Spectating at the End of the Universe

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #123. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #123. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Finding deeper meaning beneath the virtual surface

———

In Ways of Seeing, art critic John Berger establishes the impact perspective has had on the medium of painting. Perspective “centres everything on the eye of the beholder . . . Everything converges on to the eye as to the vanishing point of infinity. The visible world is arranged for the spectator as the universe was once thought to be arranged for God.” Such a powerful tool allowed artists to contextualize their paintings, to add depth to their worlds and to situate the viewer within these worlds for the first time.

There are shortcomings to traditional perspective, however. Perspective, in reality, is not infinite; we are not gods, nor are we the center of the universe. Time passes, images change, new perspectives reveal new truths. To pretend that the view you currently have is the only correct one, simply because it is the view you have always had is to embrace stagnation and even death.

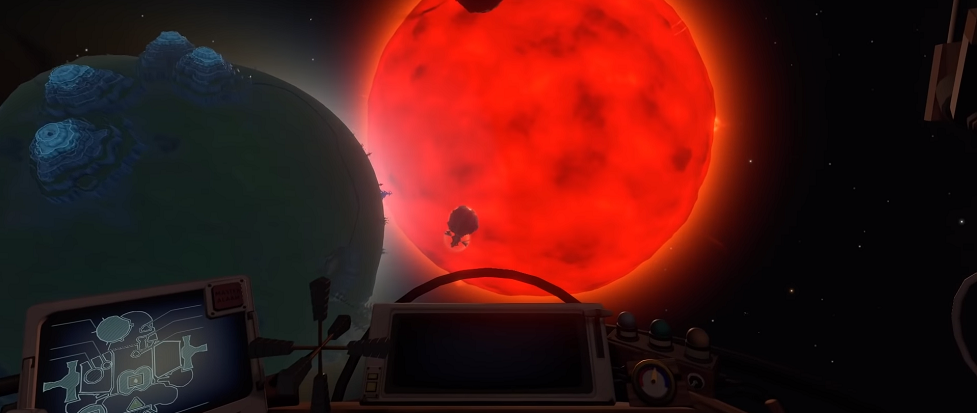

Mobius Digital’s Outer Wilds is a game that, at its black hole of a core, is a rebellion against this easy acceptance of an ordered and subject-oriented universe. In it you play an astronaut, from a race of aliens firmly committed to recklessly ambitious space exploration, piloting a rust bucket of a ship away from your tiny home planet and throughout as much of the solar system as you are able to explore in the 22 minutes you get before the system’s sun happens to explode. Then you wake up and do it again (and again).

The view from your home planet is a traditional one: space and stars, a bright sun that casts long shadows (albeit over a dramatically shorter day/night cycle), grassy hills in the near view and stony mountains in the distance. Your village is at the center, and around it everything seems to revolve. But once you lift off in your ship, the planet shrinks to a pebble, other planets and moons loom larger and smaller as you zoom past, their states ever-changing as the sun counts down to supernova. Some planets crumble over time, others fill up with ash. Fly across the ocean surface of the water planet, Giant’s Deep, and you might find that an island you had previously visited has disappeared, launched into the stratosphere by a massive cyclone.

These dream-like landscapes, shaped by time, mysterious gravitational anomalies, and the existential punctuation of a dying sun, reflect a famous art movement that challenged traditional modes of perspective: Surrealist art, which is described by the poet Arthur Rimbaud, as “a long, immense, and rational dissoluteness of all the senses . . .” by which “The Poet makes himself a seer” and “. . . arrives at the unknown.” To quote Jodie Foster in Contact, “they should have sent a poet” and in Outer Wilds, they do. Or rather, they send someone open to significantly changing their perspective, open to diving into dreamlike and dissonant experiences, into the unknown and the unknowable.

The Surrealists, whose movement reached its height in the brief period of peace between the twentieth century’s two world wars defined themselves in opposition to the cold logic and calculation of war and the capitalistic societies which supported it. Outer Wilds, in turn, rejects the cold aesthetic trappings of normative imperialist sci-fi fantasy. Instead of grey metal and space marines, it textures itself with uneven wooden planks and rustic camping paraphernalia. Your space suit isn’t some Syd Mead-inspired, form-fitting piece of tactical armor. It’s a baggy diving bell held together with tape and glue. The citizens of Timber Hearth are not driven by any manifest destiny beyond an unreasonable fixation on flinging themselves into space and trying to find something weird or cool to bring back (or just staying out there and chilling at a campfire until the end of time).

It’s also an exercise in impermanence. Because you are stuck in a time loop, everything around you is forcibly ephemeral. And since each planet winds out a unique series of events over time, visiting a place early in the session usually offers a radically different experience than dropping in a few minutes before the sun pops. The buried pedestal becomes a towering monolith, the pathway crumbles, the wandering comet’s icy surface melts and reforms as it completes its orbit around the sun. You dash about trying to decipher unearthed tomes in the few remaining moments before that final shockwave erases all evidence of your existence. This time-based fluidity promises success according to the Surrealist formula that only in the chance and unexpected encounter can beauty be found.

And there’s beauty everywhere, each planet you visit writes its own poetry out of extreme contrasts. Even the beauty is contrasted with the ever-present danger you must overcome in order to experience it: the cold vacuum surrounding you, the deadly falls, the life-sapping dark matter and finally the cataclysmic sun itself. Against this danger, the beautiful stands out even more starkly, its luster brightened by the dark vastness that surrounds it.

Since you are always aware of your imminent demise, the pressure to observe, to draw in new experiences before your time runs out, is intensified. Each new day you wake up by the sleepy campfire down on Timber Hearth only serves to make you feel more distant from it. All your hapless brethren, continuing their own lives unaware of what’s about to come down on them, feel less and less relevant to the game and to your journey. They’re happy in their ignorance, never having seen, as you have, the other side of the veil.

The Surrealists, familiar as they were with war and destruction, reacted, rebelled against this gormless satisfaction with history and institutions. One artist, Desmond Morris wrote: “I was rebelling against mass violence and hatred, so my rebellion had to be some other, more positive kind . . . My artistic rebellion took the form of turning my back on accepted, traditional art and associating myself instead with the Surrealists.” The world of the Surrealists did not feel stable or infinite, they had seen the great powers of the world commit to the suicidal impulse of world war, and after such a cataclysmic sight, who would be foolish enough to believe in an idyllic future? It’s no surprise then that they threw off the normal to embrace the weird, to dive into dreams and drum up the mysterious. To search frantically for an uneasy beauty.

It’s no surprise either that, by behaving similarly, Outer Wilds resonates so well with us in our own uncertainty-filled present day. What use is the safe, the traditional when nothing around us feels remotely secure or stable? Why not then, interact with art that shows us the strange and random, the frightening and beautiful? Why not challenge our own centered perspectives with a miniature universe full of cosmic wonders and horrors, a glimpse at what one kind of ending might look like, so that we might become better able to reckon with our own?

———

Yussef Cole is a writer and visual artist from the Bronx, NY. His specialty is graphic design for television but he also enjoys thinking and writing about games.