You Were Never Really Here

This is a reprint of a mini-essay from Issue #12 of Exploits, our collaborative cultural diary in magazine form. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for $2 or subscribe to never miss an issue (note: Exploits is free for subscribers of Unwinnable Monthly).

This is a reprint of a mini-essay from Issue #12 of Exploits, our collaborative cultural diary in magazine form. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for $2 or subscribe to never miss an issue (note: Exploits is free for subscribers of Unwinnable Monthly).

———

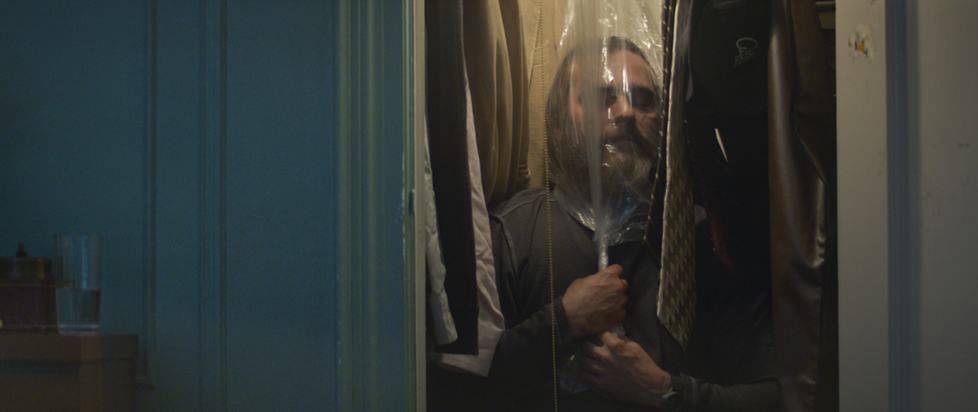

You Were Never Really Here opens with Joe’s head in a plastic bag. Through the bag, we hear the sounds he hears: a cacophony of the various traumas of his life, overlapping. We also hear Joe counting down to silence these noises. It’s the same technique he used as a child. It works (if you could call it that) the same way it did then: all the sounds blend, quiet and become indistinct. He’ll always hear them, but the bag muffles them.

Even after the bag comes off, however, sounds come to Joe – and us – much the way they did inside it. The city is cacophonous. In every scene, a deluge of aural information overwhelms Joe, and us. These sounds overlap with one other, with the movie’s score and with the actual dialogue, until they all become equally indistinct. Joe doesn’t get to pick and choose which realities he muffles.

You Were Never Really Here doesn’t just “show, not tell” us that Joe’s trauma has forced him to dissociate from the world. Instead, its sound design has us feel Joe’s dissociation with him. That same design explains how Nina, the girl Joe saves from sexual slavery, comes to experience the world the same way he does. When Joe finds her, we hear her counting down, too, even though her lips aren’t moving. It also helps us feel how Joe’s mother was the one person he could still connect with. Joe responded to the sounds his mother makes. They could argue, joke and sing together. The only silent scene in the movie is when Joe finds her body.

Joe fills his mother’s body bag with rocks, takes her to a river and prepares to sink with her. As he drowns, we hear him counting down. Joe has a change of heart when, mid-count, his voice changes into Nina’s. Instead of dying with one person he can connect to, he decides to live with a new one. Joe tracks Nina down to save her from her captor, only to find she doesn’t need to be saved. Instead, she saves him. The movie ends with Joe having a vision of his own suicide. He shoots himself in the head in a diner. None of the patrons react – except Nina. She returns to the table, softly touches Joe’s head (around where the bullet would have exited), and smiles at him. Maybe she heard it, too.