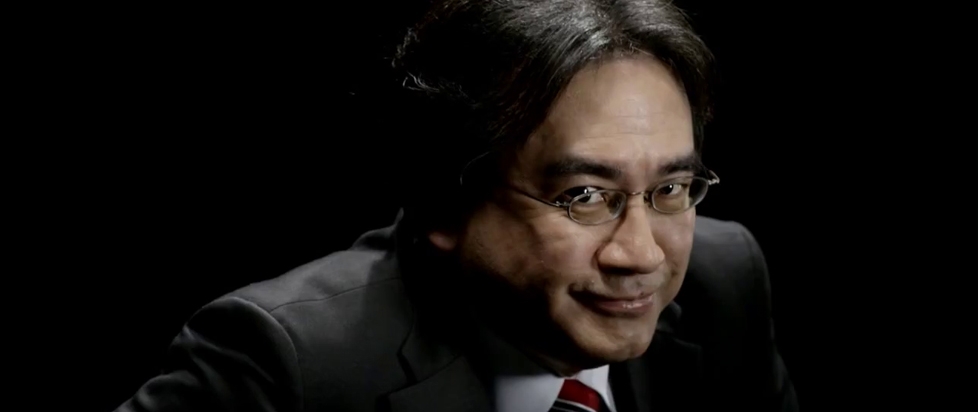

Who Was Satoru Iwata?

The following is a reprint from Unwinnable Weekly Issue Fifty-Three. If you enjoy what you read, please consider purchasing the issue or subscribing.

———

Early last summer, I had a conversation with some colleagues about Nintendo. We were talking about how tightly guarded all information is kept at videogame companies. We don’t know what we don’t know. We only know what we’re deemed worthy of knowing, and only as the next drip of information to spike anticipation splashes, reminding us of our next purchase in a selective one-sided conversation.

Early last summer, I had a conversation with some colleagues about Nintendo. We were talking about how tightly guarded all information is kept at videogame companies. We don’t know what we don’t know. We only know what we’re deemed worthy of knowing, and only as the next drip of information to spike anticipation splashes, reminding us of our next purchase in a selective one-sided conversation.

Our conversation was somber and dubious. We closed the topic by noting that when higher-ups at Nintendo started to die, it was unlikely people outside the company would know who contributed what and why it mattered. Decades of knowledge perhaps gone undocumented or just filed away or deemed irrelevant because while it was a step along the way, it wasn’t the final one in selling a product to a customer, so who cares?

Not to harp on Nintendo – but if you’re reading this, you likely know why I’m holding here – but we know they hold onto some of this stuff. Case in point: last month at E3, in a promotional video (natch) for Super Mario Maker, designer Takashi Tezuka and Mario creator Shigeru Miyamoto unfolded large sheets of graphing paper used to hand-draw and design the original Mario game. Colored pencil. Overlays of tracing paper because whiting out mistakes was “too messy.” Lots of blogs picked it up and wrote things just rewording what’s in this paragraph.

There are two things ironic about this.

One, that 30 years later, a debate still persists about the date the original Mario even came out and, two, this game came out 30 years ago – how is it possible none of us knew this before?

Mario is iconic. Even people outside the veil of videogames know who he is. And Nintendo has not been shy about reminding us when he has an anniversary – but anniversaries that don’t mean much are hollow. Flash back to 2010’s Super Mario All-Stars Limited Edition, which re-released 1993’s bundling of four early Mario games. The “limited edition” refers to the supplemental goodies like a CD soundtrack with things like a five-second track with the sound of getting a 1-up mushroom followed by four seconds of silence, a 32-page booklet with schematics of levels obscured by pictures and interviews with Miyamoto and others that had been lovingly wood-chipped down to one-liners per subject.

We don’t know what we don’t know.

That’s a phrase that came to mind again when Nintendo President Satoru Iwata died at 55 earlier this week. The official statement from Nintendo was terse – it would have all fit on one line if the sentence, “Nintendo Co., Ltd. deeply regrets to announce that President Satoru Iwata passed away on July 11, 2015 due to a bile duct growth,” had one fewer word in it.

Everyone has their own way of grieving and dealing with unfortunate news but I noticed something about the obituary posts cropping up over the Internet in the wake of this news on Sunday: most of them fit on my iPhone’s screen without needing to scroll. On Monday, some lengthier obits went up, but I wouldn’t say they’re substantive or insightful.

Who was Iwata?

Except for one obit I read – and I spent hours last night (I’m writing this Tuesday) reading and watching video tributes – everyone speaking of Iwata’s death admits they’ve never met him personally. They quickly conflate Iwata, the man, with dissemination of a spreadsheet of sales information or tough management decisions. They’re all careful to use language like “Iwata appears to,” and then drawing some conclusion from speeches he gave or sound bites that have accumulated over the years.

That’s all we got. That’s all we had.

Who is Iwata?

***

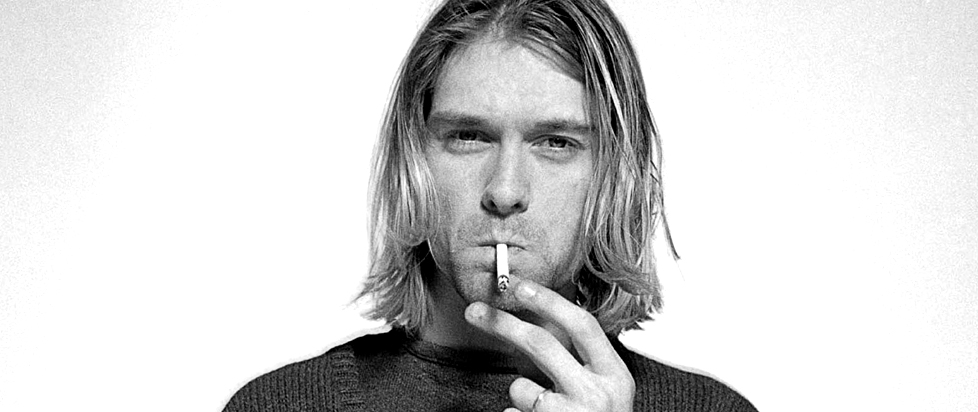

I used to think a lot of the secrecy in the games industry had to do with its origins and Japanese business practices. If you were skilled or devoted enough to beat some of those original Nintendo games, before being thanked by the credits for playing, you were treated to a cavalcade of aliases.

As legend had it, some game companies refused to let their best creative talent disclose their real names, so as to discourage poaching in a then-burgeoning industry. A colleague of mine not involved with videogames emailed me yesterday, saying he thinks about devs hiding their names in old games “probably more than I ought to.”

It isn’t just people who spend a lot of their time pondering videogames who wonder about what’s behind the curtain.

It’s a little haunting how videogames – things meant to be fun, for everyone – through their creators’ inability to speak or be fully-formed has enabled them to be the perfect blank canvas for whatever the audience would like to think videogames are or aren’t.

I mean, think about it. How much do we really know about Miyamoto? Over the years we’ve gleaned that Zelda is based on his childhood, exploring woods. He likes fitness. Dogs. No more information, really, than what you’d see as character bios from the manual in Street Fighter II. The same is true of others still around from those days of gaming – what do we really know about Hideo Kojima? That he likes movies? Food? For more current examples as an exercise: What about Clifford Bleszinski or Todd Howard?

This is the nature of fame, as managed by big, big hardware and software companies: You are your output and little more. The bigger you get, the flatter you need to be as an entity. It makes it easier to use you as a platform, in a practical sense. The bigger and flatter you become, though, the bigger a shadow you cast over everyone else’s contributions on the same output.

But part of being a fan of videogames is wanting to know more, and it’s frustrating in videogames when we’re kept at the gates of information that only open for sales information about products. I don’t mean to repeat myself, as this is familiar terrain for me. It’s just that in the wake of Iwata’s death, and the resulting coverage, it struck me how precious little information is really out there.

Many of the obit posts I mentioned above were so short they beefed up by scooping reactions from social media, a mish-mash of tribute drawings, the phrase “all the feels,” and talking about what Nintendo’s games meant to them, then dumping them out as if all together it could somehow say something more with so little input from the source.

The comments for a lot of these posts, also, were a little disturbing and cold. Regardless of the site, the template that I saw emerge was a quick showing of respect, and then a couple sentences about how this was the perfect opportunity to shake up the company’s business strategy. How they can “finally” approach the market differently, using Iwata’s death as leverage or a runway.

Like I said, everyone grieves in their own way.

But the omission of humanity behind videogames has let some pretty strange stuff brew in the oxygen and on the roads we all share.

Originally this week, I was going to write about this very strange videogame conference I attended last week for academics. That is, a conference geared towards the discussion and rationale behind deploying videogames in the classroom as educational tools – stuff like Math Blaster or whatever you’re imagining, but also the many decades of advancement that have been made in this particular stripe of the industry.

Anyway. In a panel on Diversity in the Design of Pokémon, the two co-presenters explained this was a paper they had submitted about the variety of play styles the Pokémon games have given its players over the series, and how in this subculture of gaming, there is no warring over which style is the “best.”

If you want to compete in Pokémon beauty pageants, that’s seen as just as viable as the obligatory catching of all Pokémon or any other mode. They also touched on diversity in the types of playable and non-playable characters, and how the games have always done a good job of portraying a varied world.

As they wrapped up their paper, a hand went up the row in front of me with the same question that I wanted to ask: “Why didn’t you reach out to anyone who’s worked in the Pokémon games for comment on your paper?”

The presenters made a point of saying they hadn’t talked to anyone, and if you’re wondering: Yes, it had been accepted.

I didn’t write down the exact answer, but it was stammering and it shrugged off the question. The gist was that the people directly involved weren’t relevant to their research.

The presenters were wrong.

I know firsthand how difficult it is to get people involved with videogames to talk openly and freely, outside the confines of a studio visit and with PR people present. But it’s doable. You have to ask, and you have to ask the question correctly. You have to demonstrate you’re worth talking to and can be trusted.

You have to try.

Not even asking and playing up and off how much stuff there is online already doesn’t mean everything that’s out there needs to be out there. Instead, it plays up this notion that we should just dutifully study this Allegory of the Man Cave. That the loudest, most braying, most small-minded and most obnoxious among us should be listened to the most just because they’re producing the most by sheer volume and it’s intimidated others into falling off or growing more and more quiet.

Otherwise, we risk myopia. Losing our specious ties to reality.

You’ll be like another presenter I saw at this conference: Trying to make the case that “game creators as content creators” is a new phenomenon – based on a sample size of seven. That is, seven students this professor already knew because they were already in the backyard.

That hesitancy to reach out into circles that aren’t your own can lead you to conclude games are a more potent source of inspiration than they’ve ever been, leading teenagers to astonishingly doodle Batman in their notebooks or write songs about Sonic and Mega Man, a revisionist history where kids didn’t grow up devoting their down time to demonstrating their appreciation for games in as many different ways as they can imagine.

It’s that sort of ostriching that leads a crowd in attendance to shrug and accept it as a new finding because someone says so. I mean, they did the research, right?

None of this has anything to do with videogames, despite what the blank canvas has allowed itself to be marked by. There’s a temptation to preserve videogames as magical things just because we don’t know how they’re made. But we all grow up.

We stop thinking movies are magical when we realize the blood was corn syrup and we could see the strings. Somehow, in videogames, though, you see people deep into their thirties who have never seen anything other than the magic.

It’s okay to preserve the magic, but don’t let it completely envelop you.

Have you ever heard of Otherkin? The link describes it like this:

[It refers] to people who claim that they are, at heart, something other than human. The term can either exclude or encompass those that identify as animals that have verifiably existed on this planet (called therians), but always includes everyone who identifies themselves as something other than human, including mythological creatures, extraterrestrials and inanimate objects.

Some otherkin suffer from psychological discomfort due to feeling trapped in the wrong body. Reportedly, some even experience psychosomatic symptoms of sensations in non-existent wings, tails and other body parts.

Otherkin have been called one of the world’s most bizarre subcultures…

Ok. So what does this have to do with videogames? No matter how ridiculous this might sound, the omission of letting people behind videogames be distinct and known has allowed a subculture of people to believe studio heads or top-level talent like Kojima, Miyamoto and all the rest to be Otherkin – and that game companies house Stargate-like portals with which these evolved creatures can pluck our next videogame adventures as they ordained from another dimension.

I’m not making this up. This is what a friend who used to work at a soon-to-be-defunct big game company told me has made his life a living hell for a good, long while now – that his choices producing big-budget videogames have been out of step with what his governing Otherkin overlord ordained on PlayStation 2 games.

I suppose us not knowing what we don’t know cuts both ways.

But I know this: Iwata was just a man. I wish videogame companies would trust us to see beyond the magic a little bit to know what kind.

———

David Wolinsky has opinions about videogames. He’s the creator of don’t die, a videogame-industry confessional forum and the co-producer of The Electric Cybercast II: Online, the world’s only podcast about videogames. Support his Patreon and follow him on Twitter @davidwolinsky.