Dead-End Narrative

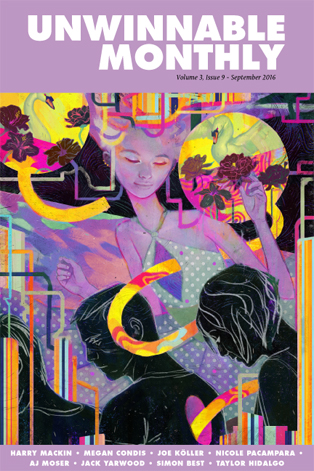

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #83, the Love issue. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #83, the Love issue. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

“I just need to blow something up.”

Older board games like chess, parcheesi and checkers were about outwitting and strategy. Even a game like Jenga, for which destruction was its inevitable end, relied on players showing restraint and care rather than a reckless desire for the tower’s ruination.

As early as the very first videogame, demolition was introduced. From Spacewar on, players have been playing videogames largely as an opportunity to take out their aggression on the enemy. Since Cain slammed Abel over the head with a brick, it seems, we’ve been itching for a safe and secure way to express our disdain for one another through less harmful means.

Maybe that’s why we so often praise a videogame’s “visceral” experience, i.e. one that appeals more squarely to our gut than our rational or relational centers. Rather than appealing to our love and desire for one another, games have for a long time allowed an exploration of our lizard brains. If we desire to burn it all down, videogames have provided a place.

It isn’t just hyper-violent games like Mortal Kombat and Doom that made this a reality. What is clear when one looks at the history of the medium is that the baseline violence of videogames has always been present, but became unmissable once graphic capability made it possible to depict realistic violence on-screen. All of a sudden, we could recognize the spine. And we loved it, for reasons we didn’t quite understand.

Game developers, like Jerry Springer, porn producers and N’Sync, gave the people what they wanted. Games became self-aware of their violent tendencies and leaned into them, creating entire genres created around violent concepts: shoot-em-ups, fighting games, first-person shooters and so on.

Theoretically, the violence would become mundane, but a game is not a part of a longer narrative when one plays it. In the moment, a game is all-consuming and the player embodies and embraces the goals and assumptions of that game.

So, we embraced and embodied destruction over and over again, never seeing it for the dull, mindless, mundanity that it really is. Cain chose the most basic way to solve a problem known to man. He lacked the most basic form of creativity. Cavemen kill.

Habits matter. One violent game among a host of other types of game can be healthy. It can be a convenient way to blow off steam, but constructing for one’s self a lifestyle of violence leads not so much to the dull “desensitization” your mother warned you about.

It’s more sinister than that, I think. In a world full of challenges, when our lives are defined by one obstacle after another, violence is a dead-end narrative. It’s a way of giving up and still winning, which is to say, it is existential cheating. Violence is lazy. Violence is giving up hope. Violence is a vacation at the beach.

But a vacation at the beach is not living. And violence is not life.