Rediscovering 24-Carat Black

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #134. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #134. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Selections of noteworthy hip hop.

———

I just did the math, and since I started this column in March of 2019, I have reviewed 105 albums. While this has been awesome in many ways, it is often also a bit overwhelming to start up the next month’s column. So this month, I’m excited to do something a little new. Instead of my normal album breakdown, I interviewed Zach Schonfeld, author of the new entry in the 33 ? book series on 24-Carat Black’s nearly forgotten masterpiece, Ghetto: Misfortune’s Wealth.

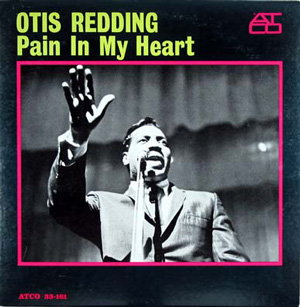

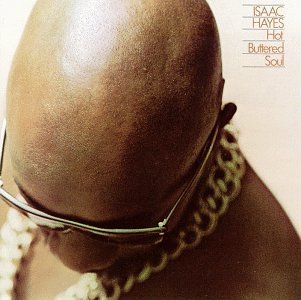

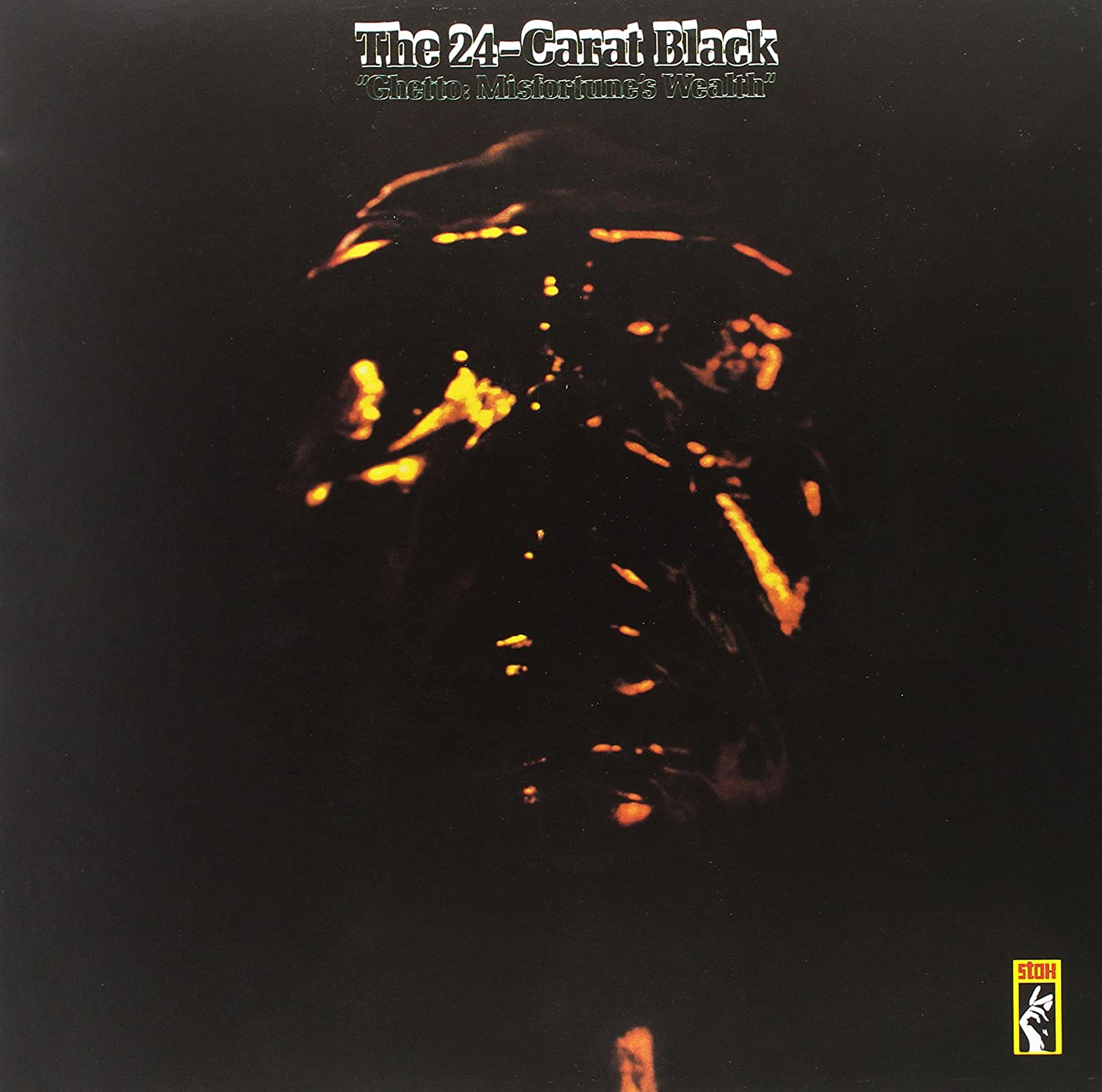

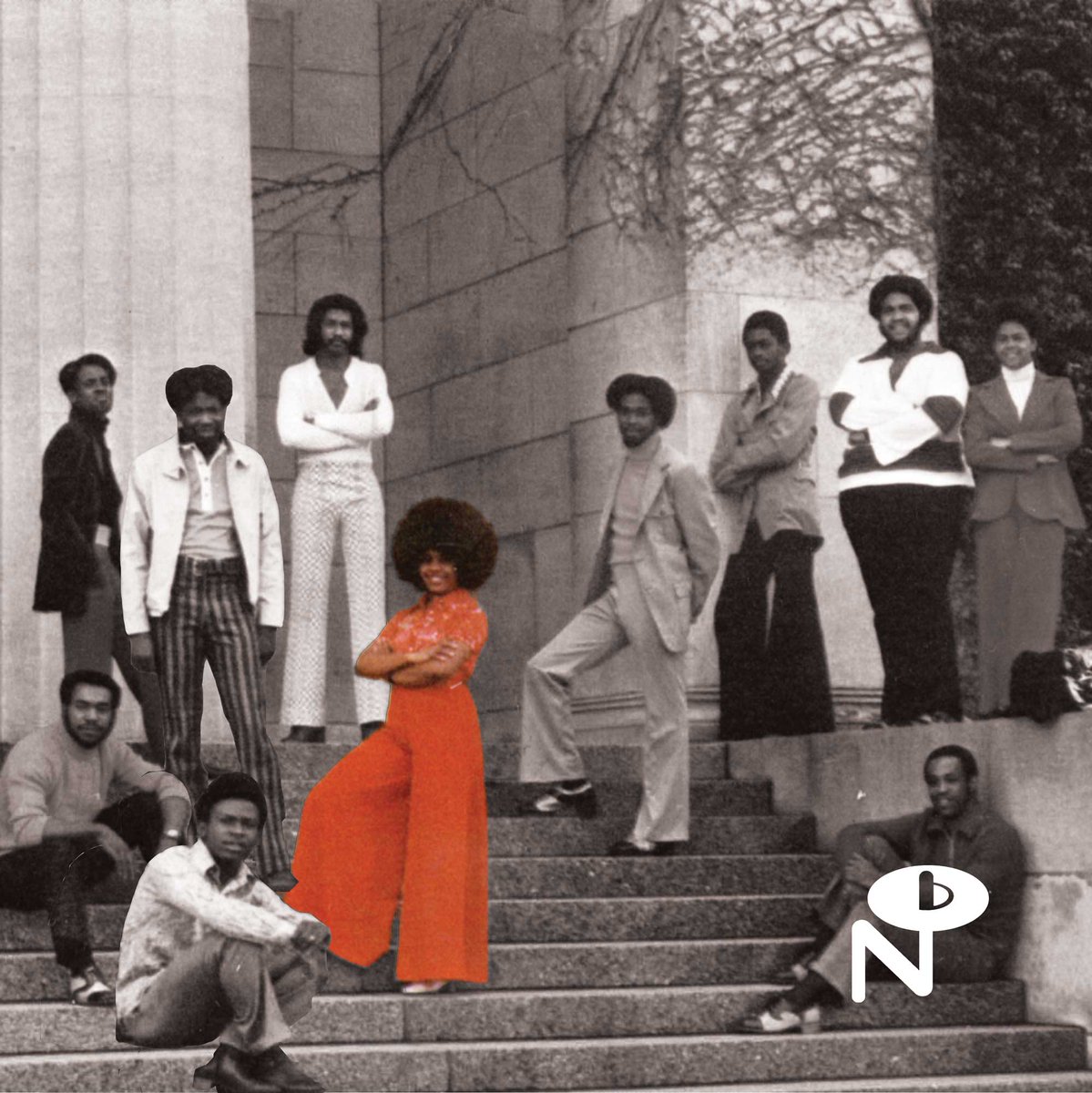

Briefly, 24-Carat Black was a funk/soul band founded in the early 1970s and signed to Stax records, home of (among others) Otis Redding, Isaac Hayes and The Staple Singers. The collective released one album in 1973, Ghetto: Misfortune’s Wealth, and then effectively disappeared. Fifteen years later, as hip hop was on the ascendancy, producers began digging through vinyl crates, looking for cuts to sample. By 2020, 24-Carat Black has been sampled by everyone from Ishmael Butler of Digable Planets, to Metro Boomin, to Kendrick Lamar and Kanye West. Yet, living members of the band have yet to see serious compensation for their groundbreaking work.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

N.S.: Can you tell me about the genesis for your book and what piqued your interest in this album specifically?

Z.S.: I’ve been really interested in sampling for a long time and my interest in 24-Carat Black grew out of my interest in sampling. I remember when I was first getting into hip hop in high school, I would be listening to some old record and I would recognize a sample that I had heard on a rap album or vice versa.

Z.S.: I’ve been really interested in sampling for a long time and my interest in 24-Carat Black grew out of my interest in sampling. I remember when I was first getting into hip hop in high school, I would be listening to some old record and I would recognize a sample that I had heard on a rap album or vice versa.

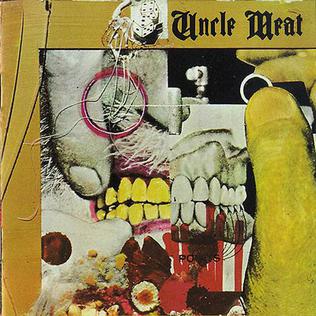

Madvillainy was one of the albums that first got me into hip hop and my dad is a huge Frank Zappa fan. I kind of inherited his interest in Zappa and there was this one short interlude track on Frank Zappa’s album Uncle Meat called, “Sleeping in a Jar.“ I recognized it from the Madvillain album, and that just blew my mind. My dad’s Frank Zappa CDs were the least cool thing imaginable and the fact that the hippest, most critically acclaimed indie rap album was sampling this weird interlude from a CD that I found in my dad’s record collection was crazy to me. That was one of those experiences that really piqued my interest in sampling, just the way that little snippets of music from the past could be resurrected and reimagined within the parameters of a completely new style of music.

Madvillainy was one of the albums that first got me into hip hop and my dad is a huge Frank Zappa fan. I kind of inherited his interest in Zappa and there was this one short interlude track on Frank Zappa’s album Uncle Meat called, “Sleeping in a Jar.“ I recognized it from the Madvillain album, and that just blew my mind. My dad’s Frank Zappa CDs were the least cool thing imaginable and the fact that the hippest, most critically acclaimed indie rap album was sampling this weird interlude from a CD that I found in my dad’s record collection was crazy to me. That was one of those experiences that really piqued my interest in sampling, just the way that little snippets of music from the past could be resurrected and reimagined within the parameters of a completely new style of music.

Over the years, I had noticed that this group 24-Carat Black had been sampled by a lot of my favorite rap groups. Digable Planets and Kendrick Lamar piqued my interest in checking out this album and trying to figure out what it was all about, but the immediate impetus for my Pitchfork story was the Pusha T album, Daytona, sampling of Tyrone Steels saying “infrared, you know what I mean?” [from the 2009 compilation album, Gone, released by the Numero Group].

Over the years, I had noticed that this group 24-Carat Black had been sampled by a lot of my favorite rap groups. Digable Planets and Kendrick Lamar piqued my interest in checking out this album and trying to figure out what it was all about, but the immediate impetus for my Pitchfork story was the Pusha T album, Daytona, sampling of Tyrone Steels saying “infrared, you know what I mean?” [from the 2009 compilation album, Gone, released by the Numero Group].

I kind of became obsessed with that sample and that inspired me to Google 24-Carat Black and find out what was written about them. I knew that they’d been sampled many times and I knew that the Ghetto album was interesting and unique, but I was surprised by how little had been written about them. The only really detailed account of their existence was based on interviews with members of the group for the liner notes for the Numero Group album.

N.S.: What was your initial reaction to the album from your first spin?

Z.S.: It really is a one of a kind album, and different from any other album that was released on Stax, which released a lot of amazing soul and funk albums, and a lot of albums that I love. I’m a big fan of Isaac Hayes and Otis Redding, and you know that’s amazing stuff. But I was struck by how dark and how desperate this album is. It has this darkness about it that really struck me, and at the same time it manages to be really funky. There are some jams on there that really go on and on, and hit you over the head with how funky they are. But it also didn’t sound like anything else I had heard in its combination of funk and soul tropes with more orchestral elements. I think this unique quality of the album is a big part of why it has endured and why it has inspired so many subsequent generations of artists.

Z.S.: It really is a one of a kind album, and different from any other album that was released on Stax, which released a lot of amazing soul and funk albums, and a lot of albums that I love. I’m a big fan of Isaac Hayes and Otis Redding, and you know that’s amazing stuff. But I was struck by how dark and how desperate this album is. It has this darkness about it that really struck me, and at the same time it manages to be really funky. There are some jams on there that really go on and on, and hit you over the head with how funky they are. But it also didn’t sound like anything else I had heard in its combination of funk and soul tropes with more orchestral elements. I think this unique quality of the album is a big part of why it has endured and why it has inspired so many subsequent generations of artists.

N.S.: I was immediately struck by how this just seems so perfect to be sampled because there’s these little loops that the album gives room to breathe, and it makes them ripe for the plucking.

N.S.: I was immediately struck by how this just seems so perfect to be sampled because there’s these little loops that the album gives room to breathe, and it makes them ripe for the plucking.

Z.S.: There’s also sort of a cinematic element to it. It has a lot of very lush orchestration that reminds me of the blaxploitation soundtracks of that era, and I can understand why rap producers are eager to bring that orchestral feel to their music. A lot of rap albums have kind of a cinematic feel, like an intro, an overture and skits. It makes sense that 24-Carat Black fits within that aesthetic.

N.S.: Tell me a little bit about the members of 24-Carat Black that you interviewed for this book.

Z.S.: To track down Princess Hearn, the lead singer from 24-Carat Black, I just messaged her on Facebook, out of the blue. She was very happy to have an opportunity to talk about the group and she was bursting with really amazing stories and memories about her time with them. Princess Hearn was also a real driving force for this book and helped me get in touch with a lot of the other members for the book.

I also interviewed C. Niambi Steele for the Pitchfork piece. She was very wary of me at first because as she told me, “I’m still living in poverty. My mom just died and I can’t afford to keep her house, and you’re telling me that Kanye West and Pusha T are sampling my music? I still can’t pay my bills.” I was able to convince her that I didn’t want to sugarcoat her story and I wanted to tell the brutally honest truth about the fact that she wasn’t getting paid for the samples. Eventually, I think I earned her trust and she and I had a very long conversation about 24-Carat Black and she slowly opened up. I think she recognized that I was sincerely interested in engaging with the brutal truth and the exploitation that are at the center of this story.

I even flew to Michigan to meet with Princess Hearn and her older brother Clarence Campbell. Clarence was one of the managers of the group, and he actually introduced the band to Dale Warren. He was very eager to tell his side of the story, and he felt his role in this album had never really been brought to life before. We sat in the living room of his house in Ann Arbor, the same room where he sat with Dale Warren almost 50 years prior, and he told me that that was where Dale Warren first decided to change the group’s name to 24-Carat Black. I remember, he left the room and went to some sort of storage space and he came back with an original pressing of the Ghetto album. He also drove me around Michigan, and gave me a driving tour of 24-Carat Black history.

I even flew to Michigan to meet with Princess Hearn and her older brother Clarence Campbell. Clarence was one of the managers of the group, and he actually introduced the band to Dale Warren. He was very eager to tell his side of the story, and he felt his role in this album had never really been brought to life before. We sat in the living room of his house in Ann Arbor, the same room where he sat with Dale Warren almost 50 years prior, and he told me that that was where Dale Warren first decided to change the group’s name to 24-Carat Black. I remember, he left the room and went to some sort of storage space and he came back with an original pressing of the Ghetto album. He also drove me around Michigan, and gave me a driving tour of 24-Carat Black history.

Just going to Michigan to meet with some of these people was fascinating. I also met with Tyrone Steels (the drummer) when I was there. We talked for hours. He was one of the founding members of the teenage band, The Ditalians, which later evolved into 24-Carat Black so he had the full story from the very beginning. He’s stuck with the group through all these trials and tribulations. At one point, I pulled out my phone and played him the Pusha T song that sampled his voice, and I asked, “did you get any money for the sample?” He said, “You know, I got a check for 60 something dollars.” His wife opened up a drawer and pulled out the check and said this is the only money we’ve ever gotten paid for any of the samples of this music.

N.S.: You have mentioned Dale Warren and he’s quite a character in the book. Could you talk about him a little bit?

Z.S.: Dale Warren was the composer, arranger and general mastermind of 24-Carat Black. Warren saw the Ditalians perform and decided to take this group under his wing and completely reimagine their repertoire, bring them in a completely new musical direction and rename them 24-Carat Black. He started his career as an arranger for Motown later he ended up at Stax Records, and was a really fascinating and influential figure in this era of funk music. He was a classically trained arranger and had this dream of fusing classical compositions with funk and R&B, and 24-Carat Black was his attempt to bring that vision to fruition.

Z.S.: Dale Warren was the composer, arranger and general mastermind of 24-Carat Black. Warren saw the Ditalians perform and decided to take this group under his wing and completely reimagine their repertoire, bring them in a completely new musical direction and rename them 24-Carat Black. He started his career as an arranger for Motown later he ended up at Stax Records, and was a really fascinating and influential figure in this era of funk music. He was a classically trained arranger and had this dream of fusing classical compositions with funk and R&B, and 24-Carat Black was his attempt to bring that vision to fruition.

But he was a complicated figure. Over the course of reporting this book, I interviewed a lot of people who knew Dale Warren quite intimately, including Princess Hearn who was married to him during the time of 24-Carat Black’s existence, and pretty much everyone that I interviewed about Dale talked about the fact that he was an alcoholic. He always had a bottle of Beefeater gin as he was working. He left his wife and young child to marry 18-year-old Princess Hearn. I interviewed his daughter who spoke very candidly about the fact that Dale was abusive to her when she was a young child. I didn’t want the book to gloss over the fact that this person was a musical genius and he was also an abusive alcoholic.

Dale Warren arranged the strings for some truly incredible records, including most of Isaac Hayes’s early albums and some of The Staple Singers albums from this era. He helped create some incredible music but I’m not sure very many people know his name today outside of the rarified circles of record collectors and soul obsessives. Because 24-Carat Black’s rise and fall was so intertwined with his own story, I feel like the first half of the book kind of functions like the most detailed account of his life that has ever been written. He died in the mid-90s, so obviously I wasn’t able to interview him for the book. He was a musical visionary and I hope that this book brings his story to life, because I think people should know his name.

Dale Warren arranged the strings for some truly incredible records, including most of Isaac Hayes’s early albums and some of The Staple Singers albums from this era. He helped create some incredible music but I’m not sure very many people know his name today outside of the rarified circles of record collectors and soul obsessives. Because 24-Carat Black’s rise and fall was so intertwined with his own story, I feel like the first half of the book kind of functions like the most detailed account of his life that has ever been written. He died in the mid-90s, so obviously I wasn’t able to interview him for the book. He was a musical visionary and I hope that this book brings his story to life, because I think people should know his name.

N.S.: I want to flip over to the other side of things and talk about the kind of hip-hop side of the book now. You got some really incredible people to chat with you. What was the process like for interviewing rappers and producers?

Z.S.: I wanted to really dig into the stories behind the samples. I feel like what gets lost a lot of the time when people write about samples are questions like, how did this producer stumble across this record, or, why did this record, speak to this rapper? When you’re talking about the 80s and 90s, there was no YouTube, there was no Spotify. If you were looking for records to sample you had to go out and you know really go crate digging and really dig in the most literal sense for cool and interesting records. I really wanted to do some real detective work to try and figure out how this record became such an underground phenomenon.

Z.S.: I wanted to really dig into the stories behind the samples. I feel like what gets lost a lot of the time when people write about samples are questions like, how did this producer stumble across this record, or, why did this record, speak to this rapper? When you’re talking about the 80s and 90s, there was no YouTube, there was no Spotify. If you were looking for records to sample you had to go out and you know really go crate digging and really dig in the most literal sense for cool and interesting records. I really wanted to do some real detective work to try and figure out how this record became such an underground phenomenon.

I interviewed Ishmael Butler from Shabazz Palaces and formerly Digable Planets numerous times while I was working on this project and he has such a great story about how he discovered the 24-Carat Black Album. His father was super into progressive funk and avant-garde jazz of that era, and Ish had a wonderful story about discovering the record in his father’s record collection and then going back and literally stealing it from him when he was working on the first Digable Planets album. I love how it embodies this idea of these records being passed down from generation to generation. I think that story probably spoke to me personally a little bit, because I also discovered a lot of great music just from digging through my parent’s records.

Another interview that I was really excited about was with the producer Hi-Tek who produced the Black Star album, which almost included a 24-Carat Black sample, but then he changed up at the last minute and the sample got cut. What’s crazy is that Hi-Tek’s father and uncle were both members of the Ditalians, but left the group before Dale Warren later transformed it into 24-Carat Black, and Hi-Tek didn’t know that his father was involved with this group until he was sampling it.

Another interview that I was really excited about was with the producer Hi-Tek who produced the Black Star album, which almost included a 24-Carat Black sample, but then he changed up at the last minute and the sample got cut. What’s crazy is that Hi-Tek’s father and uncle were both members of the Ditalians, but left the group before Dale Warren later transformed it into 24-Carat Black, and Hi-Tek didn’t know that his father was involved with this group until he was sampling it.

N.S.: Who’s one producer or rapper who didn’t talk to you that you wish you could have gotten? Who was your white whale that got away?

Z.S.: I tried really hard to get to talk to Eric B. and Rakim because their song “In the Ghetto” was the first major rap song to sample 24-Carat Black which kind of kicked off this trend. I kept emailing their manager and he kept saying he would try but eventually he stopped responding to my emails, but there was kind of a workaround.

I was able to interview TR Love from the group Ultramagnetic MCs who was able to help me piece the story of the sample together. He was friends with Paul C., one of the producers who worked on the Eric B. and Rakim album, Let the Rhythm Hit ‘Em. According to numerous accounts Paul C. was the one who found Ghetto: Misfortune’s Wealth at a flea market in the late 80s. To my knowledge, he was the first DJ who heard 24-Carat Black and decided to sample their music. He was a really influential and brilliant producer – one of the forefathers of sampling in the 80s. He died a tragic death and was murdered in 1989, so he did not live to produce the Eric B. and Rakim album, but he left behind a cassette tape with some of the records that he had been wanting to sample. Large Professor, the producer who ended up working on “In the Ghetto” heard that tape and decided to sample 24-Carat Black.

I was able to interview TR Love from the group Ultramagnetic MCs who was able to help me piece the story of the sample together. He was friends with Paul C., one of the producers who worked on the Eric B. and Rakim album, Let the Rhythm Hit ‘Em. According to numerous accounts Paul C. was the one who found Ghetto: Misfortune’s Wealth at a flea market in the late 80s. To my knowledge, he was the first DJ who heard 24-Carat Black and decided to sample their music. He was a really influential and brilliant producer – one of the forefathers of sampling in the 80s. He died a tragic death and was murdered in 1989, so he did not live to produce the Eric B. and Rakim album, but he left behind a cassette tape with some of the records that he had been wanting to sample. Large Professor, the producer who ended up working on “In the Ghetto” heard that tape and decided to sample 24-Carat Black.

N.S.: I want to pull us to the crux of your story with the closing lines of the book, by C. Niambi Steele, comparing 24-Carat Black to a dinosaur: “the dead dinosaur made the fuel that runs the world. The dinosaur wasn’t paying attention. He was too busy trying to live. He didn’t know that he was going to be fuel. And neither did I.” I think that this metaphor really sums up the dynamic between hip-hop and the soul and funk of the ‘60s and ‘70s.

Z.S.: I knew that 24-Carat Black’s story was unique and the number of rappers who have sampled this music is incredibly striking. But on the other hand, I also knew that their story fit into a larger pattern of exploitation within the music industry, and I wanted to explore the long and ugly history of predominantly black musicians being cheated out of money and recognition.

Z.S.: I knew that 24-Carat Black’s story was unique and the number of rappers who have sampled this music is incredibly striking. But on the other hand, I also knew that their story fit into a larger pattern of exploitation within the music industry, and I wanted to explore the long and ugly history of predominantly black musicians being cheated out of money and recognition.

Especially towards the end of the book, I wanted to explore some other examples of heavily sampled musicians who have been cheated out of compensation for the samples. The Amen break, from “Amen, Brother” by The Winstons, has been sampled hundreds if not thousands of times, but the drummer who played on that track never got paid for any of those samples and he died in relative poverty. That story has an unexpected ending. The songwriter behind that track was still alive and these two DJs put together a GoFundMe campaign in order to get that songwriter paid, which was kind of a happy ending. But, there’s still the fact that the drummer, who played that drum break died and never got his due. I wanted to explore just how many great musicians whose music has endured from this particular era got cheated, tossed aside like garbage once their music was no longer selling. And then, their music lives on and has a new life among DJs and rap producers, but the musicians themselves never get compensated to the degree they deserve.

The core of this issue is that copyright law, as it applies to music publishing, is really antiquated. It obviously was not written to take into account sampling. In all likelihood, if you don’t own the publishing or the recording copyright to the music, you have no recourse to get a cut of royalties when the music gets sampled. I talk about “Funky Drummer” in the book. Clyde Stubblefield, who was James Brown’s drummer, who played this legendary drum break which was sampled over 1000 times, but he never got paid. And the reason he never got paid is because he did not have the songwriting credit for “Funky Drummer.” James Brown wrote the song, but James didn’t play that break beat. Clyde Stubblefield played that break beat, and that break beat is what’s getting sampled. Logically speaking, Clyde Stubblefield was the author of that beat, but legally speaking, Clyde Stubblefield was not the author of that song. That is a longstanding problem that has created this situation where these musicians can’t get paid.

I also think that industry wide reparations are in order. In the wake of the Black Lives Matter uprisings in June, there was a good deal of discussion about racial inequities in the music industry, historically speaking. Some very prominent musicians such as Jeff Tweedy were publicly calling for reparations. I don’t know exactly what form that would take, but I do believe that they are called for. Too many musicians have been cheated by predatory contracts.

I think there needs to be some legal means of reforming the system so that musicians can maintain their copyright. Some of that needs to be baked into the record label contracts, who need to reform their own practices in order to ensure that musicians are given more ownership of their own music. This isn’t just something that affects obscure session musicians either. This is an issue that affects Taylor Swift, who is currently in the studio re-recording her earlier albums because she doesn’t own the masters. I believe there needs to be industry wide reforms to give musicians more ownership and power over their own music.

* * *

Thanks to Zach Schonfeld for taking the time to speak with me. The book is 24-Carat Black’s Ghetto: Misfortune’s Wealth. You can also find a playlist of the album and associated samples on Spotify.

———

Noah Springer is a writer and editor based in Boston. You can follow him on Twitter @noahjspringer.