Best Games Architecture of 2019

I’m not really a big fan of lists because I find them to be overly reductive. The only thing worse than a list in my book is a grade or some sort of score. This might sound strange coming from somebody who clearly just made one, but architecture featured prominently in games this year, so I decided to swallow my pride and put together a list of the top ten examples. In order to pretend that I’m still holding onto my principles, though, I decided to make it an unranked, strictly alphabetical list. Without further ado, these are what I consider to be the top ten games of 2019 from an architectural perspective.

A Plague Tale: Innocence

You’ll find plenty of Gothic architecture in A Plague Tale: Innocence, but you’ll come across a couple of other interesting things, too. There’s a bit more in the game than just flying buttresses and soaring spires. A Plague Tale: Innocence features quite a few structures in the Romanesque style and even some examples of the Roman architecture that inspired it. The game is pretty impressive in terms of the different types of building that it features, too. A Plague Tale: Innocence has everything from tiny towns to huge cities. Castles. Churches. Universities. I’m an archaeologist by profession, so I was of course captivated by the ancient aqueduct. Something else about A Plague Tale: Innocence that definitely merits more than just a passing mention is the interior design. I have a soft spot for Medieval furniture, so this aspect of the game was a real treat for me.

Control

Brutalism is best known for being blocky, so it’s hardly surprising to find this architectural style in a lot of games, but it finds a truly fascinating expression in Control. The game interprets Brutalism as opposed to simply featuring it. I don’t know about you, but I’ve always found there to be something slightly unsettling about this particular style of architecture. With its geometrical forms and patterns, Brutalism has always looked so artificial to me that it seems almost supernatural. Control picks up on this aspect of Brutalism and really runs with it. Approach a control point for example and you’ll see a bunch of blocks and slabs which have been awkwardly arranged around a black pyramid. When you cleanse the control point, these rearrange themselves into a much more familiar form. The strange mass of materials becomes a building.

Devil May Cry 5

Metabolism was quite influential for a couple of decades, but it barely spread outside of Japan. Searching for a solution to the endless process of urban renewal in Japanese cities after the Second World War, the architects behind Metabolism, Kisho Kurokawa and Kiyonori Kikutake, started to think about the problem in terms of biological growth. The idea was to make buildings using prefabricated units that could be added or subtracted over time. (I wrote about this in Issue 118 of Unwinnable Monthly, so check out that article for more information). You can see a hint of this influence in Devil May Cry 5. Stroll through the game world and you’ll see it slowly coming alive. Buildings become bones. Train tunnels turn into tracheae. Metabolism barely spread outside of Japan, but the game shows that it definitely spread outside the field of architecture.

Fire Emblem: Three Houses

You often come across cathedrals in games, but you rarely get to see the dormitories, refectories or libraries that are almost always attached to them. The fact is that cathedrals aren’t just buildings. They’re institutions. Cathedrals are typically associated with a whole series of structures that provide for the needs of a particular community. These tend to be convents, but schools and hospitals are pretty common, too. I can’t think of many games that communicate this quite like Fire Emblem: Three Houses. While it definitely has a cathedral, the monastary where the game takes place, Garreg Mach, is filled with all sorts of different structures. You can talk to students in the dormitory, cook up a storm in the refectory and hit the books in the library. This leaves you feeling as though Garreg Mach is more than just a bunch of buildings. You get the impression that it’s an actual institution.

Judgment

Stroll through the streets of a Japanese city and you’ll come across a lot of strange buildings. These are sometimes products of a particularly innovative architect, but most of the time they’re nothing more than material manifestations of the various rules and regulations about construction in Japan. The most important of these are known as the jiguchisen, nichiei, densen and taishin. (I wrote about these in Issue 119 of Unwinnable Monthly, so I won’t get into any of them, but you can read through that article for the details). These were largely responsible for determining the size and shape of almost every single structure in the country. The game is notable for more than just respecting the relevant construction codes, but Judgement provides a reminder that extraordinary architecture is often the result of what are actually mundane forces.

Manifold Garden

I can’t think of too many games which call into question the definition of architecture. Manifold Garden is actually the only one that comes to mind. The game world is a manifold, so it’s a topological space which is connected, but remains Euclidean around each point. This means that distinctions between things like inside and outside are basically meaningless because you’re both inside and outside of every single structure in the game world at any given point in time. (I won’t go into detail about this, but I discussed it at length in Issue 122 of Unwinnable Monthly, so you can take a look at that article for more information). This definitely breaks your mind, but it forces you to reconsider your assumptions about what architecture is meant to accomplish, too. In theoretical terms, architecture is about creating order by manipulating form and space. Because it manipulates form and space almost past the point of creating order, Manifold Garden poses a real challenge to this idea.

Metro: Exodus

Architects make a whole bunch of assumptions about how a building is going to be used. When they start using a structure, the first thing which people do is to make it their own, though. Walls are sometimes knocked out. Rooms are often repurposed. The fact is that architects are almost never able to predict how people actually use the buildings which they design. People do surprising stuff. This kind of surprising stuff is known as adaptive reuse. You can see signs of adaptive reuse in lots of different games, but Metro Exodus contains quite a few notable examples. The best one is probably the lighthouse which you’ll come across on the dusty shores of the Caspian Sea. While it was presumably meant to warn passing ships about some sort of danger, the building has apparently been turned into a cozy apartment by a scavenger called Giul. Most other parts of the game world are filled with similar structures.

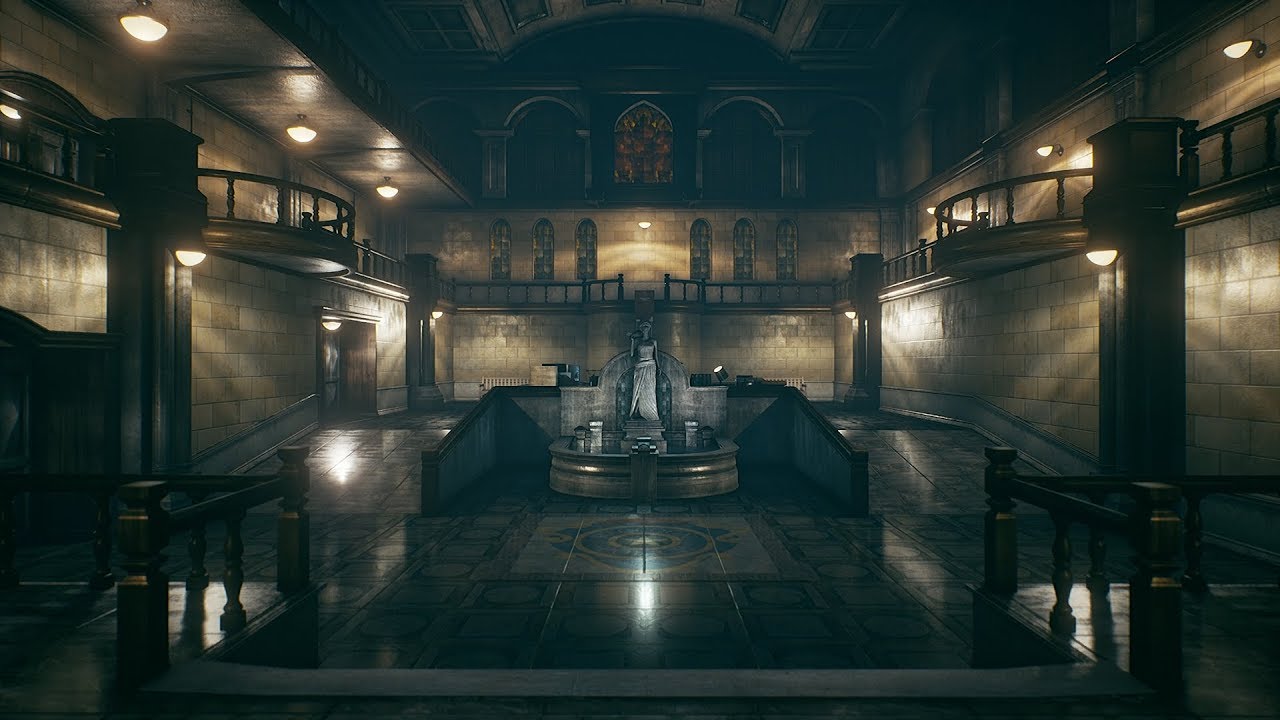

Resident Evil 2 Remake

The game world in Resident Evil 2 is pretty big, but if you decide to play the game, you’ll spend most of your time in the part known as the Raccoon City Police Station. While the building is definitely beautiful, it’s notable for something else, too. The structure communicates a particularly strong sense of power and authority. You can see this in several different features of the building like its focus on symmetry and use of stone. Step into the Main Hall and you’ll see exactly what I mean. With its axial arrangement and frigid materials, you don’t have to know a lot about architecture to figure out that it’s meant to make you feel small. This part of the structure consists of an open courtyard with columns on either side and down the center. Parallel sets of stairs overlooking a double door give access to a second story. The floor is marble. The walls are made from the same material. What you’re seeing on display is the absolute power and authority of the police.

Sekiro

I have a passion for Japanese architecture, so exploring the game world in Sekiro was pretty much nothing but pure pleasure for me. In terms of traditional architecture, it has basically everything that you could possibly want. Palaces in the shoin style. Castles in the sukiya style. Buddhist temples. Shinto shrines. You’ll come across all of this and quite a bit more in Sekiro. The attention for detail is impeccable, too. The roof tiles known as shibi, and used for tiling steps in Japan as well as roofs, for example, are featured prominently in the game. These take the form of a smiling shachihoko in some places, but they appear as a scowling onigawara in others. (The former is a fish and the latter is a demon). The best part is that you’re able to climb all over the buildings in most parts of the game world, so you can take a long look at these fascinating details up close.

The Outer Worlds

Since it features what are basically identical structures, The Outer Worlds might seem like a strange entry on this list, but it’s precisely this aspect of the game which makes it so interesting from an architectural perspective. The buildings which you’ll come across in The Outer Worlds aren’t beautiful. They’re actually rather bland. This was definitely done on purpose, though. The structures are supposedly prefabricated units meant for temporary habitation by the colonists of a star system known as Halcyon. They were only intended for use while things got up and running, so these buildings were presumably going to be replaced at some point, but nobody ever seems to have pulled them down. Why is this interesting? The structures in The Outer Worlds provide a reminder that quick fixes often become permanent solutions when it comes to architecture.