A Dark, Dank Death: Blind Beast (1969) on Blu-ray at Last

“I want to pioneer the art of touching.”

Twice, recently, I have been tasked with reviewing films by Yasuzo Masumura, and have found myself writing around the only film of his I had ever previously seen, Blind Beast. Once, the disconnect was pretty profound – though acerbic as hell, Giants and Toys is a far cry from the depravity of Blind Beast. With Irezumi, however, the parallels were more striking.

Blind Beast is a film that I had been meaning to watch for decades, ever since I worked in a video store. It wasn’t Masumura’s name that let me know I needed to see it back then, though. It was more the name of the writer whose work the film is adapted from, “Japanese Poe” Edogawa Rampo.

Even that wasn’t really it, though. Rampo has, after all, been adapted to film numerous times – with more than 60 credits on IMDb – and I’ve seen hardly any of them. No, the real thing that tweaked my curiosity about Blind Beast was the reputation of the eponymous blind sculptor’s studio, a phantasmagoric funhouse of oversized female features cast in papier mâché. Breasts, sure, but also noses, eyes, ears, lips, and two giant reclining bodies, stretching the length of the room.

Knowing that the reveal of the studio was coming, and having seen stills of what it contains for years before I actually sat down with the film for the first time not that long ago, I was still stunned by the sequence in which we are first introduced to it. It is disorienting and eerie in a way that only films from this era seem to ever manage, while also feeling vastly ahead of its time.

An extremely weird and striking set will only go so far, however, even if the vast majority of the film takes place within it. Fortunately, like the other Masumura films I’ve reviewed recently, there’s more going on in Blind Beast than what it says on the tin. What begins as a conte cruel about a sculptor who kidnaps his “muse” gradually becomes something much more twisted and symbolic, as the two slowly fall into a relationship that is mutually self-destructive.

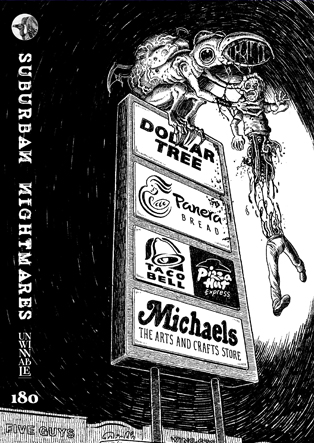

It is this that keeps Blind Beast from becoming the generic exploitation flick that its logline makes it sound like, even while it is probably also this that led a contemporary Variety review to call Blind Beast a “sick film.” In the booklet that accompanies the Arrow Video Blu-ray of Blind Beast, with a gorgeous cover by Tony Stella and lavishly illustrated with stills from the film, Virginie Selavy explores Masumura’s “complex idea of perversity.”

In several of Masumura’s films, she argues, “the perversity of deviant individual desire is pitted against the ingrained perversity of the oppressive, hypocritical social order. The outcome is never straightforward: although collective perversity is always excoriated, individual perversity in Masumura’s cinema is a double-edged sword, often simultaneously emboldening and degrading, liberating and destructive.”

Such is certainly the case in Blind Beast, where Michio, the blind sculptor, and Aki, his victim, find a kind of ecstatic liberation in the throes of their “new art of touching,” while at the same time devolving in a self-destructive, sub-animal existence. This is expressed through dialogue that reads a little like decadent poetry, a little like cosmic horror, as Aki compares their degeneration within the lightless studio to insects, amoeba, and jellyfish.

The film opens with images that suggest where it is headed. The first things we see are artful images of nude forms in bondage, credited in the film to a Mr. Yamana but actually filmed during a 1968 exhibition by underground photographer Akira Suzuki. Mako Midori, who plays Aki in the film, was one of Suzuki’s actual models, leading to a disorienting sensation of falling into a fictionalized world even from the opening credits.

Just about everything in Blind Beast is exaggerated, suggestive, symbolic, grotesque, subjective, and gorgeous. The fictional version of the photographic exhibition that kicks off the film is called “Les fleurs du mal,” named for Baudelaire’s famous book of poetry, itself scandalous and frequently censored at the time of its original publication.

In 1969, Blind Beast was likely shocking. Today, after more than half-a-century filled with films geared specifically to shock, it has lost much of its power to scandalize, but the “dark, dank” depths of its central abyss are still such that few other films since have dared to plumb them, for good or ill.