Towards a Carrier Bag Theory of Videogames

If a story were a shape or object, what would it be? Videogames have many answers to that question: think of the greasy Tarot cards that signify campfire yarns in Where the Water Tastes like Wine, or the flowcharts of Detroit: Beyond Human. One idea typically floats to the fore when we give shape to stories, however: a line. Perhaps a winding line, perhaps a little overgrown, but always there, singular and unambiguous. In videogames, the line may be literally underfoot, a breadcrumb trail guiding us to a waypoint. Where there is a line there is a beginning and ending. And where there is a beginning and ending, there is generally a hero.

The author Ursula K Le Guin had a few bones to pick with heroes – bones being one of many phallic bashing implements that are the hero’s stock in trade. In her 1984 essay, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction,” Le Guin challenges the treatment of the hero’s quest as some kind of primordial default, the ritual mammoth hunt from which all of civilization and culture are derived. On the one hand, she dismantles its conflation of human with Man, of technology with weapon, and of narrative action with conquest and bloodshed. But her analysis is not just about characters and deeds. It is about the hero’s quest as a phallic conception of time, “the arrow or spear, starting here and going straight there and THOK! hitting its mark (which drops dead)”. To present heroes and their deeds as an originary myth is to impose this narrow fatalism on all of history – always travelling via conflict, always ending with a kill.

Against “the linear, progressive, Time’s-(killing)-arrow mode of the Techno-Heroic,” Le Guin proposes the story as “carrier bag,” gathering its elements into “a particular, powerful relation to one another” without bullying them into order or treating them as backdrop for some Great Man’s ascent. The carrier bag story resists the annihilating clarity of the hero’s quest, forever earthing itself in either triumph or defeat: its “purpose is neither resolution nor stasis but continuing process”, made up of “beginnings without ends, of initiations, of losses, of transformations and translations.” There is still a place for conflict, but it is no longer the logic driving the story.

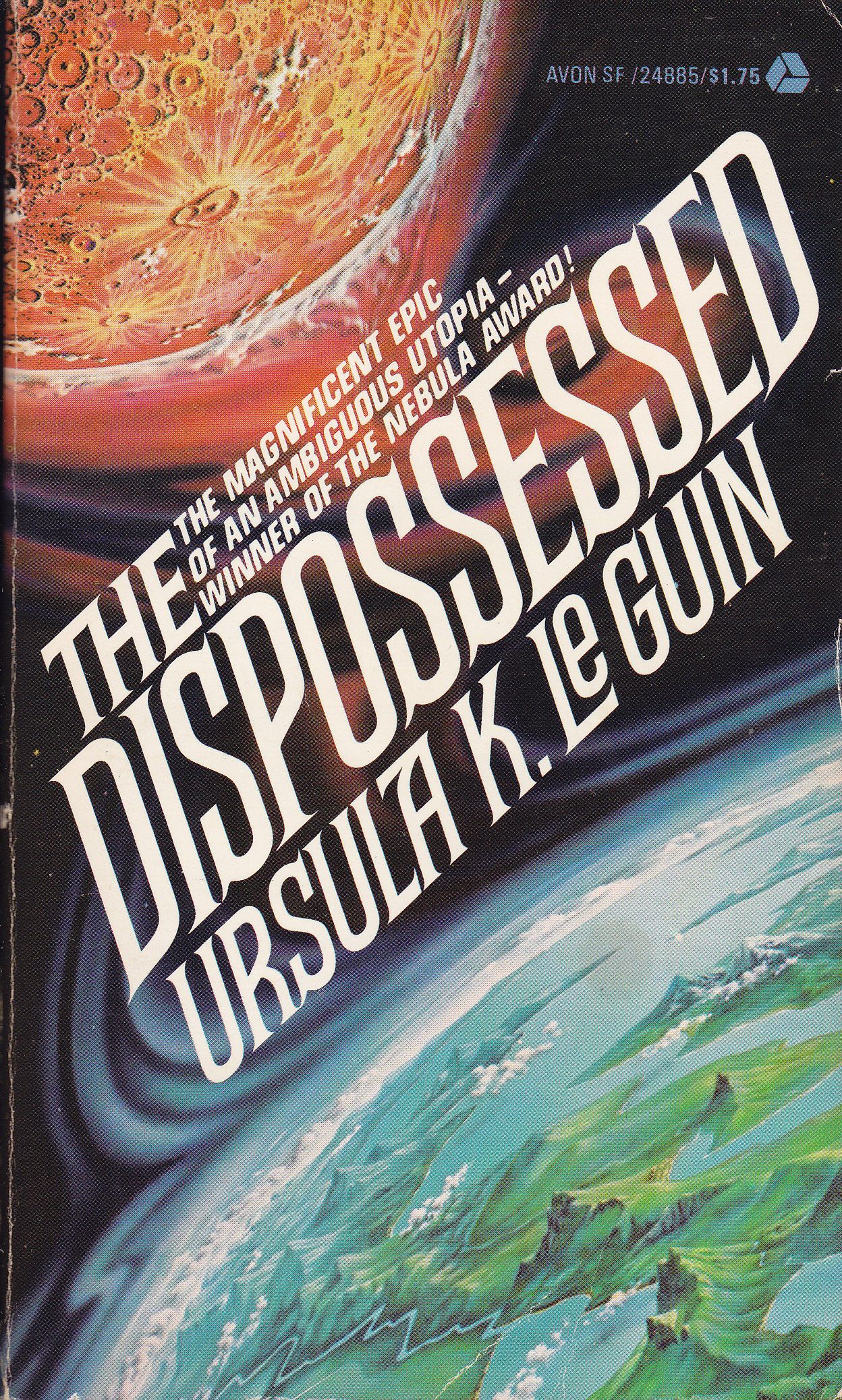

For an illustration of Le Guin’s thesis we might look to her novel The Dispossessed. It’s a tale of two worlds – Urras, an Earthlike realm of conniving nation states, and Annares, a dusky, anarchist society founded by Odo, an Urras-born revolutionary. The novel looks like a hero’s quest from afar: its protagonist, Shevek, is a genius physicist modeled on Robert Oppenheimer. Struggling to pursue his research on Annares, where innovation is associated with anti-social egotism, Shevek becomes the first of his people to set foot on Urras since the exodus. As such, he also becomes the heir to Odo’s revolution, his presence sparking an uprising, even as the rulers of Urras strive to appropriate his discoveries for military gain.

For an illustration of Le Guin’s thesis we might look to her novel The Dispossessed. It’s a tale of two worlds – Urras, an Earthlike realm of conniving nation states, and Annares, a dusky, anarchist society founded by Odo, an Urras-born revolutionary. The novel looks like a hero’s quest from afar: its protagonist, Shevek, is a genius physicist modeled on Robert Oppenheimer. Struggling to pursue his research on Annares, where innovation is associated with anti-social egotism, Shevek becomes the first of his people to set foot on Urras since the exodus. As such, he also becomes the heir to Odo’s revolution, his presence sparking an uprising, even as the rulers of Urras strive to appropriate his discoveries for military gain.

The fates of worlds hang on Shevek’s equations, but there’s more to The Dispossessed than his triumph. For one thing, his journey is simultaneously one of departure and return. The book doesn’t unfold linearly but alternates timeframes and planets, recounting Shevek’s youth alongside his experiences on Urras. Each account ends in deep space between worlds – a kind of narrative Lagrangian point – Shevek’s decision to leave Annares coinciding with his flight from Urras after the uprising is quashed. In this way the book itself performs the implications of Shevek’s magnum opus, the General Temporal Theory, which echoes Einstein in departing from the mode of absolute, linear time proposed by Newton – that heroic conception of the arrow, always flying straight.

Time, here, is diffuse and relative, “past” and “future” coterminous. The arrow accompanies itself through the air, chasing its own tail. Clear outcomes are impossible according to such a model, and as such, the book ends without picking a victor between Annares and Urras. Shevek ultimately decides to transmit his findings to the galaxy at large, refusing either planet the strategic advantage. Odo’s “revolution” proves to be endless, not the replacing of one way of life by another, but the maintenance of these kindred worlds in a fractious orbit.

Where in videogames might we look for stories like this one – rousingly unheroic, movingly irresolute? In theory we might look everywhere. Videogames have long been viewed as artworks that hold their elements in “a particular powerful relation” without locking them down. They are loose, participatory bundles of tools, props, characters and environs, distillable into an endgame but haunted by the thought of different outcomes. Videogames do not merely resemble containers: they are also defined by vessels and containers, travelling care of inventory systems – Resident Evil’s notoriously cramped item grid, Death Stranding’s teetering crates full of dead air – that may be as expressive and decisive as weapons or characters.

If videogames are carrier bags defined by carrier bags, however, we are prone to thinking of them as hero’s journeys. Discussion of even the most open-ended games is dominated by talk of “right” ways of playing and the “best” endings. Videogame narratives that deal deliberately in ambiguity, leaving scenarios in process and denying you the casting vote, tend to be branded dissatisfying, exhausting or even “unfinished,” assuming they are talked about at all.

This was certainly the response from many quarters to Ice-Pick Lodge’s diseased symbolist survival game Pathologic – and yet, Pathologic is one of the strongest examples of a game that spurns the lumbering momentum of the hero’s quest. It invites you to play the role of saviour, tasked with curing a plague before it destroys a town, only to deprive you of the customary straight line to the finish.

Among the first things you learn in the game is that you are one of three would-be heroes, representing vastly different disciplines and philosophical frameworks. Rather than vanishing when you choose a protagonist, the other two accompany you to Town-on-Gorkhan and pursue their own methods of containing the epidemic. It isn’t clear whose approach is superior, and you will probably butt heads with your colleagues as you hurry from sickbed to sickbed. You travel through the game conscious that you are but one answer to a question, and not necessarily the best. You may only be a bit part, a lesser antagonist, in somebody else’s story.

The other critical factor is that Pathologic doesn’t wait for you. You are not the narrative’s propulsive force, dragging a chain of events behind you, but a single cell churning through the body of a town that changes, day to day, without your permission or awareness. Understanding that body as it sprouts, bleeds and decays requires curiosity, patience and a sensitivity to the resonances between people and possibilities, rather than the mere drive to overcome. You must become not a conqueror but a “weaver,” in the words of narrative designer Alexandra Golubeva, tracing buried lines and helping to bind the whole together as it lurches towards the sunset. “In a way, the protagonist collects what was scattered.”

The act of collecting what is scattered defines how last year’s remake, Pathologic 2, visualizes its story. There’s no list of main and secondary quests, no meteoric arc to the finish with token offshoots for completionists. Each day in the game offers up a “mind map” of goals and hints, strewn across the screen like a pocketful of scrying stones. Golubeva argues that the interchangeability of these nodes, together with the unpredictable way they are added to the mind map, stops players from “sticking to any single pattern of interaction.” Some approaches are more hazardous than others, but there is no wrong way of playing.

Composed at the height of the Cold War, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction” has only grown more relevant as dread of nuclear annihilation has given ground to climate change anxiety. It has proven a fruitful resource for later ecotheorists such as Donna Haraway, who treats Le Guin’s mourning for the humans that hero quests ignore as an opportunity to move beyond “the human” entirely. The less encouraging reason for the essay’s endurance is that we are still in thrall to heroes and their journeys, seeking consolation in the tragic fortunes of outsized individuals. “We’ve all let ourselves become part of the killer story,” Le Guin writes. “And so we may get finished along with it.” It falls to storytellers and their audience, the makers and players of videogames among them, to set aside time for other shapes of story.