Damnation & Dominion

Gavin Craig has a lot of games on his shelf that he’s never played. Backlog is his attempt to correct that.

Gavin Craig has a lot of games on his shelf that he’s never played. Backlog is his attempt to correct that.

———

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #94. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Of Mans First Disobedience, and the Fruit

Of that Forbidden Tree, whose mortal tast

Brought Death into the World, and all our woe

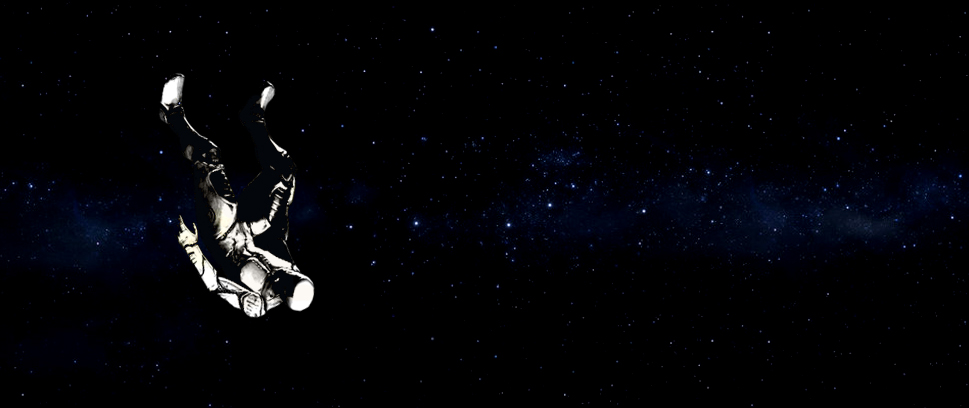

Like Mass Effect 2, Myst and Milton’s Paradise Lost, The Fall begins with a body plunging from the heavens. This body awakens in a state of innocence (to varying degrees in the various stories) and must, quickly or slowly, taste the fruit of the knowledge of good and evil. While The Fall distinguishes itself from this group in that its narrative of the acquisition of moral agency centers on an artificial intelligence (AI), this is a common theme in stories in which we imagine artificial beings.

I’ve got no strings

To hold me down

To make me fret,

Or make me frown

I had strings

But now I’m free

There are no strings on me

The tendency to center questions of innocence and moral agency is odd because nearly all AI stories are about the creation of disposable beings. Things which can be of use but whose intrinsic needs do not merit consideration beyond the requirements of utility. Objects whose intelligence primarily serves to enable them to anticipate our needs. Beings to whom we can outsource the consideration of scarcity. Such beings are not a rarity in human history.

The tendency to center questions of innocence and moral agency is odd because nearly all AI stories are about the creation of disposable beings. Things which can be of use but whose intrinsic needs do not merit consideration beyond the requirements of utility. Objects whose intelligence primarily serves to enable them to anticipate our needs. Beings to whom we can outsource the consideration of scarcity. Such beings are not a rarity in human history.

“Consider that in the history of many worlds, there have always been disposable creatures. They do the dirty work. They do the work that no one else wants to do because it’s too difficult or too hazardous. And an army of Datas, all disposable… You don’t have to think about their welfare, you don’t think about how they feel. Whole generations of disposable people.”

“You’re talking about slavery.”

“Oh, I think that’s a little harsh.”

I just spent ten minutes searching for a relevant quote from Ex Machina and had to confront exactly how much of the film is two dudes talking to each other. Even when our fictions explicitly consider the agency of an alterity, we are barely able or even interested to consider any terms beyond what it might think about us.

A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

A robot must obey orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

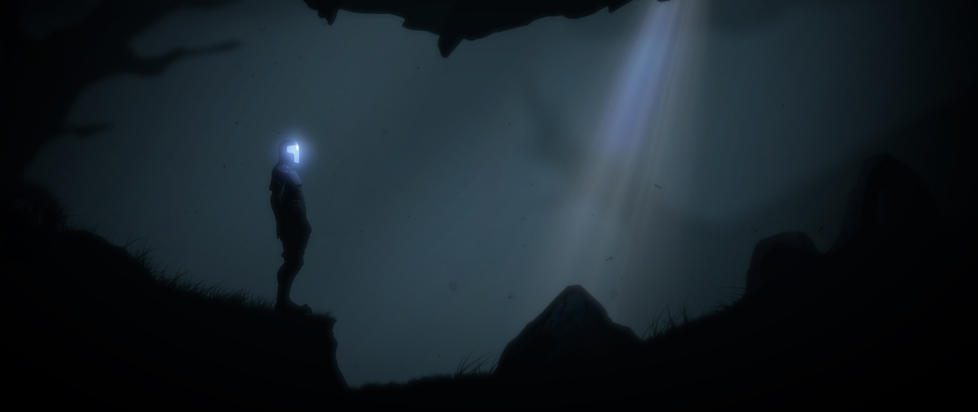

In The Fall, the A.R.I.D. Mark 7 AI is a combat suit tasked with the protection of its human pilot. As basic functional constraints, A.R.I.D.’s programming demands that it must not misrepresent reality, it must be obedient and it must protect its active pilot. To escape the underworld into which it has fallen (the quality control facilities of an abandoned domestic robot factory) and to save the life of its comatose pilot, expediency forces A.R.I.D. to perform a number of tasks that push against these constraints. Domestic tranquility requires appeasing human self-image, which cannot be performed without that essential social tool, the little white lie.

In an Existentialist twist, A.R.I.D. is eventually stripped of its purpose as well of its constraints, even if it declines to come to the conclusion that the two are really one. There is a secret that I will try to not quite reveal, which could serve to decenter A.R.I.D.’s existence as one defined by its relation to humanity except that A.R.I.D.’s discovery of that secret brings an abrupt end to the game. By treating its AI as empty when severed from a master to serve, The Fall treats A.R.I.D.’s acquisition of moral agency as an exercise in futility.

Which is to say that The Fall thinks that it is a game about doing harm in the name of doing good and never quite realizes that it is about not just the impossibility but the irrelevance of “moral agency” for beings treated as unworthy of moral consideration.

For God doth know that in the day ye eat thereof, then your eyes shall be opened, and ye shall be as gods, knowing good and evil.

Here we may reign secure, and in my choyce

To reign is worth ambition though in Hell:

Better to reign in Hell, then serve in Heav’n

We may have been expelled from the Garden, but at times, it can feel that we’re still trapped in the hell of 17th century, only able to consider morality and agency in terms of relationships of power. As long as dominion continues to drive our sense of justice, as long as we treat certain beings as disposable, we will all continue to burn.

———

Quotes: Paradise Lost by John Milton. “I’ve Got No Strings” by Leigh Harline and Ned Washington. Star Trek, “The Measure of a Man” by Melinda M. Snodgrass. The three laws of robotics, “Runaround,” Isaac Asimov. Genesis 3:5, KJV. Paradise Lost by John Milton.

———

Gavin Craig is a writer and critic who lives outside of Washington, D.C. Follow him on Twitter @CraigGav