Specter of Aesthetic Play

I’m deeply conflicted about how actually “good” or “bad” Ghost of Tsushima is and by what terms to evaluate it. It’s a multimillion-dollar creative endeavor backed by several million dollars in ad buys and marketing. To discuss it as an “object of art” divorced from the extensive press tour and the real-world politics at play in and around the game feels disingenuous. Simultaneously, to not allow the game’s strengths and weaknesses an opportunity to speak for themselves outside of that context also feels unfair.

So, here it goes.

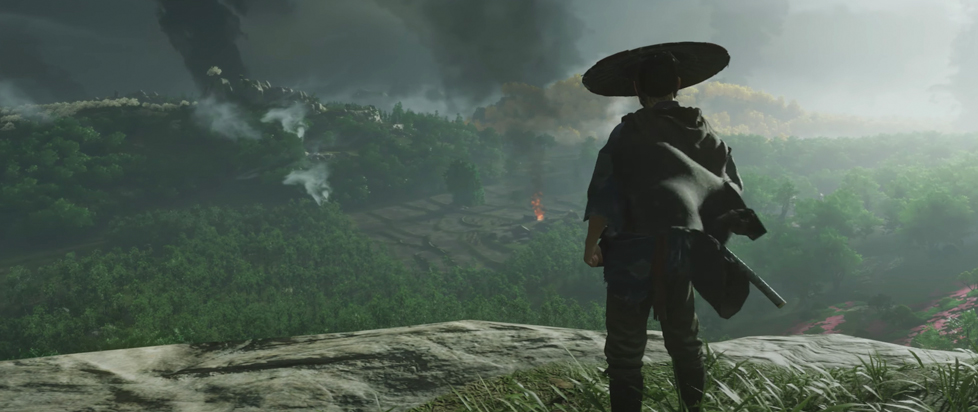

Ghost of Tsushima is a love-sick letter to the tone and feel of pop culture samurai media. It is cloyingly sentimental for a time which never existed and desperate to be loved in the same way that its creators loved the samurai cinema that they consumed in yesteryears. It is overindulgent. Despite its attempts to present a clean, focused experience it remains encumbered by centuries of media and years of the videogames that constitute its predecessors.

This baggage permeates the game to its most fundamental levels. For long durations, Ghost of Tsushima is primarily interested in what will ”look good” as opposed to what will be fun or interesting to play. The island of Tsushima presented here is a fantasy world. It’s a compilation album of what makes Japan, a nation the size of Montana spread out over 3,000 miles, a climate diverse area so picturesque and covetable to the outsider gaze. The “good” by which the game measures itself is not a feedback loop of interaction between player and game but instead a simulation of a storybook style memory. This is more than a dogmatic adherence to aesthetic over substance, it’s a dogmatic adherence to aesthetic substance.

What “looks good” grates against the utility of playing a long game. As you travel a fox will inevitably beckon you to follow. Then a bird. Then another fox. Maybe a few birds in a row. At first this is novel. These animals lead you somewhere. They bring you to interesting points that will help you in your quest. Eventually, however, you realize that for as highly touted as the lack of waypoints and horse GPS was, foxes and birds are just fox and bird shaped waypoints. I appreciate the Suckerpunch has taken the time to dress these waypoints up in the visual language of Ghost of Tsushima. What is amiss is that they reveal their “gameiness,” an uncanny sense of their functional, transactional qualities. They “look good” but they’re still only waypoints.

This “look good” first style approach also forces the camera into awkward contortions. At many points in the game its possible to trigger a standoff to instantly kill several opponents. This is a tense moment, enviously grasping at some of the great samurai standoffs like the one which ends Akira Kurosawa’s Sanjuro. However, initiating a standoff always brings up the same stale camera angles which are entirely agnostic to what is going on. Entire basecamps can stand unaware to these moments. Worse, depending on how enemies are placed, your view of each successive attacker may be blocked by a recently felled enemy.

Even more confounding is that these standoffs can be fun. It feels good to perfectly time an instant kill and chain it together with several more. Having to learn the difference between a feint and the beginnings of strike consistently brought my eyes into anime focused determination. Saving a prisoner in this manner and coldly cleaning the blood from the slain made me feel like a one-man army, fit to save my home. When it worked.

Ghost of Tsushima is at its best when it is essentially a Batman-style power fantasy. Protagonist Jin Sakai quickly evolves into a righteous vigilante willing to operate outside the law and establish his own methods, which involve a level of brutality those who stand on the side of order will not partake in. While the Mongols may have started this war and vastly escalated the rules of engagement Jin is not afraid to do this himself, to great effect.

There is an undeniable sensation of vitality when you, as a powerful warrior, stride into an enemy base, call your foes forth and then slaughtering them effortlessly. There is a near salivating kind of satisfaction sneaking into a camp and butchering those who have slaughtered so many and seek to slaughter more. For decades videogames have chased precisely this as the barometer for what makes a game “good.” Ghost of Tsushima delivers it.

But we also must remember that this is a game which claims a real-life lineage and this hyperviolence doesn’t exist without the centuries of conflict and aggression between Japan and its neighbors. Make no mistake, the Yuan Dynasty was the aggressor in this war and Japan’s defense marked the end of their eastward expansion. But this moment in history also provided a galvanizing moment for Japan. A moment around which a new militarism and nationalism grew.

We stand in the future of that moment. We stand downstream of the centuries that have flowed from it and all of the others. There is something uncomfortable about implicating a player in such a historically inspired conflict. The primary joy engine of the game, the one which drives the long sought after immersive and euphoric state, is powered by tribalism and disdain for the other. Could that engine be so successful if we were asked to even once to understand our foes beyond “enemy?” Could it thrive with any other octane than that provided by blood lust?

The conceit at the heart of this is that to start playing Ghost of Tsushima is to already give yourself over to some aspect of it. That’s a central conceit at the heart of most games. To play is to open yourself up to the narrative, controls, sounds and visuals presented. But that openness means that the narrative, controls, sounds and visual are able to enact an empathetic response. And in Ghost of Tsushima that empathetic response is bent towards the positive representation of feudal, hegemonic power.

Ghost of Tsushima exists far from the realm of a “true story.” Generously, it is a “historically informed one.” The “facts” are limited to the actual incidence of a Mongol Invasion in 1274 which began by attacking the island of Tsushima. The game is the fictional idea that there was any kind of sustained occupation or resistance. In reality, the Mongols left in about a week to continue the invasion.

Within the text of the game, however, the Mongol war effort is turned back in its final moments. Jin and his methods are vindicated. The existing power structures in Japan are shown to be weak and ineffective in light of a new enemy willing to go further than the leaders of Japan. After hours and hours with Jin directly employing his methods, it is difficult to not vindicated. You and your chosen inner circle have turned back the tide of destruction. The safety of Japan is the mantle you bear.

The game is stunningly good at achieving this feeling. From the ways it threads and nods at its cinema inspirations to the tight, engaging feel of combat. The music swells beautifully at all the correct moments. Upgrading and customizing Jin’s armor further ties you into aligning yourself with him. It’s not just enough to dress him up or down, its important to dress him for the moment.

The game itself, sealed off in a vacuum chamber and insulated from the real world that it is informed by, is often brilliant. But that feeling leads me to wonder if it should not have made more of an attempt to be its own product. It’s broad overtures at an envisioned aesthetic make me wonder what could have happened with a totally original story unfettered by its inspirations.

The game itself is not sealed in a vacuum chamber. It exists in our very real world, the one where I can see the wall beyond the edges of the TV which desperately attempts to contain the vacuum. And in that world, Ghost of Tsushima’s through line of hegemonic might against a foreign enemy portrayed as large, dark and savage is troubling. Not just because of the ways this runs counter to the actual Mongol Invasions and the actual history. It’s troubling because of how good it feels to let that wall fade and become the Ghost of Tsushima.