No Accounting for Taste: Freedom to the People!

Adam examines the reasons why he and the pop culture consensus differ in opinion.

Adam examines the reasons why he and the pop culture consensus differ in opinion.

———

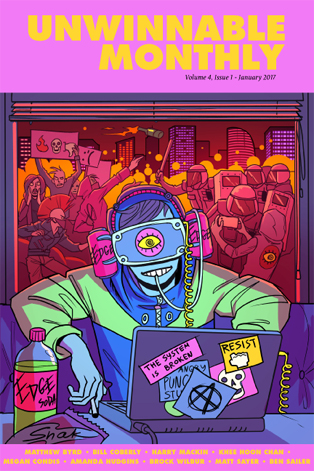

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #87, the Rebellion issue. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

In May of 1942, Stjepan Filipovi?, a member of the anti-fascist Yugoslav Partisans, was hanged by the Nazi-aligned Serbian State Guard in the town of Valjevo. Just before his hanging, he shouted, “Smrt fašizmu, sloboda narodu!” — “Death to fascism, freedom to the people!”, a communist slogan that Filipovi?’s execution lent further poignancy and urgency.

The phrase’s popularity has persisted in the years since the end of World War II and the latter half of the phrase — “sloboda narodu” — appears as both the title and last words heard on the first track of The Radio Dept.’s 2016 album, Running Out of Love. It reflects the anti-fascist impulse that drives the entire record, an album that best captured the mix of fury, frustration and despair I felt throughout 2016 as I witnessed the seemingly inevitable (but entirely preventable) rise of authoritarian nationalism in the US and elsewhere.

The Radio Dept. has always discussed politics to some extent. The “domestic scene” mentioned on the gorgeous opening track of their last album, Clinging to a Scheme, for example, probably didn’t refer to a childhood home or neighborhood but to developments the band was witnessing in their native Sweden. It’s a muted expression of aggravation with people looking to co-opt political movements for personal and social benefit. So this isn’t entirely new topical territory. What is new is the level of focus: Running Out of Love is an album of nothing but political discussion, an explicit statement of anti-fascism that also takes time to further the criticisms it began on “Domestic Scene” some six years ago.

Political commentators in the US often viewed contemporary far-right nationalist movements as specifically European. There were different explanations offered, but even as we watched, for four decades, as the conservative apparatus dragged our idea of political possibility further to the right, many found some small relief in the notion that, at the very least, we weren’t flirting with fascism. This was always too generous an assessment of the plausibility of authoritarianism in this country — and, in some cases, a denial of the oppressions, past and present, managed by our government — and in 2016 we saw clearly the falseness of this assumption.

Political commentators in the US often viewed contemporary far-right nationalist movements as specifically European. There were different explanations offered, but even as we watched, for four decades, as the conservative apparatus dragged our idea of political possibility further to the right, many found some small relief in the notion that, at the very least, we weren’t flirting with fascism. This was always too generous an assessment of the plausibility of authoritarianism in this country — and, in some cases, a denial of the oppressions, past and present, managed by our government — and in 2016 we saw clearly the falseness of this assumption.

I mention all of this because I think it is very difficult to listen to Running Out of Love without drawing immediate connections to American politics, despite the fact that the band addresses Swedish and European topics specifically throughout. Drawing political parallels between nations is a maneuver that risks oversimplification and misrepresentation, so I’ll try to be careful here, but in interviews The Radio Dept. has consistently made this international connection, recognizing these political developments as part of a greater, harrowing trend.

And while this blatant, wider embrace of authoritarianism appears to be a recent social shift, its roots are deeper and sturdier than many would like to admit. This is the context the band points to on “Swedish Guns,” a track that discusses the wild success of the Swedish arms industry, which has propelled the country to a top spot among the world’s exporters of weaponry despite its global reputation as a peace broker. Many within the country find the industry’s practices abhorrent and hope to restrict it somehow, but others see the domestic economic benefit in the manufacture and sale of weaponry as outweighing any criticisms leveled at the industry.

We hear this argument in the US constantly, perhaps so much so that it barely registers as an argument at all. Whatever catastrophes are produced, directly and indirectly, by the military industrial complex, its status as a necessary and beneficial national institution persists, and its budget continually inflates. A similar mode of acceptance applies to any number of other issues: the country’s private prison system, for example, or the systemic criminalization and deportation of immigrants. That there is profit in violence isn’t news, but what The Radio Dept. aims to highlight on tracks like “Swedish Guns” is that societal tolerance of a concept like necessary violence helped pave the way for our current crisis. The song acts as a reminder, and also an indictment, of a denial of reality that led us to this place.

It’s on the album’s second half that the band turns its criticisms to liberal political practices and the musical atmosphere becomes more despondent. On “Can’t Be Guilty,” they adopt the persona of someone who sees the oncoming fascist storm and looks to avoid it by simply trying to ignore it. The speaker asks to be left alone to sleep while the horror persists, only to be woken up when — or if — it ever ends. In this, we can hear a critique of a public unwilling to face itself, too eager to abdicate any responsibility. But I think within this and other tracks there is also a sad self-recognition and a kind of shameful acknowledgement of how tempting this idea can be.

“This Thing Was Bound to Happen” takes a more mocking tone in its verses, targeting concepts of political engagement that focus only on thinking the proper things or buying the right products. In this light, the chorus, which is just a repetition of the title, could be heard as a sarcastic attack on those who did nothing to stop the reactionary wave and who now say it was unavoidable. As with “Can’t Be Guilty,” though, I hear the band grappling with something more difficult on the track (though that criticism may be part of it). In the chorus there seems to be something like resignation. In consideration of how much atrocity has been deemed acceptable throughout the histories of Western nations deemed “developed,” the idea that the reemergence of fascism was bound to happen seems to make sense. There is almost no inhumanity that has not been excused or justified in the service of protecting political stability and wealth accumulation for the ruling class and those who identify with it — a narrow, white demographic. That this would one day lead many of these people to consider a rebranded form of authoritarianism their only reasonable political option should not be as surprising as many observers found it to be.

“This Thing Was Bound to Happen” takes a more mocking tone in its verses, targeting concepts of political engagement that focus only on thinking the proper things or buying the right products. In this light, the chorus, which is just a repetition of the title, could be heard as a sarcastic attack on those who did nothing to stop the reactionary wave and who now say it was unavoidable. As with “Can’t Be Guilty,” though, I hear the band grappling with something more difficult on the track (though that criticism may be part of it). In the chorus there seems to be something like resignation. In consideration of how much atrocity has been deemed acceptable throughout the histories of Western nations deemed “developed,” the idea that the reemergence of fascism was bound to happen seems to make sense. There is almost no inhumanity that has not been excused or justified in the service of protecting political stability and wealth accumulation for the ruling class and those who identify with it — a narrow, white demographic. That this would one day lead many of these people to consider a rebranded form of authoritarianism their only reasonable political option should not be as surprising as many observers found it to be.

The album’s final track, “Teach Me to Forget,” dives into a deep melancholy, maybe echoing some of the sentiments of “Can’t Be Guilty” with its desire to turn away from the reality in front of us. It evokes a hopelessness that feels familiar and unfortunately comforting. This is the rut I find myself in so often lately, and the song seems like an appropriate closer to a discussion about the modern fascist reshaping of societies. It’s a weary and miserable surrender, an admission of an urge to put all of this out of mind, somewhere it might be quietly ignored.

The task, for me at least, is to perpetually remind myself of the defiant spirit of the album’s opening track, “Sloboda Narodu” (something millions of people have been doing, often out of necessity, for generations). It’s interesting that the first half of the track’s title phrase — the “death to fascism” half — isn’t included in the song anywhere. Technically, this is because the band wrote the track as a companion piece to an earlier single, called (unsurprisingly) “Death to Fascism,” which situates itself entirely around a looped recording of the original expression. Reusing the audio for the album track probably seemed unnecessary. In the greater context surrounding the album’s release, though, we can also understand the first half of this slogan as always being implied. Even when it isn’t stated outright, it is recognized. The pursuit of real freedom should always and necessarily lead to fascism’s defeat.

———

Adam Boffa is a writer and musician from New Jersey. You can follow him on Twitter @ambinate