The Ethics of a Human Whopper

By the late 90’s the concept of vegetarianism had even penetrated as large and scarcely populated a state Wyoming, and most folks I ate with were pretty accommodating when I cut meat out of my meals. And as luck would have it, rumor was the local Burger King carried a veggie Whopper and I already had great nostalgia for mayo and a flash-defrosted patty mere months into my meatless tenure I cruised on over. But after timidly conveying my order, the cashier said with a Machiavellian glee “oh yeah, we got those” and I felt the need to hustle on out in case I was handed something on a sesame seed bun that was decidedly not vegetarian.

So went my first lesson in food self-reliance. The problem was a lack of discipline—when one severely limits their diet, they can no longer take the established food infrastructure for granted. Being a shithead teenage boy, I never really thought about cooking, or the origin and composition of my food. I could put it away by the pound for sure, but source and preparation was rarely my concern. It was only after meeting a number of alarmingly cute people who were actively considering the production of what they noshed that I felt compelled to do the same.

Thinking about what you eat isn’t typically the purview of videogames, though food very much is, as demonstrated by writers such as Nicole Carpenter. She has a resonant piece on the way we frame our lives around food, discussing recent games like The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild and Battle Chef Brigade that crack videogame dishes into something more than a mere health restorative. Her final paragraph seals the bag: “When food comes alive, it transcends the idea of being a harbinger of health. The definition of what food can do in games is changing. Food isn’t only for eating anymore.”

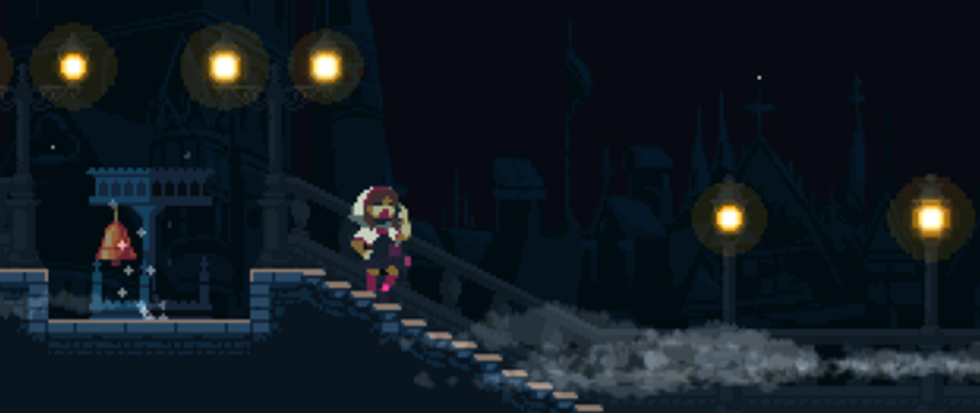

These ideas, of food in games as something more than a vessel of health or the act of consumption, settles like a river mist over Vampyr. In this recent third person semi-open world action narrative, you’re a fresh-faced vampire in a war ravaged England trying to navigate what you’ve become and reconcile it with your previous humanity. There’s skill trees, infuriating enemies, and lots of interacting with non-player characters. But its most distinguishing feature is that array of districts, each filled with citizens of London you get to know, help, and potentially eat.

As Dr. Johnathan Reid, you stalk the slick cobblestone alleyways looking for your maker, existing in constant temptation. As you heal the sick, they become juicier targets for your fangs—offering up loads more experience than fighting random vampire hunters or crusty skals. But each citizen is connected to a web of others, and eating one snips the thin threads between them and all the rest, changing how the story unfolds and weakening the districts that you are barely keeping sutured together.

So you must consider your food, and consider it carefully. It may be possible, with great patience, to go through the game on a Twilight-esque “vegetarian” diet of foot soldiers and rats. There are other temptations though: a few the locals you claw back from the clutches of fatigue and influenza aren’t exactly saints, and a case can be made that the world would be fine without them and you’d be better off full of their juicy blood. But as you unlock hints to make these human fillets more tender, you learn more about their lives and how even the lowliest scum is wrapped in billowing shades of possible redemption. Each one of them is a living being, but they are also your sustenance. We are told from the very beginning that Reid’s thirst for blood can become a powerful motivator, like a starving dog. Before he knows what he’s doing he has bitten and drained his sister of her life, she asks why as he howls in confusion and self-pity, at once choking on regret but his body more alive than he’d ever felt before.

This leaves me thinking of the rancher kids I went to school with. They would raise a calf from birth only to sell it at market, knowing that its destiny led to the dinner table. Their farm dogs were named loyal companions, but the chickens either laid eggs or had their heads twisted off to become dinner. Swine and octopi are some of the smartest animals on the planet, but they can’t directly communicate with us; yet Dr. Reid’s best marinade is to directly interact with and improve the lives of the people he’s grooming to eat.

As Reid swells with immense strength, Vampyr demands that you reckon his food, foster their health and good will, before mesmerizing them towards a secluded corner to sup on their newly restored vigor. We are forced into a mealtime mindfulness that most of us barely apply to our daily lives—is this city merely Reid’s grocery store, or do you wear a veil of humanity by grasping your last scraps of compassion for sentient life less powerful than you? When the majority of our country consumes the flesh of an animal nearly every day, who are we to judge a being who has surpassed us on the food chain? I don’t know that Vampyr adequately answers these questions, but it forces a dilemma for the player as the enemies get flamethrowers and dark powers of their own at a seemingly exponential rate. This game adds salt and pepper to the typically strict binary of “good” and “evil” actions a player can take, by shifting those choices onto a dinner menu. We are tasked to empathize with the monsters that may hunt us, while holding a mirror to our parallel habits when it comes to the things we eat.