AlphaGo

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #101. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #101. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Every week, Megan Condis and a group of friends get together for Documentary Sunday, a chance to dive into the weird, the wacky, the hilarious and the heartbreaking corners of our culture. This column chronicles all of the must-watch documentary films available for streaming.

———

Games have always been one of the primary tests that we use to measure the abilities of artificial intelligences. As self-contained systems with measurable outcomes and scoring systems that allow scientists to track incremental improvements, games are a perfect petri dish in which to observe machine learning. Computers have bested human opponents at a variety of games including Chess, Poker, videogames like Breakout and DOTA 2, even quiz shows like Jeopardy! but, for a long time, the ancient Chinese board game Go was considered to be the one game that no computer would ever be able to crack.

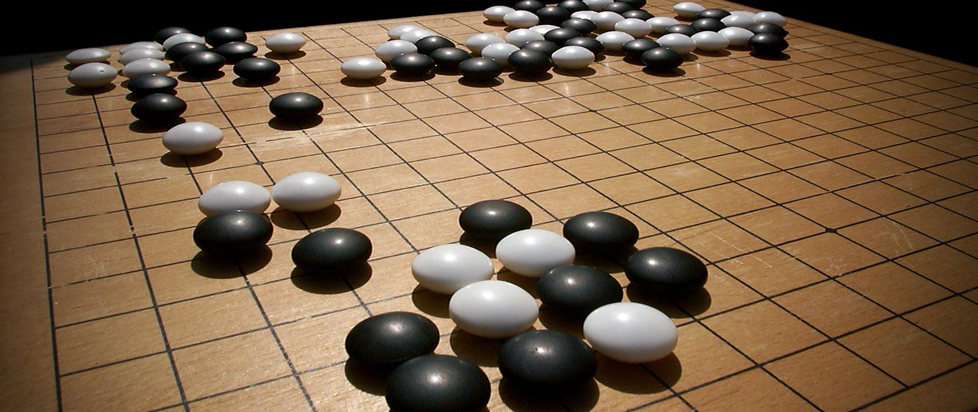

Go is the most complex game ever invented by man. Though its rules are simple (capture territory by surrounding it with your own stones while avoiding being trapped by those belonging to your opponent), the sheer number of available moves (there are more possible configurations of a Go board than there are atoms in the universe) make it an exceedingly difficult game to master. This means that it is impossible for even the fastest supercomputer, let alone a human being, to contemplate all of the available moves and their various consequences at once. As a result, an almost spiritual aura surrounds the game. Top players think of it as more than just an idle pastime. It is a philosophy, a method of intellectual refinement and soulful refinement, a metaphor for geopolitical systems and an expressive art form. Excellent moves are described not just as clever or efficient but as beautiful or even divine. Learning how to play Go means learning to understand oneself as well as one’s opponent. It is a venue through which players can showcase their humanity. Therefore, it is the perfect test for an inhuman, intelligent program, a Turing Test that doesn’t rely on language.

AlphaGo (Kohs, 2017) follows the programmers at DeepMind as they test their creation against the top Go player in the world, legendary 18-time international champion Lee Se-Dol. While the first half of the film strongly resembles many a David vs. Goliath narrative, with the programmers frantically coding to prepare for a match that commentators the world over were certain would be an embarrassing failure for their machine, the second half of the film asks us to reconsider just who it is that we should be rooting for. Would a DeepMind win represent a victory for mankind or a failure? Are we prepared to live in a world where the inhuman has evolved to become more human than we are? Who is really the underdog in this contest? Which side should we be rooting for?

As the five game long match progresses, interviews with Lee and the DeepMind team invite us to envision what artificial intelligence might have to teach us about humanistic concerns. If, as the professional players posit, Go requires one to understand their opponent’s motives and to make predictions about what it is they value and how they will pursue their goals, then a masterful AI might seem threatening. A computer that gets too good at Go might be a computer that is able to manipulate our institutions to its own advantage in unforeseeable ways. It might even decide that it doesn’t need us around anymore.

However, even as AlphaGo stokes our fear of a potential robot apocalypse, it also suggests that they may be misguided. Our tendency to anthropomorphize our own creations means that we tend to assume that artificial intelligences will be driven by the same base desires that we are. But what if the way that the robots play Go teaches us a new way to be human? If artificial intelligences can figure out unforeseen ways to look a board that represents life in all of its complexity, then is it possible that their play could teach us a different way to live, a different way to define happiness, a way to organize our world to maintain peace and seek prosperity? As our machines become more and more clever, our fate may very well lie in the way that we react when they surpass us. Will we lash out and try to punish them for their hubris? Or will we sit back and listen to what they have to tell us about ourselves?

———

Megan Condis is an Assistant Professor of English at Stephen F. Austin State University. Her book project, Gaming Masculinity: Trolls, Fake Geeks, and the Gendered Battle for Online Culture, is under contract with the University of Iowa Press.