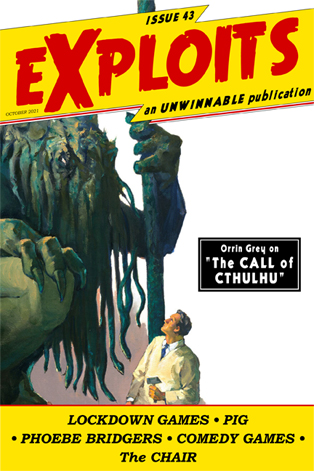

“The Call of Cthulhu”

This is a reprint of the Books essay from Issue #42 of Exploits, our collaborative cultural diary in magazine form. If you like what you see, buy it now for $2, or subscribe to never miss an issue (note: Exploits is always free for subscribers of Unwinnable Monthly).

This is a reprint of the Books essay from Issue #42 of Exploits, our collaborative cultural diary in magazine form. If you like what you see, buy it now for $2, or subscribe to never miss an issue (note: Exploits is always free for subscribers of Unwinnable Monthly).

———

I feel like a lot of people came to “The Call of Cthulhu” as their entry point for the fiction of H. P. Lovecraft in the days before Lovecraft was quite so much of a household name as he is today. This can probably be laid at the feet of the roleplaying game of the same name, which helped to popularize the story title so much that even Metallica lifted a (respelled) version for a song.

All of which is kind of a shame because, frankly, this is a less-than-ideal place to dip your toes into the writings of the Old Gent, finding Lovecraft in arguably his driest and most pedantic mode. Quite simply, “The Call of Cthulhu” is a story that should not work. The vast majority of its “action” literally amounts to a dude reading various papers, and it is guilty of almost all of the sins for which Lovecraft is often (rightly) lampooned, even by his faithful, from constantly telling you that things are scary rather than actually making them scary, to calling “indescribable” things that he then describes at great length.

Yet it’s one of Lovecraft’s best-known and most frequently reprinted stories for a reason, and it’s not just because it has his most famous creation in its title. Written in 1926, “The Call of Cthulhu” sits at the center of Lovecraft’s burgeoning mythos, a word that wasn’t associated with his work until well after the fact, pulling together threads that he had been toying with in previous tales.

Which is to say that, while “The Call of Cthulhu” may not be the best place to start if you’re largely unfamiliar with Lovecraft, it’s a story that you’ll arrive at, sooner or later. And when the time comes to pick up a copy of “The Call of Cthulhu,” whether it’s your first time or your hundred-and-first, this new one from illustrator Gary Gianni and Flesk Publications is well worth the purchase.

The chief reason is more than 100 new illustrations by Gianni, whose work hopefully needs little more introduction than Lovecraft’s does, but there’s something else going on in this volume, too. A detail tucked away in the copyright page, proclaiming that the text has been revised to “exclude racial terms.”

It’s a small enough thing, in theory, but for anyone who knows Lovecraft’s reputation as a particularly noxious racist, it’s a much bigger thing in practice. In this case, it actually tightens up the tale more than a bit – placing the focus of certain scenes where it always needed to be, rather than on old Howie’s prejudices.