Vidar Is a Reminder About the Finitude of Time

Modern roleplaying games (RPGs) can be cliché, with some aping the conventions of older games that influenced them. Time becomes a limitless commodity. Heroes can immerse themselves in side quests to find their Chain Mail of Monster Slaying +10 and amply prepare for the final, cinematic battle. Everyone is waiting for someone like you—actually, just you—to help them with a personal crisis while learning a life lesson about overcoming adversity. Song and dance sequences optional.

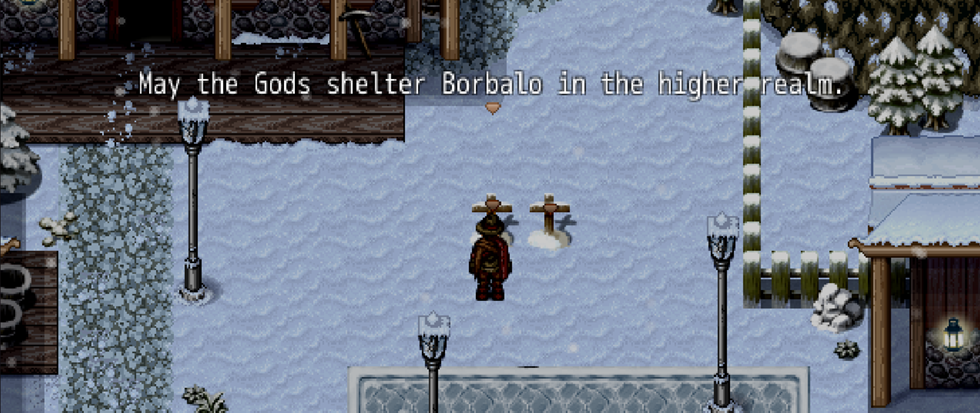

Vidar is upending these conventions. In this game, you’ll make your way to a snowbound village and meet several townsfolks, all preoccupied with their own troubles. Every night, a mysterious Beast will slaughter a random villager, which inevitably influences how the rest of the village respond to these deaths. Like a merciless version of the reality series Survivor, there are 24 days and 24 villagers. You’re supposed to stop the Beast and save the village from certain doom.

In one instance, Barnabas, a veteran wrecked by his memories of a war decades ago, passed away. Trapped between an endless blizzard and the ravenous Beast, I had to stay in town, but was shocked to find no way to prevent his death. Moreover, there’s no side quests to detract from the main plot; no peace for the troubled and now-deceased Barnabas; and no resolution for the grieving. Following Barnabas’ death, his apprentice, Etel, sunk into despair and turned to the bottle.

After every night—and the demise of yet another villager, I can make several key choices. I can help Etel combat his alcoholism in this instance, but that means squandering the opportunity to aid another villager in an equally dire situation. Like Sandor the clockmaker, who was devastated by the disappearance of his son and was imploring you to find him who, without your aid, will surely die. Trying to save everyone is an exercise in futility, and the gravity of every decision will weigh heavily on your conscience.

The discomfort resulting from the inability to save everyone, and the time limit imposed on puzzle solving, is a little like the original Fallout. In that game, the vault you live in is running out of clean water, and you’re tasked to find a chip for fixing the water purifier. As much as RPG traditions beseech you to, the limited water supply in the vault means you don’t really have the luxury of time to wander about while on the hunt. There’s a very real possibility of your community dying of thirst if you dawdle. It’s so tempting to do so though; there are dozens of wastelanders out there who need your assistance. There’s an urge to discover more about the world outside the vault. Yet, helping them all really isn’t in your favour. You have to prioritize your main mission over others.

Putting aside the obvious ludonarrative dissonance in other games (you know, that term that describes the conflict between narrative and gameplay), the helpless you experience in Vidar makes the relationships you nurture over that agonizingly short period of time even more striking. Even though losses are rampant, your decisions to help certain folks over others doesn’t render your efforts meaningless. That’s because unlike most RPGs, Vidar isn’t a game that lets you save everyone. It’s a game about consequences. It’s a game about making peace with our perennial foe: time.