About Gundam Time – Mobile Suit Gundam Thunderbolt Vol. 4

Despite all the pyrotechnics flying about, the first arc of Mobile Suit Gundam Thunderbolt concludes more with a fizzle than with any nuclear blast. After the climatic rumble between Gundam pilot Io Fleming and Zeonic ace Daryl Lorenz last volume, that’s only to be expected. There, author Yasuo Ohtagaki was interested in bringing the first act of the rivals’ conflict to a close; here, his interest lies in gathering all manner of loose plot and character threads the better to move on to the next phase of his story. Io escapes captivity and returns to the Federation a hero, Daryl Lorenz and his men retreat as the last bastion of the Zeonic line, the space fortress A Baoa Qu, b urns behind them, and an ominous group of space monks round up a number of stragglers, not least important among them researcher J.J. Sexton and the once-presumed-deceased Claudia Peer.

urns behind them, and an ominous group of space monks round up a number of stragglers, not least important among them researcher J.J. Sexton and the once-presumed-deceased Claudia Peer.

The rest of the volume is devoted to setting the stage as, seven months later, Io’s new unit and remnants of Zeon led by Daryl both prepare an operation to recover a newly built Psycho Zaku from the secessionist Nanyang Alliance. It’s a remarkably low-key conclusion and a slow-start to a story that has traded until now in shocking developments and cheap emotions, and yet it is also the first time that Mobile Suit Gundam Thunderbolt seems to find a register it is comfortable with.

Because, for the first time, Mobile Suit Gundam Thunderbolt seems to realize it is not the hard-boiled war-drama it once fancied itself. That it is every bit as stupid as it sounds and looks. And that stupid and energetic is not a bad thing to be if you’re aware enough to do something with these attributes. Yes, there are instances of hamfisted symbolism in these chapters treated so sincerely they make the beach-side dream sequence, miraculous lightning bolts and overly explanatory lyrics from earlier in the series seem the height of subtlety: nobody with eyes will miss how Io’s own blood stains his medal of honor after his spiteful sister intentionally stabs him with the medal’s pin.

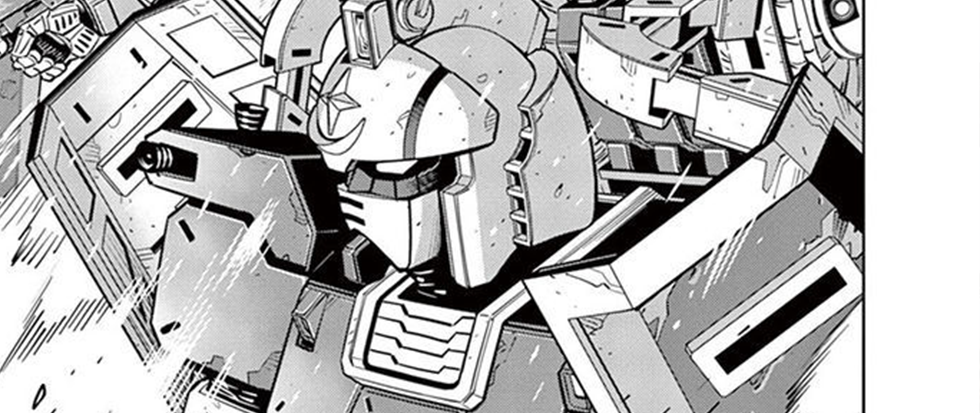

But for the first time there are sights and characters that have personalities distinct enough and valuable enough that they register. Favorably. Ohtagaki’s renderings of Earth may be of a smaller scale than any of his renderings of skeletal space colonies or debris-cluttered voids, but these beaches, these craters – with their melted cities jutting out of cliff faces like tumorous growths – possess presence. They no longer feel like the backdrop to the action but a geography that characters move in, through, and around. They feel like a world. Io’s new Gundam – the sleek RX-78AL Atlas – similarly feels more real than its overdesigned precursor ever did. Though what little conflict we do see on Earth is abbreviated this time around, the drastic changes in design and presentation suggests that skirmishes from now on will no longer suffer from the weightlesness and ill-definition that made the space battles before them pass uneventfully by.

Better still, Ohtagaki’s newfound self-awareness has brought with it a welcome sense of the absurd  impossible in the heady, edgy days of earlier volumes, and through this sense an expansion rather than a shrinking of dramatic possibilities. The introduction of the space monks – the leaders of the Nanyang alliance – at the book’s midpoint is not just remarkable for the much needed dose of strangeness it introduces; it’s remarkable because Thunderbolt Gundam’s newfound willingness to introduce the strange has also allowed it to introduce the unsettling, and no emotion could be more necessary for a good war story. The monks themselves – with their toadlike features and in their ritualistic spaceware – cut an eerie enough presence floating alongside one another in the unsettlingly perfect concentric circles of an anodyne airlock.

impossible in the heady, edgy days of earlier volumes, and through this sense an expansion rather than a shrinking of dramatic possibilities. The introduction of the space monks – the leaders of the Nanyang alliance – at the book’s midpoint is not just remarkable for the much needed dose of strangeness it introduces; it’s remarkable because Thunderbolt Gundam’s newfound willingness to introduce the strange has also allowed it to introduce the unsettling, and no emotion could be more necessary for a good war story. The monks themselves – with their toadlike features and in their ritualistic spaceware – cut an eerie enough presence floating alongside one another in the unsettlingly perfect concentric circles of an anodyne airlock.

But it is the sight of hundreds of shattered mobile suits wrapped in massive salvage nets – like the skeletons of celestial fish dragging in the nets of some intergalactic fisherman – and, later, the sight of their feeding body after body into the blaze of their ship’s engines for cremation that stand as the most arresting images the series has mustered. Suddenly, through these visions, the war comes to possess a menace it never did before even as it finally takes on the kind of schlocky character that Ohtagaki’s particular brand of macho stupidity has begged to be partnered with. The idea of a military nation led entirely by Buddhist monks is ridiculous – hilarious in the way that only sublimely stupid B-movies can be – and yet here also possesses a menace that feels unique to Mobile Suit Gundam Thunderbolt’s peculiar sensibilty. As though Ohtagaki has found a way to move beyond the grim irony that seemed his only mode until this point by fully embracing the strangeness of it all. And, in doing so, achieve a tension that blends the best of both.

There is a lingering sense throughout this fifth volume that the series was never supposed to last beyond the battle of the Thunderbolt sector, yes. The clumsy reintroduction of Claudia and the contrived decision to make Dr. Mitchum an essential plot plot device make it seem as though the battle between the kind-hearted Deryl and the sleazy Io should have ended with the former’s Pyrrhic victory over a rival whose good fortune to be on the right side of history was his only saving grace. As though Ohtagaki couldn’t wait to end on a predictably dour bit of dramatic irony. But if tarnishing an already flawed series’ end is the price paid to give birth to a far more interesting story, it’s a price best paid. I am finally excited for what Mobile Suit Gundam Thunderbolt has in store. It took long enough…