Our Relationship With Frustration

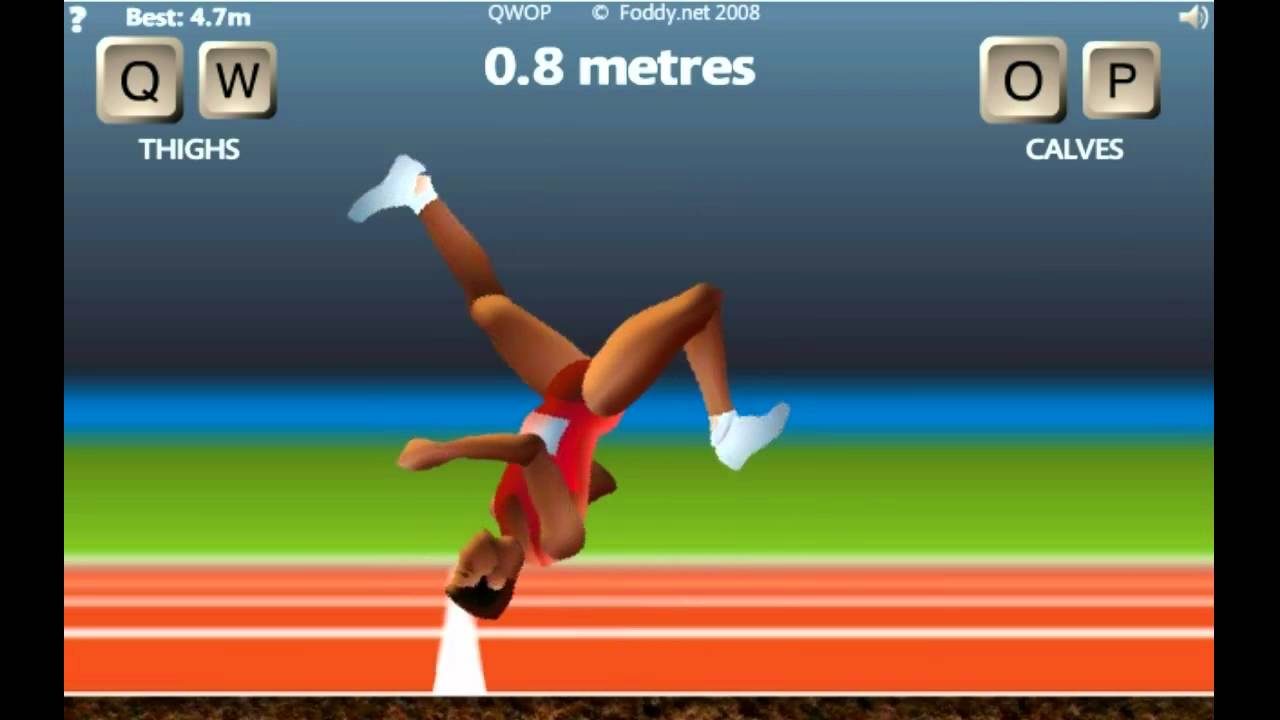

Those who know me in some capacity would see that I’m very good at videogames™. Friends and acquaintances alike have instinctively bowed down to my superior understanding of the medium whenever I pantomime tapping away at the keyboard or a controller between extended bouts of gaming, like going to work or anything else of much less consequence. That’s why I would think I’m pretty worthy of writing about Getting Over It With Bennett Foddy, the latest videogame from the creator of frustratingly brutal running simulator, QWOP, because it is a Very Difficult Game.

To be honest, Getting Over It is more akin to a life-long challenge than a videogame. Unless you have hours to spare and a boundless supply of patience, it’s quite likely most will never get to see the game to completion. As a man stuck in a cauldron and armed with the handiest of sledgehammers, your only task is to climb as high as you can, be it over rocky terrains, massive landfills, abandoned buildings, household items or even a playground. I once saw someone take eight hours to complete the game and many other streamers rage-quitting upon a major setback. And to add salt to the wound, creator Bennett Foddy even dispenses some nuggets of wisdom about embracing failure, just as you inevitably fall from a height you’ve been struggling with for the past hour. It’s grueling and antagonistic.

Frustration is a uniquely videogame experience. We play games, we screw up and then we die in agony. We tear our hair out in exasperation, scream at our screens till spittle coats the scream, and stare at our controllers incredulously as if they have let us down. A particularly relentless brand of frustration is also the hallmark of Foddy’s games and, while he usually stretches this mood to its fiendish limits, he also sees it as an integral form of motivation for most games. As he explained to Keith Stuart of Guardian, “Players who are trying to play well are typically more engaged in the game. We’re trying to build engagement, so players can have that experience—which videogames are so great at providing—of being completely immersed and involved.”

Yet, too much frustration can lose players very quickly, particularly if it’s a result of poor game design, like the impossibility of jumping from one ledge to another due to poor camera placement. Foddy’s games aren’t the most accessible—trying to get the runner in QWOP to walk is a sheer feat in itself—but his games’ sheer potential for streaming have caused them to explode in popularity. The drive to succeed against all odds is intoxicating. Watching people fail is pure schadenfreude.

But more than just the crushing sense of loss, frustration feels like failure and a destruction of our self-image. It may feel like an uncomfortable realization of our lack of skills, which, incidentally, is an incredibly touchy subject in the community. Games critic and journalists who aren’t skilled enough are deemed undeserving of their jobs. Struggling players are told to “git gud” and slammed with hostility. And according to some, only the best and the most elite get to attach the mantle of “gamer” to their identity. While undoubtedly frustrating, failing in Getting Over It doesn’t feel quite as salty. Failure in this instance isn’t tied to our self-esteem, since everyone fails. Pewdiepie fails. Markiplier fails. Jacksepticeye fails.

If failure becomes personal, then the salty taste of frustration will overwhelm your senses. Getting Over It is phenomenally frustrating, but it’s created precisely because Foddy wants you to be hurt. He wants players to experience new depths of fury they have not felt before. This frustration is intrinsic to the game design. It may say nothing of your abilities to climb a mountain of junk. You’ll be angry, but only for a while. You’ll be fine.