Cheap Machines

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #151. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

What’s left when we’ve moved on.

———

When I was in college, I spent a year writing posts for free for an online magazine. “Free” is, of course, an editorialization: I was paid in exposure, the recruiter promised, and every week someone on our team would win $20 if their post got the most views. I edited maybe a hundred articles that year and wrote something like twenty. I got the $20 once.

Around the same time, my friends and I would do online quizzes while we hung out during another friend’s radio show. Their results were often wildly divergent from their content: how many exotic fruits you can name, for example, determines what Oscars fashion you are, or what member of a pop punk band you should date. It was almost impossible to find a particular quiz; instead, we would always browse the homepage during songs and pick whatever caught our eye, accompanied by the background noise of Lady Lamb or Wavves or Jose Gonzales from the speakers. Despite their idiosyncrasies, and their clear composition by real people, the quizzes often felt a little empty, unfinished, lacking something. As much as they made us stifle a laugh while someone introed the next song, I couldn’t help the sneaking suspicion that the same thing was happening in my articles, too. How long would this material last? Who, exactly, was it for?

Kathi Weeks argues in The Problem With Work that the contemporary American labor landscape is disconnected from normal modes of production based on need. “Dreams of individual accomplishment and desires to contribute to the common good become firmly attached to waged work, where they can be hijacked to rather different ends: to produce neither individual riches nor social wealth, but privately appropriated surplus value.” It is not surprising that writing might be especially susceptible to fictions about being inherently meaningful. It exists primarily as an intellectual pursuit, partially because it’s supposed to be meaningful (you do love what you do, right? Your work means something to you . . . right?). However, as any philosopher of labor could tell you, the divide between intellectual work and physical labor can’t be so easily severed. The word “labor,” a Latin homograph that meant both to work and to slip, gestures at a totality that serves both intellectual interest and physical effort: for preindustrial cultural workers, “writing [was tied] much more concretely to the craft, skills and materials needed to produce a text as physical object” (Knapp, The Middle Ages at Work). It’s less a trajectory of progress, and more a cultural shift, that has led us now to think about writing as an abstract, intellectual affair. It’s also true that different kinds of writing require different kinds of physical exertion. Anyone who’s ever written on a deadline can tell you this.

Labor that’s optimized to no end is also, potentially, labor that can be replaced by machines. After all, writing is just a matter of putting words together in a particular order. Computers already scrape text from other websites to create “new” articles with the same content; at the same time, rushed writers compile text from other places and pepper it with original thoughts, to make an assemblage that looks like it could have been created by an AI. Recently, though, a friend of mine mentioned in a conversation about work that employers will never replace most workers with AI, because “then the company becomes responsible for the upkeep of the machines – now, the workers have to maintain themselves outside of work hours, and the company isn’t responsible for their health.” I think about this as I look at SEO posts which look like they were written by robots but are more often than not coming from human hands. In this race to produce content, can humans and machines even stay separate?

This question is equally as fraught in another arena that tends to be associated with pleasure and ease, but that is just as capable of being exploited. As games studios float the lure of crypto and NFTs, many more have already found another way to capture an audience by paying players to play, creating stashes of virtual currency that can then be traded in for real life cash. Games promise that they will become a valid source of income, while at the same time drawing people into debt with gachas and microtransactions. Even when they don’t provide monetary incentives, success in pay-to-win games can be made to feel very materially significant; Tony Tulathimutte has referred to mobile game Clash of Clans as “not just a war simulator played on your phone but a success simulator played on your life.”

In contrast, narrative games tend to view indebtedness more metaphorically, and be more interested in investigating what, exactly, it means to be in debt to something or someone. By simulating debt, at least as far as they are able, these games can use their interactivity to drive home its slipperiness, the way it sticks around and is almost impossible to get rid of- whether monetary, familial or personal. One would think that in order to most directly make a commentary on predatory debt, these games would try to tell stories that very clearly intersect with reality. However, more often than not, the games that have been able to pin down debt most seriously are those that use conventions of surrealism , science fiction or even magical realism to do so. Using these speculative genres, these games propose a horror that lies within debt and the meaningless work meant to assuage it: that rather than being a neat system with a clear path to success, it is instead an unresolvable problem.

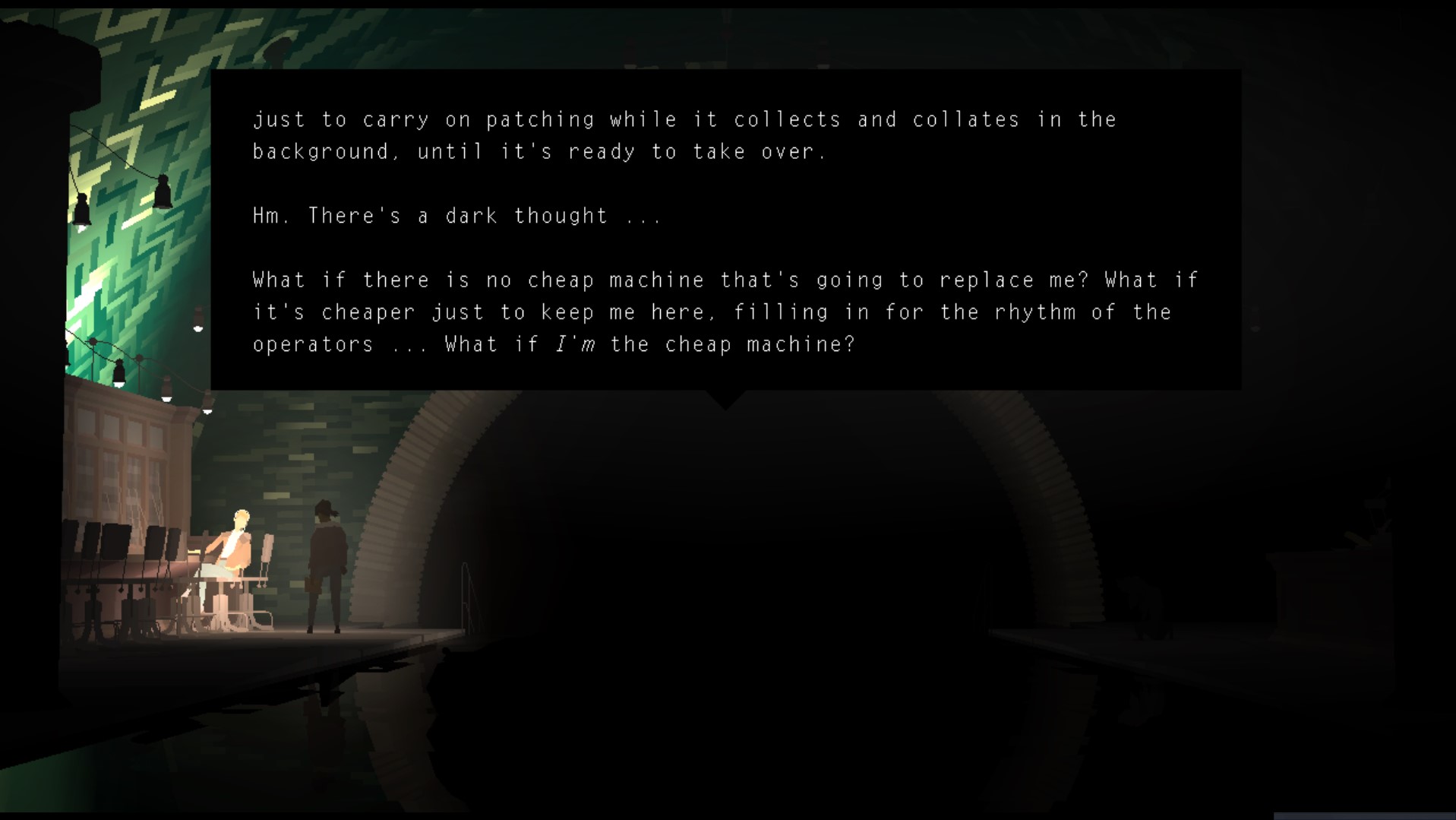

Speculative fiction and debt are by no means a new pairing, nor is their conjunction limited to games. A recent example is the TV show Severance, which is concerned with work and more indirectly with debt: specifically, with the idea that you could outsource your work, and therefore your suffering, to another “you”. I think also of the narrator of Charles Yu’s short story “Standard Loneliness Package”, who works for an “emotional regulation firm” that lets people transfer negative emotions to strangers, with the slogan “Having a bad day? Let someone else have it for you.”

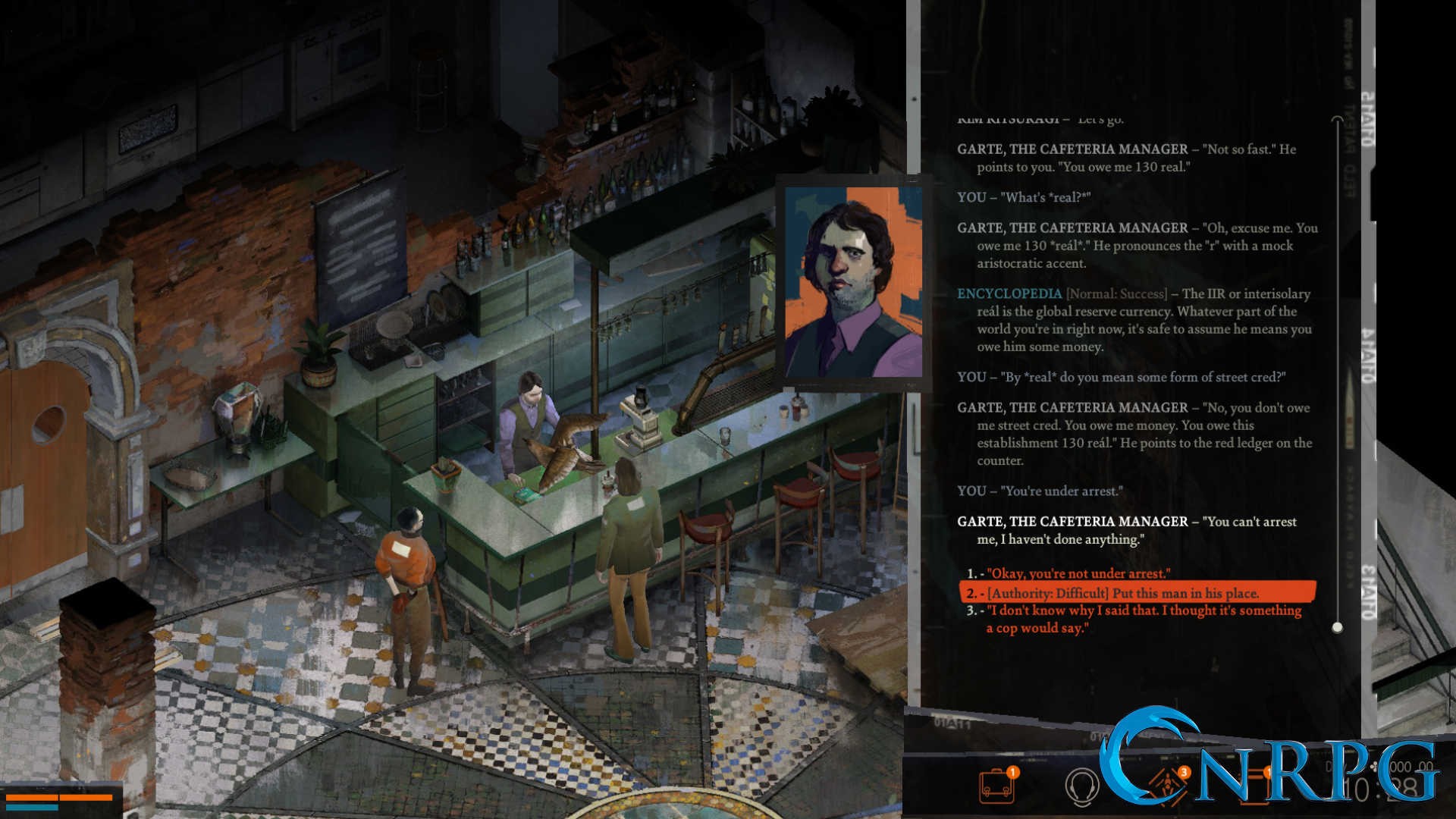

In the realm of games specifically, though, the effectiveness of commentary on debt comes from the fact that games, like debt, are supposed to have a solution. This feeling that you should be able to finish the task, cross off the checklist and move forward is so strong that it’s surprising, and emotional, when you’re put in a place where success is impossible. In Disco Elysium, for example, you are locked out of your hotel room by the manager for your disorderly conduct, as well as the fact that you owe over a hundred real, the local currency, in unpaid fines. Over the course of your first day, you’re instructed to collect the money while also trying to solve a murder. Your avenues for making money are limited: you can collect bottles off the street and sell them for 15 cents each; you can sell your clothes; or, if all else fails, you can beg a rich stranger for cash. Even if you do all of these things, odds are you’ll still come up short.

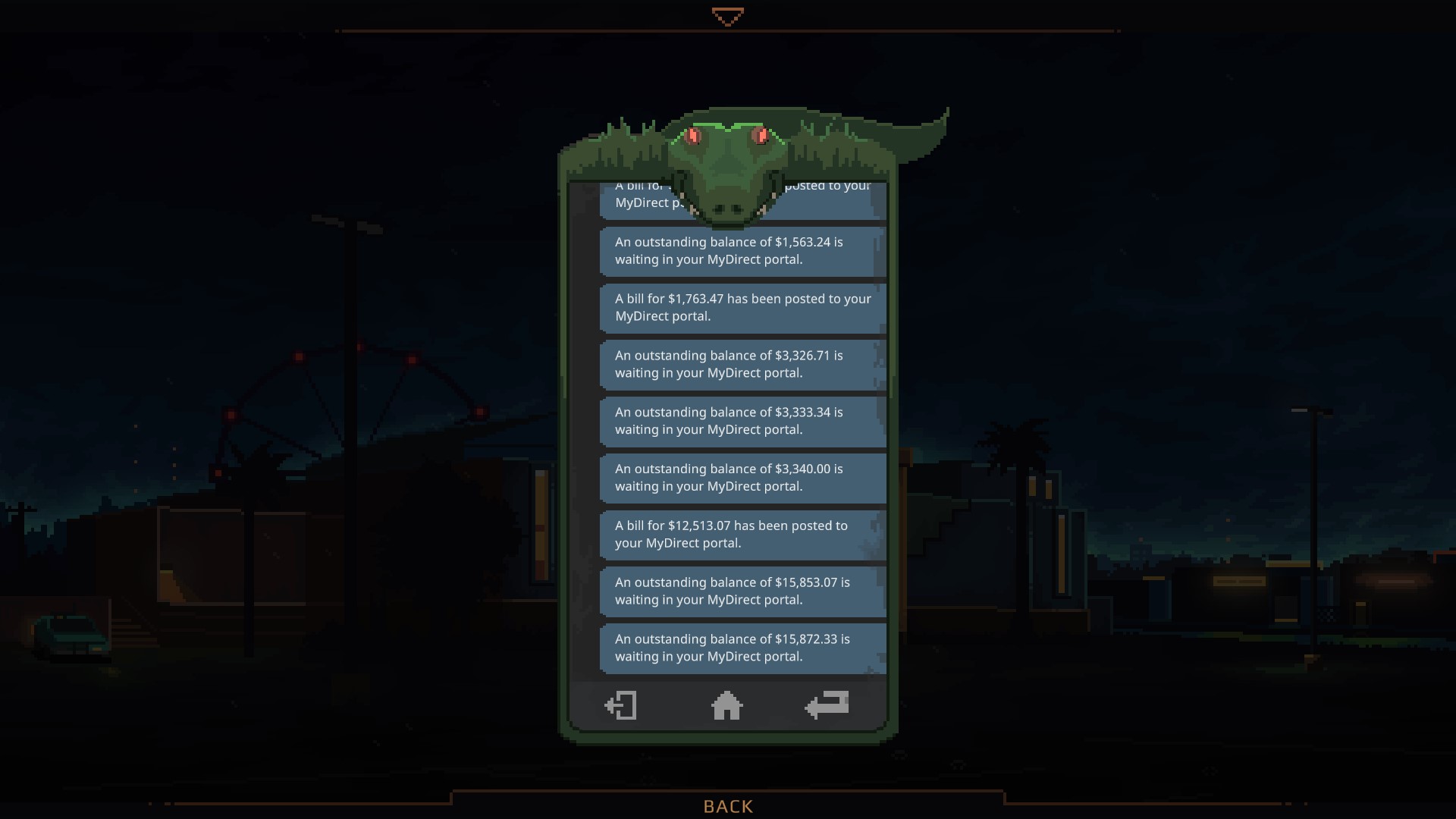

Recent text-based adventure NORCO also works to make your character’s debt omnipresent and unavoidable. Although your main character is returning to her hometown for the first time in many years, you spend much of NORCO with that character’s mother, a cancer patient and lifelong resident of Norco, LA. An early section has you navigating her to a warehouse to meet a contact through the mysterious app she’s doing gig work for, and her only route there is through a rideshare that drains money from your already scant savings. Over the course of the next act, ferried between a mall, a bar and the warehouse, I watched my bank balance slowly tick down toward zero. When I arrived at my last destination, I got a text from my medical provider: outstanding balance, 15k.

Part of the horror of gig work is that your body is the product and your labor might amount to little or nothing at all. I think about those SEO posts. I also think about talking with another friend in college who wasn’t allowed to sit down at her back-of-house job, because someone might walk in and see her. “No one ever comes in,” she said. “It’s just for the appearance.”

All of these games force players to engage, for at least a little while, in this horror: that the series of actions you perform will amount to nothing, that the main pursuit of your days is actually a finely tuned distraction from doing anything important. In their own individual ways, all of them use surrealism to paint an alternate but not necessarily hopeful picture. The only solution is to opt out, put down the phone, tare bag, steering wheel. But what about when we can’t?

And what about when we go into the realm of emotional debt – things owed, things unforgotten? This is something all these games dialogue with, too. In NORCO, you play as someone who is returning to her hometown reluctantly, and by extension to a network of people with claims on her she’d rather forget. In Disco Elysium, you are haunted by your ex, who you drove away in a non-specific but pathological way, a debt of emotional pain you can never pay off no matter how hard you try. In a different way, these problems are also about what happens when you end up with nothing where there should be something. How can you begin to repair the damage done- if you even want to?

Debt then, largely, is about an absence of choices, the foreclosure of possibility. What better way to demonstrate that than through an alternate reality where things could have been great, but really ended up much the same as they already are, if not slightly worse? The ride-share mystery game Neo Cab’s fluorescent-drenched purples and blues recall an eternal nightclub, energetic but sad, which we as the driver are foreclosed from ever entering. NORCO’s uncanny character illustrations convey longing, bitterness, and imbalance through wild eyes and hybrid machines that look like people, and vice versa. Kentucky Route Zero’s relationship to time is more uncertain, but characters’ conversations are usually oriented toward the past, with a few exceptions: at a resort called the Rum Colony, you can ask the main characters about their dreams. They want to date beautiful women, go on more exotic vacations, sit and listen to music. Mostly, they just want to rest.

This is the power of speculative fiction in games as a tool for exploring work and debt- as a way of reflecting back to us Weeks’s dreams and desires subsumed by capitalism, showing us, through play, how entrenched we are in trying to make our labor meaningful. This speculative imagining – when we imagine a world without debt, or waged work in general, what does it look like? – is clear across literary and political writings, but in games, its power comes from the player’s blunt and often unexpected interactions with failure. When you’re expecting to find a way to win, loss comes not just as a surprise, but as a frustration. By forcing players to encounter their own powerlessness, whether through narrative, gameplay, or a combination of both, you make them live for a moment in their own cycle of labor and all the indignities and inconveniences it entails. In forcing us to encounter our own identity as exploited workers, cheap machines, they also make room for us to ask – how could it be otherwise?

———

Emily Price is a freelance writer and PhD candidate in literature based in Brooklyn, NY.