a lot of the official messaging – that Covid was almost over, that the vaccine was sterilizing (it’s not), and that individual risk was low. The results of those choices – I fucked around and found out, you might say – have convinced me to adopt more cautious behavior, as have new developments in medical research that suggest Covid is worse than we’ve considered it in the past.

Because my behavior has changed – I went to indoor events, and now I don’t – I’ve had a lot of people ask me why that is. Simply, it’s because I learned new information and decided to change my behavior because of it.

One of the things I found most helpful when I was recovering last year and worried about the long-term state of my body was the sentiment that while the best time to resume precautions might have been yesterday, the second best time is now. If you’ve stopped wearing a mask, you can start again at any time. And if you’ve been sick once, the best thing you can do for your health is to avoid getting sick twice.

Now that I’ve laid out my reasons for wanting to write this column, here are the four reasons I still wear a mask and encourage you to do so, too.

Protection for Immune-Compromised People

I’m an immune competent person (presumably, anyway – I’ll get to that in a second). But I have people I love who are immunocompromised, and who are at higher risk than I am of getting very sick in the acute phase of Covid as well as having complications later. This is one reason I was relatively plugged in to the science around Covid in 2020. (Another reason is that I spent way too much time on Twitter, which, surprisingly, is where a lot of epidemiologists hang out.) It’s also a major reason I wear a mask, and practice additional mitigations like precautionary quarantine when I visit these people. It’s important to me to do everything I can to keep them safe.

It’s also true that I will interact with immune-compromised people who I don’t know are immune-compromised. It’s just going to happen. It’s impossible to tell someone’s medical history just from looking at them, and no one should have to tell me about theirs in order for me to change my behavior. In the absence of that information, I believe wearing a mask is the most respectful choice.

Covid may be Immune-Suppressing

Studies in the past year have suggested that Covid does not only make you sick, but makes you more likely to get sick in the future. Several studies have suggested Covid suppresses immunity both in the acute stage and in the 8 months following infection, and possibly longer (since those studies only lasted 8 months). While researchers don’t yet know how often immune suppression occurs, even a small percentage of cases from a disease as widespread as Covid could be devastating on a societal level. So, when I said I’m immune competent a few paragraphs ago, what I really mean is that I was immune competent before I got Covid – and many people reading this might be in the same boat as me.

Building on this, Covid in the acute phase – meaning the first few weeks after you get sick – has the potential to cause adverse effects, even if you are vaccinated. It has been linked to increased risks of serious conditions like heart attack and stroke. Studies show that this risk increases each time you catch it. With over 90% of the population of the US having had Covid at least once, chances are if you’re reading this, you’re trying to avoid not just infection, but reinfection. As I said above, the best thing you can do if you’ve been sick once or more than once is try not to get sick again.

Long Covid is Prevalent, and has Lasting Effects

This is another major reason I wear a mask, and the one I try to spend time talking about with people who ask me about my mask. The CDC estimates that 1 in every 5 people who catch Covid will go on to develop Long Covid, an estimate that’s remained stable since at least 2021. As a recent example of this, it was confirmed that 16% of people in North Carolina – 16% of the entire state, 1.6 million people – have had Long Covid. And as far as we know, though vaccination keeps you out of the hospital quite well, it only slightly reduces the chance of developing Long Covid.

Long Covid is a name for a constellation of nearly 200 symptoms (which this study does an effective job breaking down). These include systemic multiorgan issues, brain fog, GI symptoms, tinnitus, and many more. They also include higher rates of susceptibility to conditions like diabetes and dementia. Many Long Covid patients develop dysautonomic disorders like POTS and ME/CFS, both of which themselves carry symptoms like fatigue and tachycardia, and both of which can be caused by post-viral issues. Patient accounts confirm that even those conditions that might seem negligible at first can be difficult, and even traumatizing; likewise, receiving appropriate diagnosis in the first place can be difficult. And even after receiving treatment, almost 71% of people with Long Covid have difficulty returning to work for 6 months or more, studies included in this NYT article show.

While a recent study suggested that symptoms resolve for some patients after a year, it has been criticized for making this claim based on doctors’ records and not patient reporting – many patients stop seeing a doctor not because their symptoms are resolved, but because the doctor hasn’t been able to help. The takeaway from this is that, especially in a U.S. healthcare context, many people are not getting the care they need, and illnesses like Long Covid are still getting pathologized or attributed to anxiety. In other words, if you do get sick, you shouldn’t count on the healthcare system to have a solution for you. Wearing a mask is protective against not just acute disease, but all these ongoing issues.

Wearing a Mask Aligns with My Values

This is the kind of statement that could be framed as identity politics: I perform an action because of how I want to be seen. However, I feel it’s important to say because I believe being a leftist means resisting structures that disenfranchise others, and in the context of a continuing pandemic, wearing a mask accomplishes this.

I have skipped a lot of leftist events in the past year because they’ve not required masks. Alternately, I’ve attended several which either did require masks or were held outside; I found these really emotional and felt a solidarity that I haven’t felt in other situations. When researching leftist responses to Covid I’ve learned more about the AIDS epidemic and political responses to it. Activists pushed against stigma, emphasizing that being sick should not equate to dangerousness or immorality, but also advocating for prophylactics like the barrier method and access to STI testing. These activists are a main reason things like condom distribution programs exist today. In other words, they emphasized collective actions, but also individual ones.

Additionally, part of being a leftist is critiquing structures of power and treating them with some level of skepticism. The recent response to the derailment in East Palestine, Ohio, has been to muse that the government’s insistence that residents are fine to return is motivated by a desire to minimize the accident, when just a few months ago several Democrats voted to quash rail unions that raised the danger of events like this one. When it comes to Covid, though, it seems like many people are ready to take the US government’s advice at face value. I believe this is an oversight. The U.S. response to Covid has overwhelmingly been motivated by a desire to get people back to work even when conditions are unsafe. In this light, Covid is a workplace safety issue and a labor rights issue, and it’s one the government seems determined to ignore from now on.

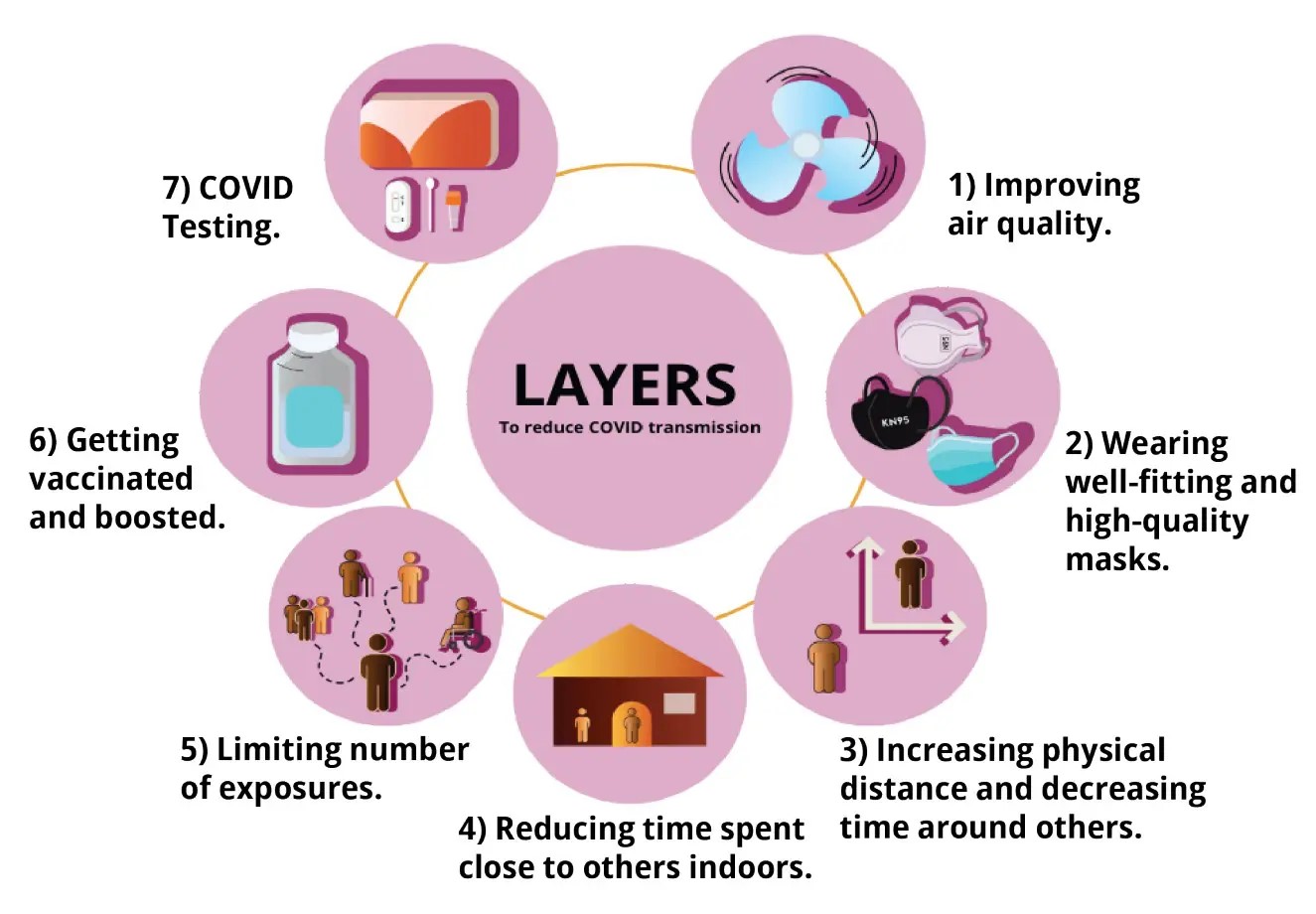

Lastly, I want to acknowledge that there are variations in privilege as to who can avoid public contact, and even who can wear a mask without harassment. Though I’ve intentionally organized my life to include hybrid work and avoid cramped indoor spaces, this choice is also a privilege: I was able to find jobs in my field that are hybrid, I haven’t (yet) needed to be back in person full time. But the thing that makes me advocate for universal masking despite this point is that everyone is safer when everyone masks. Masks are one of what the People’s CDC calls “layers of protection” for individuals and in groups: more masks mean less virus in the air. If you can’t mask or avoid public spaces, you’re safer in this environment too.

So, What Now?

The fact is that mandates work, not all the time or for everyone, but enough to increase the standard of living for vulnerable people. Without them, we get exactly the response that we’re seeing now: people assume that they are safe, because there would be rules in place if they weren’t, and then they get sick while doing what they’ve been told is safe to do. Personally, every week last fall was full of people I know, love, and work with reporting that they were sick, as has this spring. Even as careful as I am, I have close calls all the time. The system we have currently which has set us up to get seriously sick every few months, something we can’t afford financially or health-wise, is clearly untenable.

Frequently, I feel frustrated, scared and concerned. There are several bright spots that I hold when I feel this way. One is the development of nasal vaccines that (scientists hope) may provide sterilizing immunity, making the virus less transmissible. Advancements like this make it possible for me to believe that rather than taking the precautions I take forever, I’m actually waiting until further progress is made and trying to avoid getting sick as much as I can until then. Another bright spot is all of the people I know who adjust to my level of safety by eating outdoors even when it’s cold, testing before we meet and especially changing their behaviors to wear a mask when they’re out in public. If you’re someone I know who’s done these things, this column is dedicated to you.

Among these individual changes, structural change is clearly important. Part of the reason we are where we are is that the CDC has given us misinformation about the efficacy of masks, how Covid is transmitted (yes, it’s airborne), and how long you need to quarantine for (the five day quarantine, by the way, is the result of lobbying by the airline industry, not science.) However, as individuals we have the power of choice. We don’t need to go along with this incorrect information, and we have a lot of power to change our immediate situation right away.

Along with wearing a mask, here are a few resources I would suggest for keeping yourself and others safe:

- The People’s CDC has a Covid rate tracker and guides on how to gather safely and what to do if you get Covid

- I buy my masks from Bona Fide masks (NIOSH certified) and from distributors listed on 3M’s website. For the newest variants, an N95 or better offers you the best protection, but consider at least a KN95.

- If you can’t afford to buy quality masks, these services offer masks for free:

- At least for now, HRSA lets you search for pharmacies near you that may have free N95s

- Twitter-based mask distribution:

- Wendi Muse on Twitter (includes a link to donate)

- Maskup412 (local to Philly)

- Mandate Masks US has information about mask distribution programs as well as info about mask advocacy and COVID prevention efforts

If you read this whole thing, thank you. I hope it inspires you to put a few mitigation tools you might have set aside back in your toolbox, especially masking. And to return to what I said at the beginning, Covid and its effects, and public health in general, are inextricable from the environment in which we do critical work. I started my freelance career during the pandemic. Over the past three years I’ve had many occasions to think about why a particular project matters, against the horrific backdrop of everything that’s happened. If you have felt this way or are currently, I see you. All I can say is that I hope things are better soon, and I take comfort in knowing I am doing my part to protect myself and others in the hope of a better future where my work can feel more meaningful. I hope you’re able to do the same.

———

Emily Price is a freelance writer and PhD candidate in literature based in Brooklyn, NY.