Nonsense

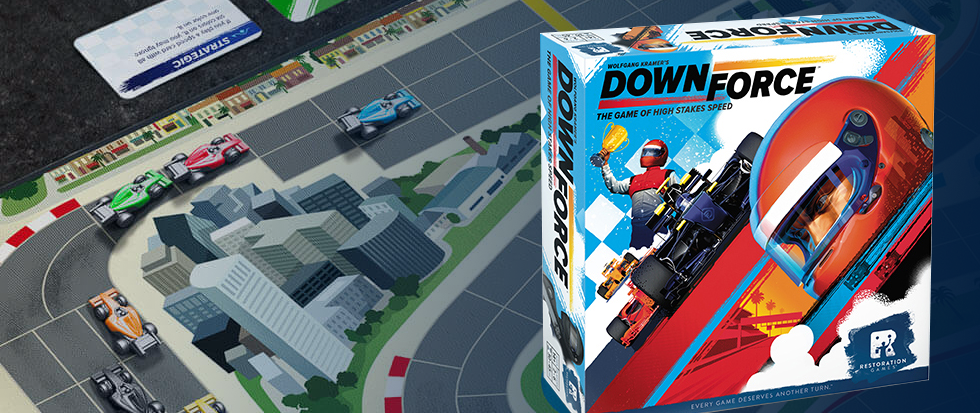

A board game scores a real thematic coup when it marries the theme of a board game to its mechanics in ways that make sense in context. We praise games where a level of immersion can be reached, but the truth is that games live in the realm of the unreal, thriving as abstractions of real-world concepts. Sometimes you just have to let chaos reign and just go with the nonsense inherent in games. Racing game Downforce is a great example of this, a fantastic auction game of racing to see who can make the most money where you control every car on the track.

Already, “control” is a multilayered concept in Downforce. Initially, you bid to take ownership of one of six different cars that each have special powers. How much you bid is deducted from your final score, which is measured in millions of dollars. Already the theme of being a race car owner comes through and is well suited for the way Downforce is scored. You want your car to do well, because you get prize money for finishing in certain positions. So far, so thematic.

This all comes undone when you get to the actual race, which is controlled by cards in players’ hands. Each card has a set of numbers and colors on it, and when one is played, each car of the corresponding color goes forward a number of spaces equal to the number by it. The trick here is that the player who played the card moves all of the cars and makes all the choices for said cars. Think about the implication here for a second. You’re playing a card that dictates how multiple cars move on the board, and then moving them all yourself. In this light, you’re controlling every car on the board. This makes no sense from a thematic perspective, because of course you expect to only move your own car, not everyone’s. But you’re shaping the entire race together, like gods from on high. It’s completely thematically inappropriate.

But in the end, it doesn’t matter because this mechanic makes for some very satisfying gameplay shenanigans. Taking control of everyone’s cars matters because you always have to move the cars forward, and if you can’t, then the car loses the remainder of its movement points. This lets you shove your opponents’ cars into inconvenient spots where they’ll be stuck while putting your cars ahead. The game gives you some flexibility as to what cars to favor, as the rest of the end-game scoring involves you betting on who will win three different times. What ends up happening is everyone trying to push forward who they think will win while trying to trap the rest of the competition behind each other. It’s uproariously fun.

It’s also a lot of nonsense. This mechanic has no basis in thematic ties except to illustrate how cutthroat and competitive races are. And yet none of this matters because the nonsense is what gives the game its spark. I often talk about how the fusion of theme and mechanics is a beautiful thing, but not every game has to adhere to that strict standard. Reveling in the nonsense speaks to the very foundations of games, from which amazing experiences are built on. Or, put more simply, sometimes you want the nonsense because the nonsense is a ton of fun.