They Could be Monsters, For All You Know

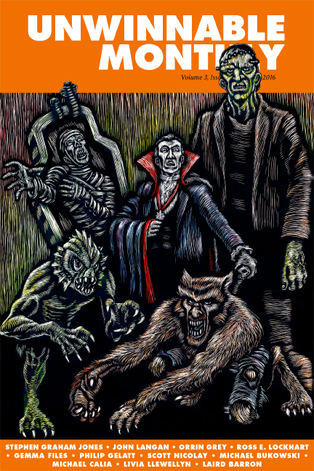

This essay is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #84, the Monsters issue. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This essay is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #84, the Monsters issue. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

It’s three in the afternoon, and I’m writing this from my childhood bedroom. Yesterday I flew from Newark Airport into Sea-Tac, and took the long drive down I-5 into Tacoma. From the car window I watched as the thick forest of evergreens lining the freeway morphed into car dealerships and casinos, then into the neat gray skyline of downtown Tacoma, and finally into the cedar-shingled mid-century homes of my suburban childhood. My bedroom is much the same, so is the house and surrounding neighborhood. I look out the window past the forty-five-year-old curtains and see the same impenetrable masses of rhododendrons, the same bristling black telephone wires, the same blue-gray sea of the northwestern sky.

Later on, I’ll sit in the living room, watching my mother read her paper by the dim, thin light of the afternoon sun. If I close my eyes, I could be all alone, with only the tick of the clocks and the hum of the refrigerator breaking the silence. I’ll go outside and walk a stone path into the middle of the backyard, listen to the wind hissing its way through towering evergreens. Cars will drone in the distance. Crows will gather at the roof’s edge and scream. I’ll turn in a slow circle, staring at the darkened windows of the houses across the fence. Rain will start to fall again, and I’ll go back inside. The rest of the day will pass in equal silence — only at night, long after my parents have fallen asleep, will I turn on the radio, listening to the sounds of a world that might as well be a million miles away. Slipping from my room, I’ll creep through darkened hallways and rooms, making my way to the garage. There, in the heart of the house, I will turn once again in a slow circle, staring at the car, the freezer, the tool cabinets, the luggage, the lawn furniture, the blackened furnace — all the things that gave been here since I was ten. Outside, a dog will howl. If it is the same dog that howled when I was ten, I would not be surprised. Nothing has changed here in fifty, sixty, seventy years. It’s as if I had never left to live another life.

Then again, that’s always been the entire point of suburbia: nothing changes, nothing is left to chance, and everything beyond its borders is diminished in impact or altogether nonexistent. You move through the streets and intersections in a sort of artificial state of mind, guided and controlled by an unnatural configuration of perfectly planned streets and manicured landscapes and inoffensive architecture that has no relationship to the outside world. Wilderness has been plowed and burned away, and all the curving wild beauty and mysterious wonder of nature has been relegated to the pale, thin outline of the mountains five hundred miles away, the mountains that you only see when you climb the rooftops with your friends and drink beer while watching your high school’s football team play under bright lights and falling rain. Everything is brightly lit here. At night, there are street lamps and porch lights, night lights in bathrooms and the bioluminescent glow of computer and television screens. Every aspect of your surroundings has been designed for perfection, for a worry-free life. The blacktop is smooth. The neon signs have all their letters intact. All of the supermarket produce is beautiful, without a single blemish or wound. There are no cracks in the paint. Everyone looks the same, although your environment was designed to isolate each of you in plain sight of the other — you rarely see who your neighbors actually are. They could be monsters, for all you know. You have no need to dream in suburbia, because if you are here, you have achieved all your dreams. Of course, we all know what happens to the human mind when it is unable to dream. It’s the same thing that happens to the wilderness. It pushes back. Some things cannot be controlled or contained. If you empty the life out of something, the vacuum will someday refill. If you exorcise all ugliness and imperfection, they will eventually find their way back home. They are, after all, just like you.

In suburbia, horror is a mold. It blooms into life where you cannot see it, eating through wood and floating through air, working its way through plaster and transmuting water into a nursery of wriggling spoors. It is ordinary at first, routine—perhaps you do not even see it as it darkens your walls, subsumes your plants, settles in your lungs. Events and instances, perfectly ordinary, occur throughout the hours, the weeks, the years. Nothing you can put your finger on that is in any way a deviation from your engineered life. Nothing happens that can be held up as proof that malformation and rot have occurred, that the wilderness is not returning to reclaim its stolen land. And yet. And yet.

Perhaps you are sitting in your kitchen late at night, listening to the house settling into its foundations as you flip through muted channels or the pages of a book. From the garage, the furnace sighs and moans, and a rush of air whispers to you from the vents. Was that a voice? Did someone just speak? You stand up and listen in the dim gloom, waiting. It’s just the air — the heat turned off hours ago, but you know it’s just the air. How could it be anything else? The clock on the wall softly ticks. Another low, feathery sigh, followed by hushed words. The hairs prickle on your arms. Did that come from the corner behind the hutch? You stare. You stare. Something in the walls . . . you finally sit back down, unnerved into frozen silence, and the minutes bleed away into black night as your tea grows cold, as your imagination sparks into life like a terrible, ancient machine.

Or, perhaps you are washing the dishes, looking out the kitchen window at the neighbors across the street as they get out of their car. There are gestures, silent words, the slam of the front door. A few minutes later, you see movements through their back yard, partially obscured by fences and trees. The husband? You cannot be sure, but the wife is unloading groceries from the car, so. Another movement: curtains parting in the upstairs window. A face, malformed and misshapen, presses against the glass. Your heart skips a beat as the dish slides from your hands into the soapy water. You don’t know the couple’s names, but you know they don’t have children. Or do they? Large eyes swivel down, and now a hand is sliding up — good god, did it see you, is it waving at you? You rip your hands out of the water and violently yank the curtains shut. Later, when you’re putting the dinner dishes in the sink, you turn out the lights and open the curtains a smidge. Soft lemon light surrounding the silhouette of a person. It hasn’t moved. Probably some crafty decoration, you tell yourself as you back away from the unwashed dishes. A wreath or a scarecrow, even though it isn’t fall.

Scores of neighborhood children circle an object on their bikes in the late afternoon sun, chanting as they pelt it with rocks and sticks. When they scatter and dart past you, their grins seem impossibly thin and wide. Were those extra teeth?

One of the teenage girls claims she saw a wolf rise up on its hind legs and walk across her lawn—other girls have seen this, too, they’ve all seen the beast peering into their bedroom windows at night. Her parents search her bedroom for drugs.

Secretly, the mothers gather over morning coffee and tell their own explicit tales of the creature.

The foreclosed house at the end of the street, have you seen the lights flicker on and off at night?

They say the family in the ranch house, the one hidden behind massive hedges, are all related. You can see it in their eyes.

Five dogs disappeared on the next street over. All the collars were found hanging on doorknobs.

The trees toss and crack as if they’re being split in two, but it’s not windy today.

There’s a face in the corner sewer drain.

It’s so boring here, and nothing ever happens. When you turn on the radio or TV, what you hear is what’s happening somewhere else, to and for people who are not you; and the music and images serve only remind you that you have failed, utterly and totally, and everything in your life is nothing more than a massive hand pushing you just below the surface of the water, where you can never quite fully breathe. Today is like yesterday is like tomorrow is like every year you’ve ever been alive, and you would slather your body in the blood of the monster you know lives in your crawl space and run out into the street and scream until the skies split open, but everyone has cable and high speed internet, so no one would hear you. Something is wrong, terrible and horrible things are happening but who can you trust, and all your neighbors just roll their eyes and gossip about you even as they tell the same stories to each other, because they all know, they’ve all seen, it’s happened to them. And it’s too late anyway, because aren’t your front teeth growing a bit longer and sharper, and didn’t you vomit up your breakfast the other day only to watch shining crimson centipedes scatter down the drain, and weren’t you so stupid to not believe before it also happened to you. And your mother or brother or daughter hasn’t come out of the bathroom in a week, and you know they’re still alive because you can hear them, but you don’t think they’re your mother or brother or daughter anymore. No human mouth should make those wet, popping sounds.

And the mail is still delivered, and the papers appear on the porches, and people further down the street or on the next street over still go to work and catch buses to school, and bring groceries home, because this is suburbia and suburbia was not built for change. And people move out and empty houses rot in place, and blight and despair eat away at everything until the rows and rows of houses are nothing more than the crumbling teeth of a surfacing leviathan, and nothing is done because this is suburbia and suburbia was not built for change. The wilderness has returned, it fills up all the spaces it had been plowed away from, but the forms it now takes in this reclaimed space is nothing like it has ever been forced to take before; and your dreams have returned but they are nothing like the dreams you have beyond these unnaturally quiet streets and yards and room, because you are suburban and nothing in suburbia was meant to change. You have come back home and sit in your childhood bedroom and try to write, but against your will your gaze slips away as your fingers freeze against the keys, and all rational thoughts and all life as you know it where you live now slip away as you stare out at the front yard trees you once read under, at the street where you skinned your knees, at the house across the way, still painted the color of rotting cream. Something in the second story window stares down at you, unmoving, pale face pressed against the glass, one multi-fingered hand sliding up and down. It could be a decoration, a doll propped against the sill. It could just be a boy.

You know what it is. You know.

———

Livia Llewellyn is a writer of dark fantasy, horror and erotica, whose short fiction has appeared in over forty anthologies and magazines and has been reprinted in multiple best-of anthologies, including Ellen Datlow’s The Best Horror of the Year series, Years Best Weird Fiction, and The Mammoth Book of Best Erotica. Her first collection, Engines of Desire: Tales of Love & Other Horrors (2011, Lethe Press), received two Shirley Jackson Award nominations, for Best Collection, and for Best Novelette (for “Omphalos”). Her story “Furnace” received a 2013 Shirley Jackson Award nomination for Best Short Story. Her second collection, Furnace (2016, Word Horde Press), was published this year.