Notes on a Train Trip

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #142. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #142. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

The Burnt Offering is where Stu Horvath thinks too much in public so he can live a quieter life in private.

———

In March of last year, as the pandemic wrapped its hands around the throat of normal life, I ran a one-shot for the tabletop roleplaying game Call of Cthulhu for several Unwinnable contributors as a much-needed bit of escapism. That one-shot, as is often the case, stretched into several sessions. A second one-shot, which actually wrapped up in just one night, followed. Then a series of several more supernatural mysteries unfolded in the dark corners of Lovecraft’s fictional Massachusetts. There was the time with the thing in the lake next to the run-down motel and the other time where a dozen copies of the same antique dealer showed up for dinner and the one with the old lady and her totally normal dolls and a couple more besides. Spurred on by a desire to distance themselves from a string of mysterious arsons, the group decided they were up for a bigger challenge. They hopped on a steamship bound for London and, from there, they found horror on the Orient Express. Now, after a year of pell-mell two-hour sessions every Thursday, that journey is also coming to a close.

1.

Call of Cthulhu is a horror roleplaying game, originally released in 1981, that combines elements of whodunnit mysteries, pulp adventure and soul-searing cosmic horror. Scenarios generally break into two phases. During the initial investigative portion, players gather clues in hopes of unravelling the mystery. If they do a good job, those clues (usually) increase their survivability in the second portion, in which they confront the supernatural threat. Madness and death follow (in greater or lesser degrees), leaving the few survivors shaken but assured that the screaming, meaningless end of existence has been staved off, for a little while at least.

2.

Considering the high casualty rate and the bleakness of the subject matter, you might make two misjudgments about Call of Cthulhu. First: that it isn’t fun to play. I assure you; this is not the case. Most Call of Cthulhu games I’ve participated in take on a character similar to telling ghost stories around a campfire. There are scares, sure, but they are almost always punctuated by laughter. And even when laughs don’t feel appropriate, being scared is still entertaining in its own way – that’s the whole foundation of the horror genre, after all.

Considering the high casualty rate and the bleakness of the subject matter, you might make two misjudgments about Call of Cthulhu. First: that it isn’t fun to play. I assure you; this is not the case. Most Call of Cthulhu games I’ve participated in take on a character similar to telling ghost stories around a campfire. There are scares, sure, but they are almost always punctuated by laughter. And even when laughs don’t feel appropriate, being scared is still entertaining in its own way – that’s the whole foundation of the horror genre, after all.

3.

The second common misconception is that, like horror stories and movies that see their protagonists meet grisly ends, Call of Cthulhu should work best as single serve, standalone mysteries. And yet, Masks of Nyarlathotep (1984), a globetrotting campaign that spans hundreds of hours, is considered one of the best RPG campaigns of all time, in any genre. While no other Call of Cthulhu campaign quite reaches those lofty heights, many are nevertheless considered classics of the form.

While there is certain pleasure to seeing your character get eaten by a monster in the climax of a one-shot, Call of Cthulhu’s real appeal lies in their slow dissolution. Call of Cthulhu characters often start as weirdos and their exposure to corrosive alien knowledge serves to make them more so, and seeing that decline is never boring. Further, a long running game lets you pick your demise, to an extent. Death comes unexpectedly, of course, but just as often you can see it coming and drive into its gnashing teeth if you desire. A common quip is that you can’t call a part of Call of Cthulhu investigators successful unless, Ship of Theseus-like, none of the characters who were there at the start of the campaign survive to finish it off.

4.

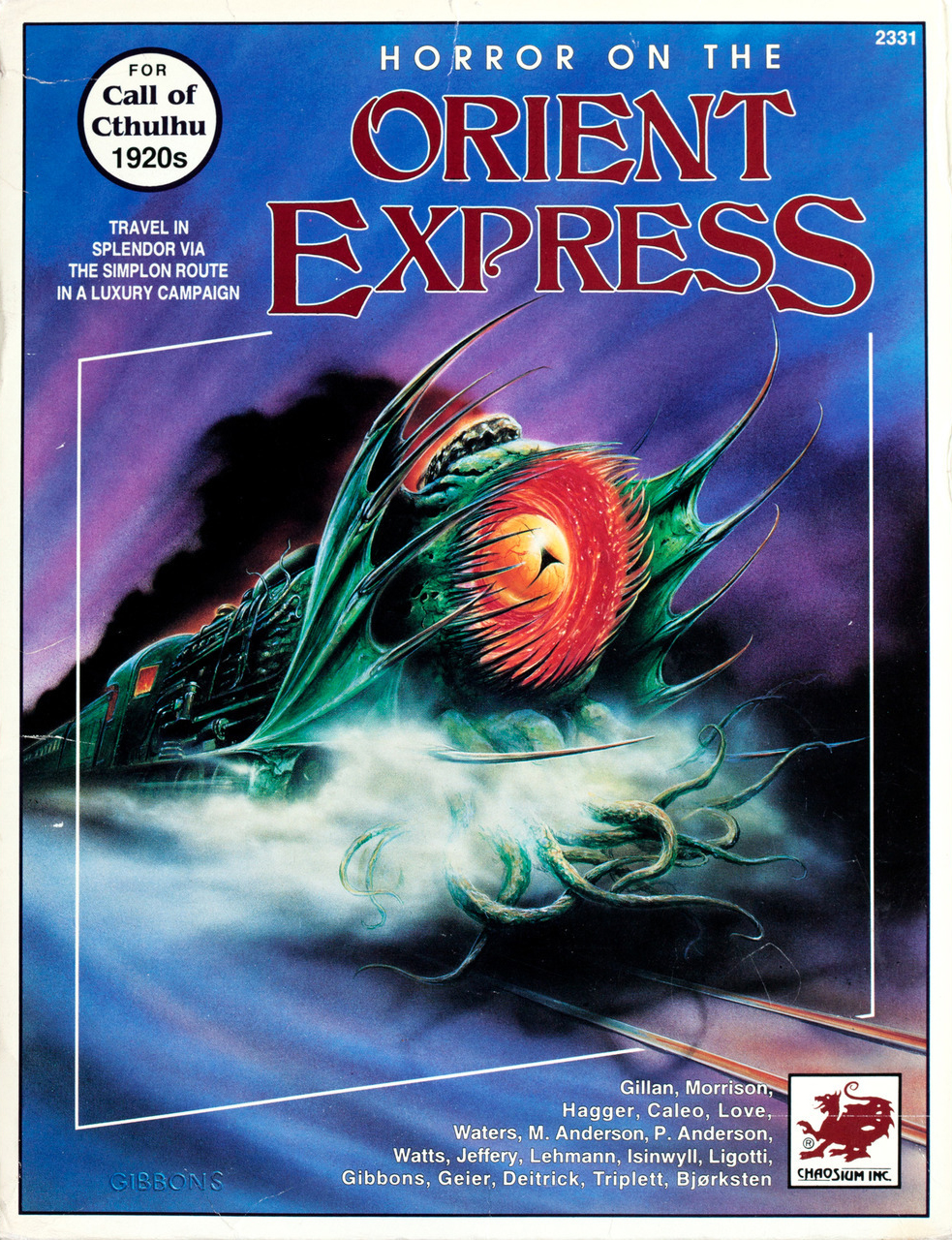

Chaosium originally released Horror on the Orient Express in 1991. It consisted of four campaign books, a book of interesting passengers and a sheaf of handouts crammed into a one-inch-thick cardstock box of dubious durability. In retrospect, it’s marriage of Lovecraft’s Cthulhu mythos with the historical mystique of the train line and its connection to Agatha Christie’s most famous novel was a bit of a lay-up, but at the time it felt ambitious and, compared to the other Call of Cthulhu campaigns on the market, unusual. (If you don’t want to know the various twists and turns of the plot, perhaps skip to the next column).

Chaosium originally released Horror on the Orient Express in 1991. It consisted of four campaign books, a book of interesting passengers and a sheaf of handouts crammed into a one-inch-thick cardstock box of dubious durability. In retrospect, it’s marriage of Lovecraft’s Cthulhu mythos with the historical mystique of the train line and its connection to Agatha Christie’s most famous novel was a bit of a lay-up, but at the time it felt ambitious and, compared to the other Call of Cthulhu campaigns on the market, unusual. (If you don’t want to know the various twists and turns of the plot, perhaps skip to the next column).

Still, my 13-year-old version was underwhelmed. It seemed a bit cut and dried, a bit too neat. The players are hoodwinked into travelling the length of the route, stopping at key locations to find pieces of an evil statue, the Sedefkar Simulacrum. The set-up offers players no real chance to see through the introductory ruse. A series of plausibility-threatening historical coincidences puts all the pieces in convenient reach of the Orient Express’ stops (why didn’t the cultists collect them decades ago?) and the scenarios that lead to them all seem rather linear, A-to-B affairs. While there are thematic links to the lingering aftermaths of the Great War and the growing strife in Europe throughout, each scenario is otherwise unconnected to the rest. Meanwhile, another series of convenient coincidences unleashes a secondary antagonist, a previous owner of the statue. That owner is, rather than a lunatic sorcerer or some unknowable entity from beyond space and time, a vampire. To 1991 Stu, this seemed a particularly dusty narrative choice.

What did I know, though? Horror on the Orient Express won two Origins Awards, one for Best Roleplaying Adventure, one for Best Graphic Presentation of a Roleplaying Game.

5.

Horror on the Orient Express sat on my shelf, unplayed, for decades. In 2014, a new, expanded edition emerged. The whole project was nearly derailed by a Kickstarter campaign over-burdened with tchotchkes, and accounting for those likely left the end product a bit less deluxe than perhaps was intended. There are some curious graphic design choices, for instance, the handouts are mostly unsexy (though the full color puzzle piece Simulacrum is a delight). But that box – three inches wide – is massive and filled with no shortage of new mysteries. The contents of the box never quite fit properly back inside after you open it (physically, but also metaphorically).

Horror on the Orient Express sat on my shelf, unplayed, for decades. In 2014, a new, expanded edition emerged. The whole project was nearly derailed by a Kickstarter campaign over-burdened with tchotchkes, and accounting for those likely left the end product a bit less deluxe than perhaps was intended. There are some curious graphic design choices, for instance, the handouts are mostly unsexy (though the full color puzzle piece Simulacrum is a delight). But that box – three inches wide – is massive and filled with no shortage of new mysteries. The contents of the box never quite fit properly back inside after you open it (physically, but also metaphorically).

Most of the chapters see a fair bit of additional polish and development. The theming – of the trauma of war, of totalitarianism, of the horrors of the body, of dismemberment, of people not being who you think they are – are made more explicit, to unsettling effect (there is no place for subtlety in a year-long campaign). The biggest change is a series of new scenarios sprinkled throughout. They’re musty old journals and tomes come to life, flashbacks with pre-generated characters, playing out events from the distant past. Most, but not all, reveal important moments in the life of Fenalik, the aforementioned vampire. His time as a Roman soldier, the circumstances surrounding his transformation, his scheme to gain possession of the statue during the Crusades. An entire additional book, Reign of Terror (2017), details how Fenalik, now posing as a nobleman in France, loses the Simulacrum on the eve of the Revolution. These flashbacks, no doubt inspired by the videogame Eternal Darkness (2002), are a compelling addition to the narrative, at once engrossing in their own right, a much-needed break from the main campaign and, because Fenalik is not the central villain, an elaborate red herring of sorts.

6.

I adore the 2014 edition. It was thrilling to read and the extra material made Fenalik work in a way that just didn’t come through for me in 90s. Using a vampire as a central villain in a Call of Cthulhu game is sheer genius. Bloodsuckers are simultaneously terrifying and utterly predictable. We know how they work and yet something about them makes them continue to be compelling, despite having been laid bare to the pop culture consciousness. Fenalik speaks to that. Because he exists in a game of cosmic horrors, because he covets a blasphemous, outré artifact, he doesn’t read as a cliched undead boogeyman. Instead, he comes off as a sorcerer, something that was once a man but has become corrupted by the arcane forces he wields.

But he isn’t a sorcerer. He’s a vampire. And if you meet a vampire without taking the proper precautions, you’re a lamb to the slaughter.

7.

Fenalik tore through my group. Having helped them from the shadows in restoring the sundered Simulacrum, its wholeness and its proximity drove him to attack them on the train in the middle of the night. About half of players had, at one time or another, hypothesized he was a vampire, but the notion never crystalized in the group at large and they were entirely unprepared for him. About half of them died. It was beautiful.

8.

A character’s agency is largely seen as sacred among tabletop RPG players. A character is, after all, an extension of the player and their primary means of interacting with the narrative space, so meddling with that relationship is inherently invasive. Relatedly, most players favor games that are arranged around rewarding that agency with lots of meaningful choices. Players want to be able to choose which way they go and, if they decide to go north, they also want some sense that should they have gone south, an entirely different series of events would have unfolded. Even if this is an illusion. If north is perceived as an inevitability, though, players chafe.

A game where all roads lead north despite the choices of the players is often referred to as being “on rails” and the game master running that game is “railroading” them. This is a natural reaction to the power differential in RPGs – the GM controls the world, the story, all the non-player characters and adjudicates all the player actions. If the GM takes the reins of the players’ choice as well, they become props and the game ceases to be a game.

9.

Horror on the Orient Express, a game with the name of a train line in the title, is very much on rails. In the original 1991 version, this is very much apparent and predictably chaffing.

Horror on the Orient Express, a game with the name of a train line in the title, is very much on rails. In the original 1991 version, this is very much apparent and predictably chaffing.

The 2014 edition adds even more constraints. The historical chapters, like time travel stories, demand that certain events remain unchanged, lest the facts of the present unravel. So, Sedefkar must die, Fenalik must not be killed, the statue must be dismantled and lost, and so on, while the GM must do everything in their power to ensure that these things occur as ordained. Even if that requires doing things players would normally deem unfair.

Something strange happens, though. My players seemed to have a kind of awareness that they were, to paraphrase Michael Moorcock’s term, sailors on the seas of fate. Sensing their doomed destinies, they concentrated on the small details of their character decision and often worked to ensure that the larger plot played out “correctly.” There were no hair-brained schemes to steal the Simulacrum or murder key NPCs in a bid to alter the future. Constraint, in this case, led to a kind of unspoken collusion and, with it, something like narrative freedom. Most of the time.

I think, in part, this is because Horror on the Orient Express offers a trade. In exchange for curbing the traditional freedoms of an RPG, the rigidity of the story allows for plot twists that resemble those crafted for more traditional stories, that are foreshadowed, supported by the narrative and yet leap out and surprise. With one exception (in which many player characters died in a largely narrated epilogue); I believe these twists have delighted rather than dismayed my players. I also think they will cast a long shadow on all our various future games, because no other campaign handles its narrative quite like Horror on the Orient Express.

10.

This may not be a usual reaction to the material.

This may not be a usual reaction to the material.

Our sessions are often a bit less that two hours in length, so they are often characterized by a sense of purpose: to have something happen, a great scare, a startling twist. I usually prefer my Call of Cthulhu games to sprawl, for players to waft around chatting with non-player characters, to only express a sense of urgency when in the thick of the horror. With this group, though, there is a willingness to trade freedom for results.

That makes sense, I think, for a game that came together as an escape hatch from a global pandemic. Perhaps, in this way, Horror on the Orient Express was the best choice of campaign, with its episodic forward motion careening on at ever greater speed, like a train, its whistle howling every Thursday night.

11.

The end is looming larger on the horizon. Just a little longer now before we find out if we’re coming up on a dark, endless tunnel, or if we’ve been in the tunnel all along and we’re about to see the sun.

———

Stu Horvath is the publisher of Unwinnable. He reads a lot. Follow him on Twitter @StuHorvath.