Catharsis through Carnage

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #153. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Analyzing the digital and analog feedback loop.

———

The DOOM series contains perhaps one of the most serene game experiences you can get. I’m not saying that to be a contrarian; that’s just the facts. Despite the game being about ripping and tearing your way through various hellscapes this iconic first-person shooter is (paradoxically) pure escapism and catharsis. The 2016 soft reboot and DOOM Eternal in particular were designed to optimize a player’s sense of flow and, as the YouTube channel Screen Therapy points out, the latter offers the player a power fantasy set in a world that bears little resemblance to our own. In other words, players can take a break from their daily emotional labor. But these aspects of the Doom series, I’d argue, have been in the core design from the start, perhaps even before that.

Both John Romero and John Carmack, as explored in David Kushner’s biography of the two creators Masters of Doom, started out in hostile or overly controlled home situations that inspired them to find creative release at all costs. As a kid who was battered by his military stepfather, young Romero was a huge E.C. Comics and MAD magazines buff, and between learning how to program computers would churn out violent yet darkly comedic comics to cope. Romero would also listen to a lot of heavy metal, particularly Judas Priest, Metallica and Motley Crue.

Carmack turned to a mix of homebrew Dungeons & Dragons campaigns and computer hacking to reconcile his pent-up frustration at his mother’s efforts to railroad him into a career path she chose for him. Carmack was so passionate about hacker culture that he learned how to chemically engineer bombs (thermite paste) using his science class knowledge. With said paste, Carmack and his friends attempted to grab some of the Apple II machines from his school. The failed burglary landed him in a juvenile home at age 14. While the Two Johns’ early exploits are more extreme, especially in Carmack’s case, what’s clear is that their desire for escape from their oppressive daily lives growing up was intense. Equally clear is how their creative backgrounds fed into their eventual landmark FPS title.

Although this series is one that has always been on the periphery of my gaming life and one that I can’t see myself playing, it’s also one that I’m very fond of for the aforementioned statement. The original 1993 entry was one of the first games my family ever owned, one that changed our perspective of digital worlds and how they could be formally represented.

DOOM is also a title that tops what my dad calls his “relaxing twitch game” list (others included are Destiny 2, the Mass Effect trilogy and Dark Souls II). I think we all have at least a few of this type of game in our collection that we inevitably return to (for me, this is nearly every Devil May Cry entry or Soul Calibur VI) for some mindless, or even mindful, fun. Games from the Doom series are a good example not just of how therapeutic action games can be, they are examples of how we don’t always find solace in typical media genres or forms.

This experience is similar to how horror or thriller films offer a bounded experience that alleviates some people’s anxieties (basically me watching Candyman, 1992). As much as a lot of us (including me) love games that can fall under the increasingly popular and valid categories of “cozy” or “wholesome,” sometimes the best mindful games are the ones that resemble the golden age of edgy comics and rock music. Javy Gwaltney once made an astute observation that escapist media, no matter what form it takes, is often dismissed as “‘dumb’ entertainment” despite there being a real art to creating experiences that enhance flow. And, whew, do we ever need more flow (or at the very least some balanced escapism) in our lives right now.

Since I’m not exactly in a position to comment much more on DOOM beyond this point in my train of thoughts, I decided this month to pass the mic to my dad, an OG Doom fan who’s still into the series today. What follows is an informal interview with him. I tried my best to keep his answers more or less how he gave them. Some of his memories differ from how I remember the game as a kid (although to be honest, I don’t remember a lot except for the creepy flesh walls that would give me nightmares), but what stayed consistent over time is the effortless ability the game had to make you feel excited, powerful and sometimes even scared (but in a cathartic way).

What did you think of DOOM when you played the 1993 version for the first time?

I was extremely surprised I’d be into it in the first place. In the original you’re a space marine on a base, and for whatever reason you wake up after hearing screams and you can’t find anybody. The game opens you up and you hear [the] sounds bit by bit. The further into the maze-like environment [you go], the more powerful the creatures are.

It actually hooked me; I loved the fact that you became more powerful as you go along.

I was new to games. And I was surprised at how genuine the cosmic horror portrayed in the game was. [For example,] you run away from a creature in one area and you keep hearing but not seeing them when in a sewer section. The end of the game included an elder god-like creature that throws every creature you’ve already fought throughout the game. The creatures piled up around you.

At the end of the game you also find the BFG and you’re strafing back and forth during the final battle. Using all the techniques you’ve built up throughout the playthrough. [You use] your environment to your advantage. When you finally kill it [the final boss], then you get the music.

You build up the narrative in your mind, [but there was] really no story.You discover where your fellow soldiers have gone to; [they’ve become] zombified.

How has your relationship to DOOM changed over the years? Has it changed much?

[With the] Current DOOM games, a lot of the cosmic horror is gone. But the speed play and the [relentless rhythm] of the game pulled me back in. [The] Music fuels you.

You could just go in for a quick run. You could also search for hidden things. DOOM Eternal brought in some lore and that’s what kept me going. It was all about the environments, and how the atmosphere was still comic-book like.

What’s the most relaxing thing about DOOM 2016 and DOOM Eternal for you?

Speed and the choice of how much you want to engage. You don’t have to commit a huge amount of time to a campaign, if you don’t want to.

Does the concept art and the music of the recent games play into your sense of escapism/catharsis?

Yep.

Do you have any specific memories of DOOM that have always stuck with you?

The whole thing became [about] cosmic horror for me.

The soldier is away from the [moon] base, when he comes back he discovers literally all hell has broken loose.

I used to play in front of our bookcases at the dinner table.

* * *

When he mentioned this my memory was abruptly jogged. People passing by outside our apartment in the Beaches neighborhood of Toronto would hear the soundtrack and my dad’s reactions to the game from the open windows. He remembers them looking up at him with curious expressions from the street. It was probably the same way people looked up at me from the street when I was excited over reaching Rainbow Road for the first time or my sister when she would ride Epona around Hyrule Field for hours. Or later on, in a different home, when my mom defeated a dragon for the first time in Skyrim. Yes, we’re a family of unabashed geeks.

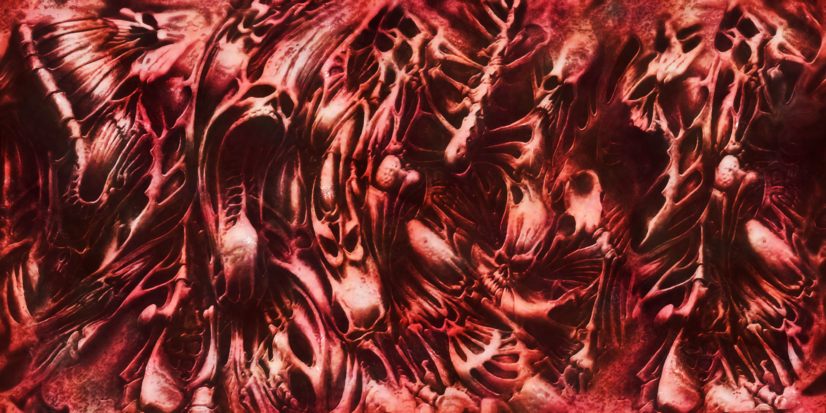

I wouldn’t often tune into the game, as I found it too gory for me, but some details as I got older made me smile. Like the little cartoonish head of DoomGuy as he’d throw glances about and learning what BFG stood for. In recent years, I’ve come to love a lot of the elements of DOOM, including the concept artists leaning into the body horror and rusty reds of certain Zdislaw Beksiński paintings. And considering how much Beksiński’s art influenced heavy metal culture this was a smart design choice. Dad and I agree that the concept art of DOOM alone could generate a whole other discussion of how, despite the series being intentionally low on narrative content, the concept art always did a lot of heavy-lifting with regards to environmental storytelling.

DOOM permeates game culture in a lot of different ways but I’d love to hear less talk about how hardcore it is and more talk of how it’s a game that’s brought a lot of people some much-needed relief. Yes, the games are often set in a hellscape . . . but it’s your hellscape to rip and tear through until it is done.

———

Phoenix Simms is a writer and indie narrative designer from Atlantic Canada. You can lure her out of hibernation during the winter with rare McKillip novels, Japanese stationery goods, and ornate cupcakes.