Anomalous Architecture

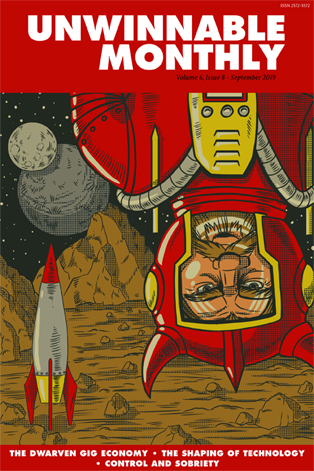

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #119. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #119. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Architecture and games…

———

Take some time to explore Kamurocho and Sotenbori in Yakuza Kiwami 2 and you’ll see some strange buildings. You’ll find plenty of small structures, but you’ll come across a couple of curiously shaped ones, too. What’s the deal with all of this anomalous architecture? The answer is mostly a matter of laws and bylaws.

The developer behind Yakuza Kiwami 2, Sega, wanted Kamurocho and Sotenbori to look like real cities. They weren’t supposed to be in Europe or America, though. They were supposed to be in Japan. When it came to creating the buildings in Yakuza Kiwami 2, Sega, in other words, had to carefully consider Japanese practices of construction. This meant brushing up on the relevant rules and regulations.

While most of them are the same as what you’ll find in Europe and America, some of the laws and bylaws in Japan are a bit strange. Taxes for example used to be assessed based on frontage, so properties tended to be long and narrow. They became small and square when taxes started being assessed based on surface area. This was about the time when people began to build upwards rather than outwards, too. The system of taxation has created a couple of quirks, but the construction codes have also produced plenty of peculiarities. There’s a code about the maximum amount of sunlight that a building can block. There’s another one about the minimum distance that a structure can stand separated from overhead power lines. There’s even a code that basically bans party walls. These laws and bylaws have all made their mark on Japanese architecture.

Japanese architecture has been shaped by these regulations to such a point that many of the buildings that you’ll come across in cities like Tokyo and Osaka are basically nothing more than material manifestations of the various rules that have been put in place over the years. The same could be said about the buildings in Kamurocho and Sotenbori.

Spend enough time playing Yakuza Kiwami 2 and you’ll pick up on something strange: most of the buildings in Kamurocho and Sotenbori are particularly small. They’re only small when it comes to surface area, though. Pretty much all of them have a second story. The reason for this can be traced back to a tax called the jiguchisen that was assessed based on frontage. This tax resulted in the spread of unagi no nedoko. The literal translation for this term is “eel’s nest.” Most of the townhouses known as machiya that stood on these long and narrow properties were destroyed in the Second World War, but they began disappearing quite a bit earlier when the jiguchisen was replaced with a tax that was assessed based on surface area. Trying to avoid a hefty tax hike, people in Japanese cities like Tokyo and Osaka subdivided their properties into small squares. These were in many cases never reassembled. You can see an example of this in the part of Kamurocho called Champion.

Some of the buildings that you’ll come across in Kamurocho and Sotenbori are curiously shaped. You’ll find quite a few buildings with curved corners, but many have angular exteriors, too. Similar to why Japanese cities like Tokyo and Osaka are filled with small structures, the reason for this anomalous architecture can be traced back to the various regulations. In this particular case, it happens to be a result of the construction codes known as nichiei. These construction codes restrict the amount of sunlight that a building can block, so tall towers often look like they’ve had random pieces and portions removed from their intended design. Featuring curved corners, the biggest building in Kamurocho, Millennium Tower, is a good example of this. With its angular exterior, the Omi Alliance Headquarters provides a pretty good example, too.

Japanese cities like Tokyo and Osaka are famous for their overhead power lines. These can be found crisscrossing streets and stretching over structures in every part of Japan. Their appearance definitely grabs your attention, but that’s hardly why they’re there. These overhead power lines literally keep the lights on. They’re pretty important and this means they’re protected by all kinds of rules that are supposed to keep them safe. There’s one in particular called the densen, which establishes the minimum distance that a structure can stand separated from overhead power lines. The densen is definitely sensible when it comes to health and safety, but it’s responsible for some pretty odd architecture. Signage, for example, can’t always stretch into the street. Buildings can sometimes only have a certain number of stories, too. Kamurocho and Sotenbori are filled with examples of both.

Walk around Kamurocho and Sotenbori for long enough and you’ll notice that most of their buildings are separated from each other by a narrow gap. There’s a good reason for this. Japanese cities like Tokyo and Osaka have always been prone to earthquakes, so quite a few regulations have been put in place over the years to keep them from falling over when the ground starts to shake. Taking the form of construction codes called the taishin, these resulted in the almost complete disappearance of party walls. Since buildings that have them are less structurally sound than buildings that don’t, most of the party walls in Japan were sacrificed in the name of health and safety. You can see how this works in Kamurocho and Sotenbori. They’re often filled with trash, but you’ll come across a narrow gap in between almost every building. You’ll find some pretty good examples of this in the part of Sotenbori called Syofukucho.

You’ll come across quite a few strange buildings in Kamurocho and Sotenbori. The reason for this anomalous architecture can be traced back to the various rules and regulations that have been put in place over the years. The most important of these are known as the jiguchisen, nichiei, densen and taishin. Japanese architecture has been shaped by these laws and bylaws to such a point that most of the buildings that you’ll come across in cities like Tokyo and Osaka are basically material manifestations of them. Shouldn’t every building be exactly the same, then? The answer is that nothing nourishes creativity quite like constraint.

The laws and bylaws known as the jiguchisen, nichiei, densen, and taishin are basically just a bunch of constraints. Similar to most constraints, they forced architects to think outside of the box in terms of what could actually be created. In other words, the rules and regulations in Japan stimulated rather than stifled creativity. While this definitely explains why every building in Japan isn’t exactly the same, it also helps to explain why Kamurocho and Sotenbori are such interesting places. When it came to creating the buildings in Yakuza Kiwami 2, Sega had to think a bit outside of the box, too.

———

Justin Reeve is an archaeologist specializing in architecture, urbanism and spatial theory, but he can frequently be found writing about videogames, too. You can follow him on Twitter @JustinAndyReeve.