Ashes to Ashes

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #146. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Architecture and games.

———

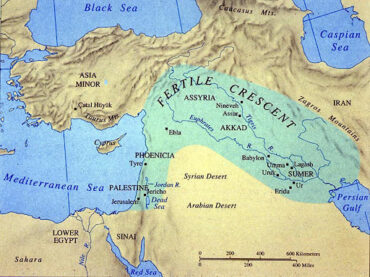

House of Ashes takes place during the search for weapons of mass destruction after the invasion of Iraq in 2003. The game follows a group of soldiers who stumble upon a temple which holds a dark secret. I know this all sounds hokey, but hear me out. When the roof collapses under their feet, the soldiers fall right into the middle of the temple, awakening a swarm of vampires. I’m probably making the game sound even more hokey, but stay with me for just a few more minutes. Wading through a literal blood bath . . . fine, I’ll just cut right to the chase. The temple dates to a few years before the destruction of the Akkadian empire by the Gutians at some point around 2150 BCE. Take some time to poke around the rooms of this building when you aren’t being chased by vampires and you’ll be richly rewarded. The temple contains beautiful examples of ancient artwork.

You might know that I’m an archaeologist by profession. I actually specialize in Egypt, but I’ve done some work in Iraq, so I’m familiar with the material culture in this part of the world. There have been some spectacular discoveries over the years. You can see a few of these in House of Ashes, along with a variety of other finds.

Akkad is usually seen as the world’s first empire, so the city has always fascinated scholars. Let me give you a brief history of the place. The location is currently unknown, but Akkad seems to have been situated between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers to the south of what would eventually become Baghdad. The city was pretty unimportant until a guy named Sargon came along. His origins are obscure, but Sargon wound up serving as the cupbearer to a king named Ur-Zababa in the nearby city of Kish. Bearing him a poisoned cup, Sargon assassinated Ur-Zababa, eliminating his family and usurping his throne. He then embarked upon a quest of world domination which he decided to call complete around 2290 BCE. There were a few dissenters, but he “smote them grievously.” His words, not mine.

Sargon was succeeded by his son Rimush after his death in 2279 BCE. Things went swimmingly as everybody learned to live with their new overlords. I’m of course kidding. There were constant rebellions in the region which brought on a bunch of brutal backlashes. Rimush was murdered by his friends a few years later, so his brother Manishtushu came to power. This guy was probably murdered by the same “friends” a few years afterwards. Manishtushu was replaced by his son Naram-Sin who took on the title “king of the four corners of the world” after he managed to finally suppress the various rulers of the region. Naram-Sin went about developing the economy, building all sorts of ditches, dams and canals. He created a system of standardized measurements and established Akkadian as the language of administration. Naram-Sin also seems to have declared himself a god. This was apparently the last straw for a lot of people because rebellions broke out all over the place towards the end of his reign. Naram-Sin died under mysterious circumstances in 2218 BCE. Shar-Kali-Sharri came to the throne, but he didn’t last long under the pressure of these rebellions. He seems to have fallen in battle against raiders from the Zagros mountains known as the Gutians. This caused the region to fall apart for about a century. “Who was king? Who was not king?” There was a priest who begged the question, but nobody seems to have known the answer.

You can see some wonderful artwork in House of Ashes including statues depicting the creatures known as lamassu and figurines in the form of the demon called Pazuzu. The game also features a variety of different stelae engraved with scenes of worship and war. The single most important artwork is the Mask of Sargon, though. Whenever scholars think about Akkad, this inevitably is what comes to mind.

You can’t miss the lamassu in House of Ashes. These are imposing statues depicting a divine being with the body of a winged bull and the head of a horned human. These protective creatures were often placed in pairs at palace entrances where they stood looking outwards. They’re what you call “double aspect” statues. Really examine them and you’ll notice that lamassu have one too many legs. This was meant to convey a sense of movement. When you see them from the front, they seem like they’re standing, but if you look at them from the side, they appear as if they’re walking. You can see really nice examples of lamassu today in Chicago, New York, London, Paris and Baghdad. The statues in House of Ashes look a lot like the ones in the Louvre. The only problem with what you can see in the game is that lamassu looked a lot more human around the time of the Akkadian empire. Lamassu at the time looked a little bit like birds. They only took on their final appearance about 1,000 years after Naram-Sin fell to the Gutians. What you’re looking at in House of Ashes would actually be Assyrian or Babylonian rather than Akkadian.

You pick up a figurine of Pazuzu at one point in House of Ashes. The characters make a passing reference to The Exorcist because the malevolent spirit in the movie is of course none other than Pazuzu. This demon king was depicted with both animal and human features. Pazuzu had the body of a human, the head of a lion, the claws of an eagle and the tail of a scorpion. Pazuzu also had some strange features like four wings and a coiled penis with the head of a snake. Your guess about this would be as good as mine. The creature was known for bringing mice during the dry seasons and locusts during the rainy seasons. While he was generally seen as being a bad guy to have around, people often called upon him to protect them from plague and pestilence. This would explain why there were so many figurines of him floating around. Pazuzu can be seen in museums all over the world, but similar to the lamassu, the figurine in House of Ashes looks a lot like a famous one in the Louvre. This dates to about the same time as the lamassu. But depictions of Pazuzu didn’t change much over time.

The stelae in House of Ashes are pretty representative of Akkadian artwork. There isn’t a universally accepted definition for this type of artifact, but stelae are basically just really big plaques. You come across quite a few of these in House of Ashes. The most remarkable thing about Akkadian artwork would have to be its focus on realism and this definitely turns up in the game. There are two things to consider on this point. People on the one hand have clearly defined features. Muscles in particular. Themes on the other hand are almost universally worship and war. The king was the key figure. He was frequently shown either accepting tribute or capturing slaves. The archaeologist Henri Frankfort famously called this a “grim world of cruel conflict.” He said that “man was subjected without appeal to the incomprehensible acts of distant and fearful divinities who he must serve, but cannot love.” This of course included the king. I haven’t been able to identify any of the stelae in House of Ashes, but if you want to see how they compare to the real thing, there are some great examples in Boston from the reign of Naram-Sin. Pretty much everything else from this period is in Baghdad.

The only thing in House of Ashes that definitely is Akkadian would be the Mask of Sargon. As you might expect, this dates to the reign of Sargon. Well, maybe. The majority of scholars think it belonged to Naram-Sin. This makes a lot of sense given the hack marks around the eyes. The assumption is that somebody really hated this thing and Naram-Sin was by far the least popular king. Whatever the case may be, the Mask of Sargon is a portrait in bronze of about a foot in length by eight inches in width. You can see the braided hair and beard that were so typical of Akkadian artwork. The artifact has always been called a mask for some reason, but what you’re actually looking at is a bust. The sides and back of the head are depicted. The artifact was found a few miles outside of Mosul in 1931. The piece was preserved in Baghdad until it was looted after the invasion of Iraq in 2003. While nobody knows where the Mask of Sargon is today, scholars aren’t very concerned because the artifact is famous enough that it can’t just disappear onto the antiquities market forever . . . they think. But you can see a really nice replica in Berlin.

While most of it doesn’t actually date to the right period, you can see some nice examples of ancient artwork in House of Ashes. This would mostly be Assyrian or Babylonian rather than Akkadian, but you have to cut the developer some slack because almost none of the latter has been preserved. You’ve basically just got the Mask of Sargon. Supermassive did what they could, which I think is more than enough given the circumstances. I mean, really, how often do you ever see this kind of stuff in a game? Hardly anybody has even heard of Akkad before.

The artwork in House of Ashes offers a look at an empire that once was mighty, but now has largely been forgotten. The takeaway here is that nothing lasts forever. Naram-Sin believed that he was a god, but these days nobody knows the first thing about him. Ashes to ashes. Sargon led his city to power and prominence, but nobody knows where to look for the place. Dust to dust. This seems to be what the game is trying to say about history. The past is nothing but a fading memory . . . unless vampires are involved. This changes everything. The past is pretty permanent when vampires enter the equation. I guess the moral of the story is not to go poking around in the desert for weapons of mass destruction when there’s a real possibility that you’ll come across a temple filled with vampires. In any case, try to just enjoy the ancient artwork.

———

Justin Reeve is an archaeologist specializing in architecture, urbanism and spatial theory, but he can frequently be found writing about videogames, too. You can follow him on Twitter @JustinAndyReeve.