A Conjuring Beyond the Mountain

David Lynch’s 1984 cult classic Dune is a flawed and fascinating movie that managed to capture my imagination while confusing the hell out of me decades ago. Other than the flawed SyFy Channel miniseries and some video games adapting Frank Herbert’s books. Who would have thought that my coincidental discovery of the topic of director Frank Pavich’s recent documentary Jodorowsky’s Dune would occur after a random balmy midnight screening at The IFC Center in Manhattan?

When I saw a restored print of Alejandro Jodorowsky’s insane 1973 movie The Holy Mountain back in 2007 I didn’t know what to think. The movie is essentially a dream, a dirty nightmare and a spiritual acid trip tied around a stick of live dynamite. So many specific elements of the movie are buried in my subconscious, much like they were almost 20 years before when I first saw David Lynch’s Dune. Not long after watching The Holy Mountain I read the science fiction author Harlan Ellison’s movie review collection Watching, where he goes into depth about the David Lynch version only after going on about another ill-fated production that never happened back in 1974. This was to be a version of Dune directed by none other than Jodorowsky himself, and it was meant to be his follow-up to The Holy Mountain. It was at this point that stick of dynamite exploded, and I had to learn as much as I could about this film oddity.

When I saw a restored print of Alejandro Jodorowsky’s insane 1973 movie The Holy Mountain back in 2007 I didn’t know what to think. The movie is essentially a dream, a dirty nightmare and a spiritual acid trip tied around a stick of live dynamite. So many specific elements of the movie are buried in my subconscious, much like they were almost 20 years before when I first saw David Lynch’s Dune. Not long after watching The Holy Mountain I read the science fiction author Harlan Ellison’s movie review collection Watching, where he goes into depth about the David Lynch version only after going on about another ill-fated production that never happened back in 1974. This was to be a version of Dune directed by none other than Jodorowsky himself, and it was meant to be his follow-up to The Holy Mountain. It was at this point that stick of dynamite exploded, and I had to learn as much as I could about this film oddity.

Flash forward to about three months ago. I’m randomly reading something on The A.V. Club when I see that a new documentary, Jodorowsky’s Dune, was tearing up European film festivals. It is an understatement to say that I was eagerly awaiting to see it when it finally opened recently at Film Forum in Manhattan. My verdict? If you’ve never given a shit about anyone or anything that I mentioned in the paragraphs above you should still see this documentary. Because at the end of the day this is a movie about imagination.

Essentially about Jodorowsky’s quest to assemble a dream team of creators and contributors (“Spiritual Warriors” as he refers to them), Pavich successfully tells the story of how this movie that almost happened – and this story alone could very well trump what the actual end product would have been. Still, it’s frustrating when all we’re left with is the mind blowing concept art of fantasy and science fiction artists H.R. Giger, Moebius and Chris Foss, not to mention the giant book of concept art and Moebius storyboards that Jodorowsky brandishes at various points in the movie. There are also the hilarious anecdotes of what went into assembling, and at times rejecting, the aforementioned team of spiritual warriors. Jodorowsky’s anecdote about meeting potential cast member Salvador Dali at the St. Regis Hotel bar in Manhattan is worth the price of admission alone.

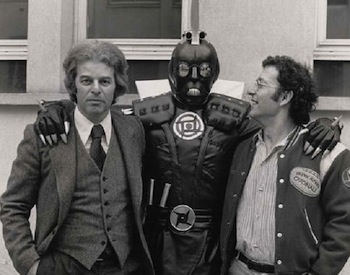

The charisma and enthusiasm of Jodorowsky is like that of a preacher or cult leader’s. It’s no wonder that he manages to convince a random crew like Orson Welles, Mick Jagger, Pink Floyd and David Carradine to join his cause. He even had his 12-year-old son undergo 2 years of extensive martial arts and weapon training in preparation to play the hero of Dune Paul Atreides, to which nobody batted an eyelash.

The charisma and enthusiasm of Jodorowsky is like that of a preacher or cult leader’s. It’s no wonder that he manages to convince a random crew like Orson Welles, Mick Jagger, Pink Floyd and David Carradine to join his cause. He even had his 12-year-old son undergo 2 years of extensive martial arts and weapon training in preparation to play the hero of Dune Paul Atreides, to which nobody batted an eyelash.

It’s said that Jodorowsky would go to extreme lengths during his previous films to ensure that his cast would be completely loyal to his vision, like holing up the central cast of The Holy Mountain in his home for a month in mental preparation to be in the film. An acolyte of hallucinogenic spirituality and various occult practices, Jodorowsky’s films are an extension of himself physically, mentally and spiritually. His version of Dune would have wildly strayed from the source material, while at the same time it would have been born from a similar place where the spiritual and imagination intersect.

Would his version of Dune have changed the world if it were made? We’ll never know. (Though his crew of spiritual warriors did go on to immediately make Alien with Ridley Scott right after – amongst many other now-classic science fiction films.) The documentary shows how copies of the production book making the rounds in Hollywood probably inspired many elements of a multitude of famous entries of the genre. It managed to change the world without having been made.

Jodorowsky’s Dune is a visual document of imagination. Jodorowsky even makes a valid argument towards the end of the movie about how the bottom dollar has sucked the imagination out of many mainstream science fiction films (and many films in general). If you’ve ever conceived of an ambitious creative project with your friends, or spent an afternoon dreaming about worlds or countries far away, or tried to write a book or song in your spare time, or simply believe in the power of imagination, then you owe it to yourself to see Jodorowsky’s Dune.

———

Follow Michael Edwards on Twitter @edwardsdeuce.