Almost All About Eve

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #160. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Interfacing in the millennium.

———

There’s a part in Eve Babitz’s Slow Days, Fast Company where Eve, upon gatecrashing a social gathering by prominently necking with a friend’s glamorous Italian girlfriend, is confronted by her on-again-off-again partner, Shawn:

“Maybe you really like women better,” he suggested. “Maybe that’s been it all along.”

“But what does one do with women?” I said, imagining at once exactly what one would do. “It was probably just the Santa Ana,” I said.

“You never kissed me like that,” he replied.

She then goes on to muse about the senseless existence of the heterosexual paradigm:

[…] It’s a wonder that women have anything to do with men at all, and no surprise that they have devised all kinds of schemes to bind women to them, like not giving them any money. If you had your choice of sleeping with a beautiful soft creature or a large hard one, which would you pick?

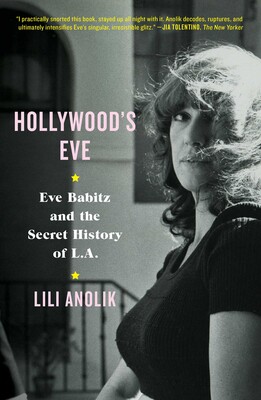

Her memoirs (and fictionalized-nonfiction, as every “novel” she wrote was more or less based on her own life) are littered with such remarks, in which she weighs the love of men and the love of women against each other in frankly honest terms before sighing, shrugging her shoulders, and going out to glamorously liaison with one or the other. She was flagrantly, cheerfully, and simply bisexual. Imagine my surprise then, upon reading the as yet sole book about her life, Hollywood’s Eve by Lili Anolik, that her biographer did not seem to have noticed this.

Anolik isn’t the only one. Since Eve’s “revival” in the twenty-teens she’s been venerated as a sexy, self-aware, liberated woman who slipped between the cracks, famous more for sleeping with Jim Morrison and playing chess nude with Marcel Duchamp than for her incisive, clever writing. The frankness with which she talked about sex and seduction has turned her into a hip, relevant name in an era of increased social awareness and mainstream feminism.

Biography is an imperfect art, of course, and there’s a lot to respect about Anolik’s attempt. She’s certainly not embarrassed by her personal investment in her subject. Her research on Eve’s personal history was able to match fictionalized characters with real names with impressive accuracy. The biography itself is a stylistic commitment remarkable in its bravery; it verges on memoir, refusing to separate Anolik the author from Anolik the woman, whose obsessive pursuit of Eve bordered on violating. Eve also blurred the lines between reality and fiction; Anolik’s forthrightness feels in the spirit of Eve’s compulsively honest writing style.

But when there’s such commitment and research invested in a project, it becomes perplexing how fundamental aspects of a subject’s life can slip through the cracks in such a way. Eve had many affairs with women, which she talked about candidly. Similarly, many of the male partners that she felt closest to were also bisexual – she refers to Shawn, her sometimes-partner through Slow Days, Fast Company, as “[lumping] all love together,” quite similarly to her response to Anolik’s anguished protest of, “But Eve, you’re straight!”: “Darling, I love everybody.” It’s telling that she runs to Shawn after her frustrating experience with Day, a woman she was interested in, and William, a longtime friend she emphatically wasn’t interested in – after a drunken hookup between the three of them, Day took up with William, not Eve. She goes to his apartment the next morning and mourns: “How could she, Shawn, have gone with William when I wanted her?”

Anolik spends the duration of her biography attempting to model herself on Eve’s confessional style. She instead more closely resembles Day, the beautiful, blind object of affection who comes close enough to Eve to touch but still misses the point, and sends her, reeling and furious, back to a person who understands her. The fact that, in her cast of the story, she is Eve makes the difference even more pronounced.

This is what is crushing about the heterosexual reimagining of Eve. She is deified by legions of trendy heterosexuals without any regard for the truth of her experience: that she was bisexual and writing about a particular and underrepresented facet of the queer experience, that of the chameleon. She was a different creature to the men she spent time with and the women; she was a different creature to straight people, whose games she was very good at playing, and other queer people, with whom she sensed a kind of preternatural kinship that she could not always even name. This is the paradox of bisexuality: it’s Eve’s earnest embrace of the fun and games of heterosexual showmanship that makes it feel so slippery to claim her as a queer elder, as if the fact that she appears to be something she’s not makes it true. But who better to embody that contradiction than Eve, who earnestly wrote about how Los Angeles “doesn’t like news, [it] likes artifice.” It never seemed to bother her to be taken at face value.

Why, then, does it bother me? The concept of bisexual erasure has been beaten into the ground; some inherited guilt of our proximity to heterosexuality seems to curse us into being concerned, above all, about perception, about how people see us and interpret us. It’s fascinating that Eve can seem so distanced from and so close to that topic all at once. Her writing is deeply personal, intimately concerned with her relationships with people; though she freely called herself “selfish” and “shallow,” her connections with the people around her were key to her life, her source of energy and of joy. She wrote about them to share them with people. To flatten these relationships – or, to be less accusatory, to not understand the depth of them – seems cruel. Eve may not have cared about how she was seen, but she clearly cared about how she saw the people around her. She had a palpable, physical joy at the time she spent with her friends and lovers, with people she met only a few times and with people she spent great expanses of her life with. Read any of her work and her love sinks through the story.

Anolik begins by describing her biography of Eve as “a love story”. Perhaps this is why it feels blinding to realize, mere pages from the end, that her understanding of Eve’s love is so limited. She mimics Eve’s expansive definition of love without comprehending it. It’s especially alienating because I, as the reader, felt like she was missing something obvious that I had no trouble understanding – but that, again, is the queer condition, that elemental perception of our existence that connects us and excludes others, that sent Eve running back to Shawn after her horror at the fundamental disconnect between her and William and Day. Eve’s deft navigation of the trappings of heterosexuality could trick the untrained eye, but it never changed her at her core.

Of course, there’s no end to this. I don’t claim to be any less biased than Anolik. Biography is never truly nonfiction. An author claims, to whatever extent, to have stepped back from their subject, and succeeds at that claim or doesn’t. The reader then either takes their word as truth, or doubts the author’s research or intentions or skill and consequently disbelieves. Anolik’s biography is not a failure because of her personal blind spots, it is simply an incomplete work. In much the same way as every translation is a betrayal, every biography is a portrait, capturing the likeness of a person but not their true face. Eve painted her self-portrait through her fiction, Anolik’s portrait of her muse through her memoir-biography – and as I read them I begin to paint as well, a picture that looks something like Eve, yes, but also something like me.

———

Maddi Chilton is an internet artifact from St. Louis, Missouri. Follow her on Twitter @allpalaces.