Purely and Simply Evil

Even if you haven’t seen Halloween, you’ve seen Halloween.

Way back in 1978, John Carpenter put his stamp on the horror genre and directors have been imitating, riffing on, remixing and plain old ripping him off ever since.

Halloween, The Exorcist (1973) and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) form the foundation of modern horror films. An unholy trinity, if you will. While Tobe Hooper’s transgressive violence and William Friedkin’s psychosexual horror pushed the boundaries of what audiences could expect on the big screen, it was John Carpenter that developed a basic formula for horror that would play out, for better or worse, over and over again.

The plot is simple: a lunatic escapes his asylum to return home to kill again. That’s it. Of course, his preferred victims are teenage girls (though a boyfriend and a family dog both run afoul of him) and his psychologist, who is convinced of his absolute evil, is out to stop him. There are no twists. The killer kills until he is stopped. And even then, as it is implied at the end, only temporarily.

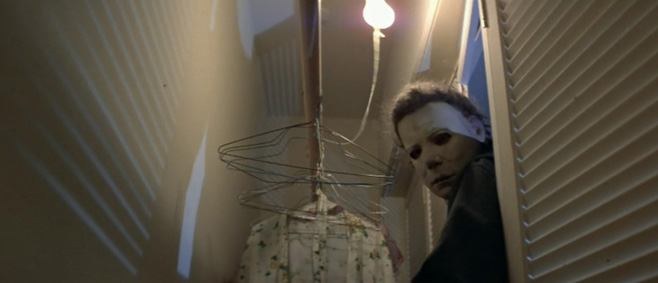

Here for the first time is the killer as a force of nature. In fact, the Shape (as he is referred to in the credits) may be something more than human. Bullet holes and stab wounds are minor obstacles to his murderous intentions. Dr. Loomis insists that some dark force resides within the Shape and this imperviousness lends credence to his claims. As with many of Carpenter’s antagonists, the Shape unsettles us in a way similar to the Uncanny Valley – its outline is human but we perceive a wrongness lurking below the surface.

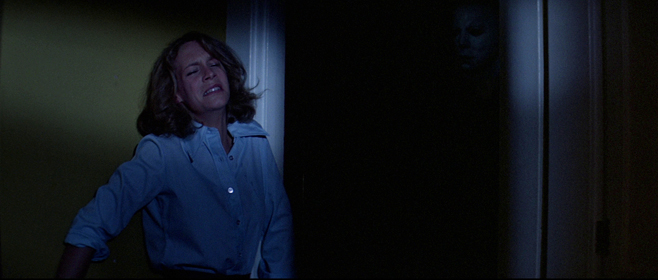

Here, too, is the prime example of the horror movie as morality play. Jamie Lee Curtis’ Laurie Strode is the lone teenage survivor of the film. There are two differences between her and her friends. First, Laurie is a conscientious person. Aside of smoking a bit of reefer early on, she doesn’t indulge in the promiscuous behavior of her friends. She doesn’t even have a boyfriend. Second, and more importantly, Laurie endangers herself in order ensure the safety of the two kids she is babysitting.

Part of this moral component has echoed down through endless slasher flicks that reward virginal heroines while punishing miscreants with sticky ends, even as it confusingly rewards viewers with lurid glimpses of nudity and violence. Derivative films chose to focus on characters’ sex lives in order to make moral judgments to such a degree that it became one of horror’s cardinal “rules” in Wes Craven’s Scream, but it is actually Laurie’s roll as a protector of the defenseless that makes her moral character.

Halloween’s greatest legacy, though, is the craft of its construction. While I find some horror movies more frightening or more interesting that Halloween, I can think of none that are so methodically well-made. In this, Halloween is the finest horror movie ever created.

Part of this is down to the fact that Carpenter borrows much from the visual language of earlier suspense films, particularly Hitchcock. Only one scene, when the headlights of a car illuminate the ghostly figures of asylum escapees wandering in the rain, looks like a horror movie to my contemporary eye. After that, the movie shifts to cultivating a pervasive sense of menace through the use of a voyeuristic first-person camera and patient, lingering shots.

As the audience is introduced to the town of Haddonfield and its residents, the Shape lurks behind bushes and drives slowly by children walking home from school, the paranoid strains of stranger danger made flesh. In one scene, we watch Laurie walking down the sidewalk, away from the camera, singing to herself. After a moment, the Shape’s shoulder enters the right side of the frame. He is watching her and, by extension, so are we. Sharing eyes with a murderer is unsettling and this sensation is amplified by how the camera loiters, longer and longer than we expect.

When the Shape begins to kill, there is a distinct lack of graphic violence – the only blood in the film is in the first few minutes, when young Michael Myers murders his sister. Co-writer Debra Hill said their intention was for the film to act as a jack-in-the-box, but these aren’t modern-style jump scares. They surprise, yes, but the mounting fear is derived again from the patience of the camera: when the Shape stands, head tilting back and forth as he contemplates a victim impaled to a wall, or, when his masked face slowly materializes out of the darkness of a doorway behind a crying Laurie. That last one has yet to be topped in the 35 years of horror cinema since.

I wonder what Alfred Hitchcock would have thought of Halloween, or of Carpenter.

There’s an obvious connection between the two directors: the former introduced Jamie Lee Curtis in Halloween and the latter cast her mother, Janet Leigh, in her most famous role as the controversial Marion Crane in 1960’s Psycho. There are a handful of Hitchcock references that Carpenter wrote into the script, too – the young Tommy Doyle, played by Brian Andrews, is named after Lt. Detective Thomas Doyle, police officer in Rear Window, and Donald Pleasance’s Dr. Loomis shares his name with Sam Loomis, Marion’s boyfriend in Psycho. There’s also the similar approach Carpenter took in directing Halloween.

More than anything, though, I wonder if Hitchcock would have realized that, like Psycho, this was a movie that would change the language of horror and suspense for generations to come. I wonder if he would have shuddered to see the Shape that stalked Haddonfield.

———

This is part of an ongoing series of essays looking at the horror films of John Carpenter. Previously, I looked broadly at Carpenter’s life and career. Next, I tackle The Fog. Feel free to disagree with me on Twitter, @StuHorvath.