A Ride Through the Objective Field of Passion

This is an excerpt from the cover story of Unwinnable Monthly #160. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

![A map of Disneyland handed out to park visitors on July 17, 1955. Presented in black and white, Disneyland suggests they "take home this map and color it after [their] visit to Disneyland."](https://unwinnable.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Timss.jpg)

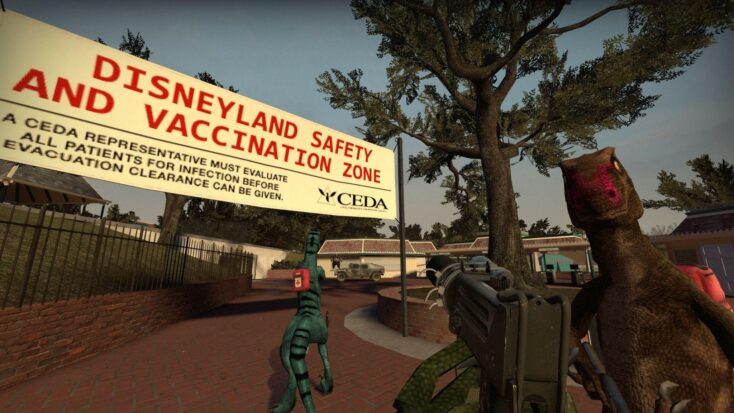

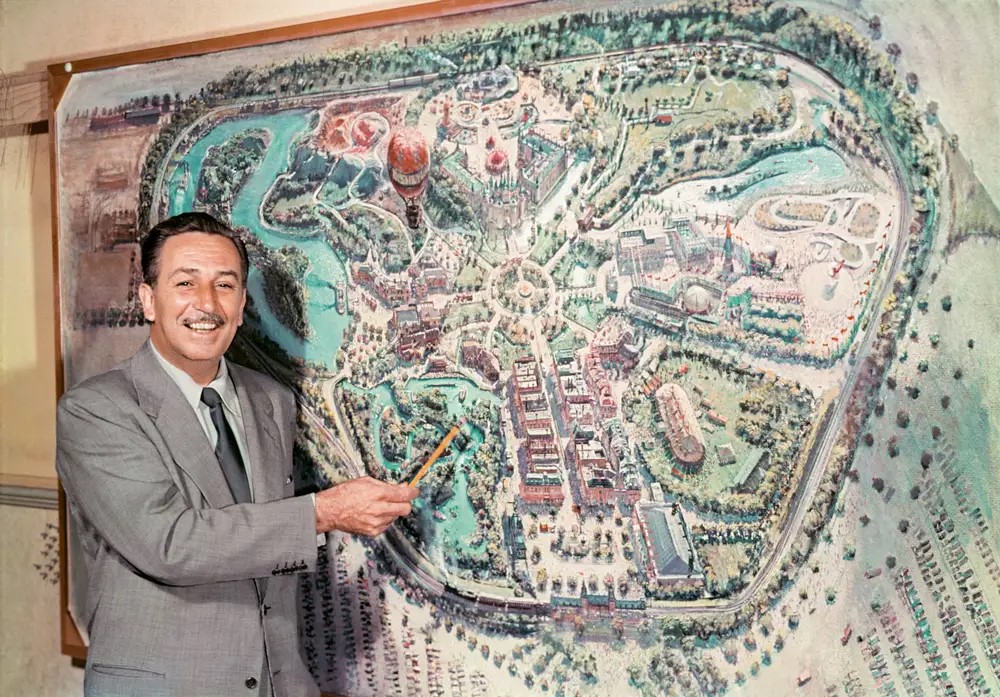

In the opening cutscene we barrel down Harbor Boulevard moving south on a mission to crash the front gates of Disneyland. Our tails clip through the bottom of the van dragging on virtual asphalt the entire ride there. Just outside the exit to Splash Mountain, along the banks of the Rivers of America, a helicopter is set to touch down and deliver us from the dangers of Southern California’s zombie hordes and mutants. It is for this reason that there are pistols resting in our talons and medkits stuck to our scaled hides. Such is the situation we find ourselves in the opening mission of the Left4Dead 2 custom campaign, and virtual recreation of Disneyland theme park, titled Journey to Splash Mountain, by mapmaker Dives.

This was the Summer of 2021 when three friends and I went wandering through Source engine custom maps every week, coated with as many model-swaps as the engine could put up with. Over the terrain of various virtual spaces we followed the flickering signs of our passion, one after the next, as drunks down alleyways and streets paying no heed to property law or any particular destination. I was in grad school then, playing games and studying theory with hopes of alighting upon ways that videogames continue, update or break with the political projects of 20th century avant-garde movements. What put it all together for me was seeing a friend of mine, appearing as a raptor from Jurassic Park, tossed through the bandstand at the center of Main Street USA, and then pummeled to death against the side of a police vehicle by a tank mutant roaring at us to leave his swamp, Scottish-like and reskinned to appear as Shrek, while “All Star” by Smash Mouth played over my speakers.

It is in this collision of intellectual properties and images of martial law, cartoon ducks, Americana and the atomic family, that we rediscover the efficacy which creative appropriation and play afford the critique of the spectacle of modern capitalism, a critique articulated throughout the 1960s by the Situationist International. A simple observation lies at the heart of Situationist works, theoretical texts like Society of the Spectacle or their involvement in the student protests of May ’68, which is that our subjective experience of time is affected by the construction and our use of the immediate environment in which we spend everyday life. It was, they noticed, through “the development of the urban milieu,” of modern cities like Paris, which saw its avenues widened in the 19th century to prevent rioters from erecting barricades, that power produces the alienated subject of “the capitalist training space” whose temporal perception is dominated by a logic of production and corollary consumption. The transformation of the city, as such, can be understood as the object of a veritable Situationist science.

Across its fifteen years of activity, the SI tested its theories for charting “the objective field of passion” through which we experience the immediate environment we live in and applied their findings in the construction of momentary ambiances, or situations. This was the group’s radical solution for provoking the passive subject of capitalism into playful participation with forms of life which capitalism cannot endure and so must suppress. It was by expanding the field of play over the whole terrain of life, through the transformation of churches into haunted houses and lecture halls into barracks, that the Situationist International conducted its revolutionary project for the liberation of temporal experience. In the movement’s foundational text, one of its key theorists Guy Debord perhaps said it best: “something that changes our way of seeing the streets is more important than something that changes our way of seeing paintings.”

The theories of the Situationist International attain a contemporary application in the creation of mods and maps like Journey to Splash Mountain. In its remarkable fidelity paid to the real Disneyland, this set of five levels betray its creator’s technical skill and aptitude for apprehending the spatial ideology of the theme park as a level designer’s means to craft emotional experiences and control a player’s course of movement. What Journey to Splash Mountain critically underscores in its appropriation of what has been acknowledged by designers like Chris Totten as the theme park’s “experientially rich architecture” are the theoretical principles that the design of videogame levels and urban spaces have in common. Here we can appreciate the object of the Situationist critique of urbanism at work in both real and virtual space: “Architecture does actually exist . . . it is a production coated with ideology but real . . . whereas urbanism is comparable to the display of publicity around [products] – pure spectacular ideology.”

Real architecture as level geometry. And level design as ideology. We came to understand this distinction at the rope-railing queue outside of Temple of Doom. Though virtual, because it obstructed our movement, it was obviously made of real architecture. Yet, as was demonstrated when some of us chose to jump over the ropes while others instinctually navigated their raptors through the queue instead, the invisible ideology of space is something different from real architecture. It was in this sense we came to appreciate how the adventure over the ropes differs from the adventure through them.

Disneyland is such a place where one can fall backward from the future to the frontier days of the American westward expansion without the slightest struggle, physical or cognitive. The prevailing logic of movement here is smoothness. A ubiquity of modern amenities and places to spend money ward against feelings of dissonance as guests navigate what popular culture scholar Shelton Waldrep calls the “nationless space,” where “borders are replaced with a temporal stage between the eventual capitalist takeover of the world and the pseudoreality of current late capitalism.” When, or wherever, one chooses for the setting of their day trip at Disneyland, it is as though the same adventure is taking place: a strolling journey over the paved avenues in the valleys beneath the painted mountains or under the green shade of canopies, always on the way to the next store, photo spot, show or ride queue. Unimpeded progress toward interchangeable destinations. In the canon of spatial narratives, adventure and quest fiction, the story of Disneyland is rather banal.

———

Braden Timss is a writer living in Seattle, WA. He’s lately graduated from Western Washington University with claim to an MA in English Lit. These days he has taken up playing board games and learning to make Quake maps using the world’s greatest level editing software, Trenchbroom. He wants to be a teacher, so mostly he just drifts. Follow his work on his personal site and on Cohost.

You’ve been reading an excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly Issue 160.

To read the article in its entirety, please purchase the issue from the shop or sign up for a subscription to Unwinnable Monthly!