Violent Videogames are Violent

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #101. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #101. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Revisiting stories, old and new

———

It can be difficult sometimes to know on which hill one is willing to die.

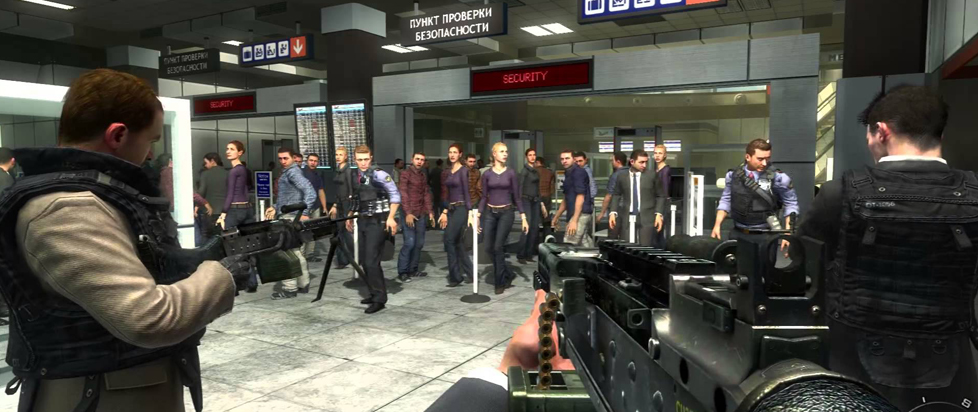

After the February 14 mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, in which 17 people were killed and 17 wounded by a 19-year-old former student of the high school armed with a semi-automatic rifle, the President of the United States met with videogame industry executives and the president of the Entertainment Software Association to discuss violent content in videogames. Reportedly, the meeting began with a video composed of clips of violent content from a variety of games. This video was posted later in the day to the White House’s official YouTube account.

It is not clear whether this meeting will result in any policy. It is not clear whether any specific policy is even under discussion. In another administration, this might be remarkable. (In 2013, Vice-President Joe Biden convened a not-entirely-dissimilar meeting with videogame industry representatives after the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary in Connecticut in which 26 students and staff members were killed by a 20-year-old man with a semi-automatic rifle. No policy changes resulted from this meeting, and it was quickly clear that no policy changes were under discussion within the administration).

If the goal is to prevent gun violence, the science, as reported by Simon Parkin in The New Yorker, is pretty clear in the conclusion that regulating violent content in videogames would be almost entirely ineffective. While the Sandy Hook Elementary shooter apparently played a lot of videogames, his clear favorite was reportedly Dance Dance Revolution.

It has been easily twenty years since I have fired a gun, but as a Boy Scout, instruction in responsible firearm use and target shooting was part of my adolescence. I have on various occasions shot a .22 caliber rifle, 12- and 20-gauge shotguns at still and moving targets, and a black powder muzzle-loaded musket. I enjoyed all of these experiences, even if I never came close to hitting an airborne clay pigeon.

At the same time, I am deeply skeptical of arguments that gun ownership in the United States should be as lightly regulated as possible. In particular, I am not convinced that semi-automatic weapons are necessary for hunting or recreation, or more accurately, that legitimate interests in hunting and recreation using semi-automatic weapons outweigh the outsized impact these weapons have when used to harm people, especially in groups. I am entirely in favor of severe restrictions on magazine capacity, and would be just as happy were removable magazines to be banned entirely.

And all of this is neither entirely here nor there. I am neither a lobbyist nor in any meaningful sense an activist, and no significant policy restrictions on either violent content in videogames or firearms of just about any kind appear to be under serious consideration. The teenage survivors of Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School demand action forcefully and eloquently, but they do not appear likely to get it. The chances of my voice adding significantly to either the largely frivolous debate over violence in videogames or the quite literally life-and-death impasse over gun violence and firearm regulation are just about zero. There is no hill to die on. There are only people dying.

The problem with high-capacity semi-automatic firearms is not that they allow a person to hurt another person. We are in such matters, as history shows, creatures of an unfortunate genius when sufficiently taken by the desire to do so. The problem with high-capacity semi-automatic firearms is that they make it easy for one person to do a great deal of harm to a large number of other people at a terrible rate of speed. The goal in regulating such weapons is not and cannot, unfortunately, be to prevent every person who desires to harm other people from doing so. The goal is to limit the damage one person can inflict quickly. We cannot save everyone — we cannot eliminate danger or evil from the world — but we can save some of us. We can declare that our lives are more important than unrestricted access to an object of harm.

The problem with videogame violence, on the other hand, is that so much of it is irredeemably stupid and exists as little more than a cash grab on the part of developers through a shallow appeal to the basest instincts of its audience. This is worthy of discussion and at least critical intervention, but it is not even in the same continuum as gun violence, and it debases us to pretend otherwise. It is a stupid problem too frequently considered in stupid terms.

We need to do better on both of these issues, and if one of them is far, far more important, at least the other is far, far easier.

———

Gavin Craig is a writer and critic who lives outside of Washington, D.C. Follow him on Twitter @CraigGav.