Have You Seen the Yellow Sign?

In 1938, Raymond Chandler published a short detective story called “The King in Yellow.” It takes its name from the victim, a musician named King Leopardi. When the hotel dick, Steve Grayce, finds the man shot to death in his bed, clothed in yellow silk pajamas, he remarks, “The King in Yellow. I read a book with that title once.”

———

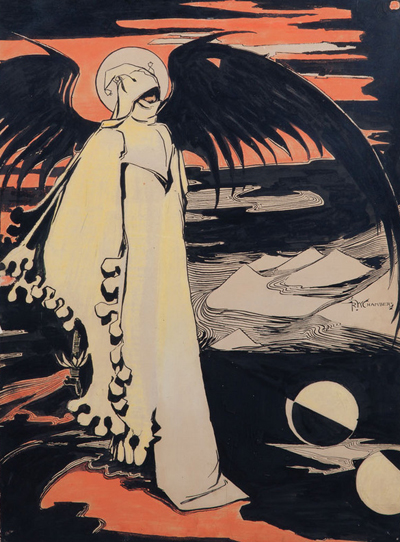

The King in Yellow, Robert W. Chambers’ 1895 collection of short stories, is having a moment in popular consciousness thanks to its role in the HBO series True Detective and the countless articles online claiming that the book is the key to understanding the show’s gloomy mystery. However, fans of the show that have snatched up the eBook offered on Amazon.com were likely disappointed in this regard.

Of the ten stories in the book, only four explicitly involve the sinister play called “The King in Yellow.” That drama involves the downfall of a royal family at the hands of the titular king, a living god who dwells in the remote and ruined city of Carcosa. Those who read the play, of which Chambers provides the reader only the merest of glimpses, find their world changed and themselves cast in the role of its characters, always to a tragic end.

Of the ten stories in the book, only four explicitly involve the sinister play called “The King in Yellow.” That drama involves the downfall of a royal family at the hands of the titular king, a living god who dwells in the remote and ruined city of Carcosa. Those who read the play, of which Chambers provides the reader only the merest of glimpses, find their world changed and themselves cast in the role of its characters, always to a tragic end.

As weird tales, they are beautiful examples, deeply concerned with delusion and the breakdown of identity, but as clues to unravel the mystery of True Detective they seem rather lacking. Chambers evokes a gilded world of bustling cities populated by bohemian artists and probes at its tarnished underbelly. More than anything else, the sex and death and despair present in The King in Yellow represent a tension between ebbing Victorian prudery and the rise of the Decadence movement in the later half the Nineteenth Century. It is not so much the tatters of the King we should fear, but rather the fleshy excesses of Huysmans, Wilde, Baudelaire and Beardsley.

The speculative fiction of “The Repairer of Reputations,” with its suicide booths and an Imperial Dynasty of America, seems particularly far removed from the bayous of True Detective’s Louisiana.

Perhaps, then, The King in Yellow isn’t a key so much as it is just one bend in a long and curving river.

———

The wellspring of that river is the author, journalist and scathing satirist Ambrose Bierce, who wrote two short stories that contain elements Chambers later used in his King in Yellow stories.

The first is the forgettable parable “Haita the Shepherd,” which gave us the name Hastur in the form of a benevolent god of shepherds. More important is “An Inhabitant of Carcosa,” in which a man ponders mortality among the stones of a ruined city. Many things that crop up Chambers appear here first – Carcosa, Hali, Alar, as well as the prominence of the Hyades and the star Aldebaran.

The first is the forgettable parable “Haita the Shepherd,” which gave us the name Hastur in the form of a benevolent god of shepherds. More important is “An Inhabitant of Carcosa,” in which a man ponders mortality among the stones of a ruined city. Many things that crop up Chambers appear here first – Carcosa, Hali, Alar, as well as the prominence of the Hyades and the star Aldebaran.

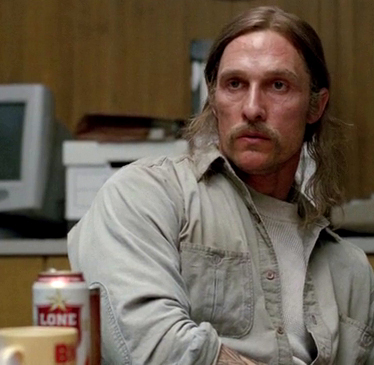

Those are just nouns, though. Bierce’s lasting contribution to this particular strain of horror is the alienation that hounded him his entire life. He was a Union veteran of the Civil War and never forgot the horrors he saw on the battlefields, nor did he forgive himself for the lives he took. As a young man, he had a dream that served as the inspiration for “An Inhabitant of Carcosa,” which he later put to verse – and sounds like something Detective Rustin Cohle (Matthew McConaughey) might quote:

Man is long ages dead in every zone

The angels all are gone to graves unknown

The devils, too, are cold enough at last

And God lies dead before the great white throne.

———

The river grows widest when it comes upon H.P. Lovecraft. Chambers’ greatest innovation was treating the play “The King in Yellow” as if it was real and using the quotations from it to tantalize the reader. Lovecraft turned this trick into a bumper industry, writing dozens of stories with his own fictional book, The Necronomicon, acting as herald for countless living gods.

In fact, Lovecraft’s backwoods blasphemies have more in common with True Detective than Chambers’ rarefied art studios. The twig sculptures would not be out of place in the wild hills of rural Dunwich. And the crazed, furtive figure of Reggie Ledoux, with his knowing smile and muttered mumbo jumbo, is cut from the same cloth as Old Castro, the talkative mestizo cultist who is arrested during a raid on a ritual in a Louisiana bayou during “The Call of Cthulhu.”

In fact, Lovecraft’s backwoods blasphemies have more in common with True Detective than Chambers’ rarefied art studios. The twig sculptures would not be out of place in the wild hills of rural Dunwich. And the crazed, furtive figure of Reggie Ledoux, with his knowing smile and muttered mumbo jumbo, is cut from the same cloth as Old Castro, the talkative mestizo cultist who is arrested during a raid on a ritual in a Louisiana bayou during “The Call of Cthulhu.”

So too is Rustin Cohle the very picture of a Lovecraftian ‘hero:’ pale, gaunt, haunted. He is disconnected from people, burdened with knowledge and too aware of the futility of it all. The edge of sanity is at his toes. He even talks like Lovecraft. “The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far.” HPL or Cohle?

It isn’t squamous tentacle monsters (bless them, though) or books of eldritch knowledge that make Lovecraft’s stories great, it is his notion of Cosmicism that ensured his enduring legacy in horror. It is a philosophy characterized by the indifference of the Universe and humanity’s insignificant place within it:

There are no absolute values in the whole blind tragedy of mechanistic nature—nothing is good or bad except as judged from an absurdly limited point of view. The only cosmic reality is mindless, undeviating fate—automatic, unmoral, uncalculating inevitability. As human beings, our only sensible scale of values is one based on lessening the agony of existence.

———

As the river winds on, we hit rapids and more authors appear.

In “The Return of Hastur,” August Derleth tries to strip the Cosmicism out of what he calls the Cthulhu Mythos – a grand unification theory tying together every story ever written by an author using Lovecraftian themes. He does this by re-introducing Hastur and the King in Yellow as good guys opposed to the nefarious machinations of Cthulhu and his allies, reducing the terrifying indifference of the universe to the black hat/white hat binary of a western.

Meanwhile, Karl Edward Wagner,  in his novella “The River of Night’s Dreaming,” returns to the idea of the play spilling over into reality and forcing its roles upon the delusional and insane. James Blish, in the darkly humorous “More Light,” penned the play itself, de-fanging the beast.

in his novella “The River of Night’s Dreaming,” returns to the idea of the play spilling over into reality and forcing its roles upon the delusional and insane. James Blish, in the darkly humorous “More Light,” penned the play itself, de-fanging the beast.

“More Light” is the strangest entry into the evolution of “The King in Yellow.” The framing story is about how disappointing it is to finally read in entirety something so many authors had only hinted at, and yet it somehow transcends itself. The details in “More Light,” make Chambers’ original stories even better, like salt on a steak.

For instance, one of Chambers’ few quotes from the play is during a masquerade, when the princess Camilla bids the Stranger in their presence to unmask, to which the stranger replies, “I wear no mask.” Camilla, naturally, responds in terror.

Blish cleverly builds to that moment in an earlier act, perhaps undermining his story’s thesis that the full text of the play is as harmless as it seems:

Stranger: …and the Pallid Mask protects me – as it will protect you.

Cassilda: How?

Strange: It deceives. That is the function of a mask.

———

The river empties out into an estuary swamp. So many authors, good and bad, are at play in the court of the King now, it is impossible to trace the individual currents.

The river empties out into an estuary swamp. So many authors, good and bad, are at play in the court of the King now, it is impossible to trace the individual currents.

The misanthropic Thomas Ligotti looms large here, the ruined edifices of his settings sinking into the morass. The burned out church from the second episode of True Detective, its shattered roof like a broken wing, is one of his. Disintegration and decay is the cosmic brush with which Ligotti works:

…whatever was submitting to its essential impermanence, its transitory nature, whatever was teetering on the brink of non-existence that was the fate of everything that had been and awaited everything that would be…every person, every place, every purpose, and every plan that could possibly be conceived.

Laird Barron is here too, with his insidious permutation of cosmic horror in which character development is wielded like a weapon. Barron embraces the full spectrum of human nature, painting his characters vividly, sympathetically and in three dimensions. The only thing they have in common is the myopia that blinds them to the outré terrors and broken systems that eventually devour them whole. Barron’s characters have much in common with Marty Hart (Woody Harrelson), but the endings always read like Rust Cohle.

When the suicidal narrator of “More Dark” attends an obviously supernatural reading by a horror author, he:

…lurched to the bar…the bartender didn’t meet my eye when I demanded a shot. He grabbed a fresh bottle of Johnnie Walker and shoved it at me. I cracked the seal and had a pull worthy of Lee Van Cleef and Lee Marvin combined, and listed against the rail, gasping for breath, and for a few moments this distracted me from whatever malevolent shit the puppet was spouting.

But he doesn’t leave. Leaving would mean missing the inexorable conclusion. Like our detectives, Barron’s protagonists can’t turn away, no matter how much they pretend to be aloof.

———

If the core of The King in Yellow is about the fragility of identity, now, nearly 120 years later, the King has collected so many masks he can be whatever he wants to be.

———

At the edge of the swamp, just short of the sea, lies True Detective.

As much as I would love the series to end with a glimpse of the tattered robes of the King in Yellow, I am just as happy to not have some incomprehensible beastie be the root of Rust and Marty’s case. The show isn’t called True Weirdness, after all.

As much as I would love the series to end with a glimpse of the tattered robes of the King in Yellow, I am just as happy to not have some incomprehensible beastie be the root of Rust and Marty’s case. The show isn’t called True Weirdness, after all.

Just because you’re in the river doesn’t mean you must be of the river. The genealogy of weird fiction informs and contextualizes the show’s themes and philosophies, perhaps, but it gets you no closer to figuring out the identity of the killer. To hone in on The King in Yellow and be so sure you’ve cracked the show’s secret code because of it means you’re missing a damn fine bit of detective fiction unfolding every week.

In the parlance of that genre, it is a red herring, a distraction, the trap of the post-Lost world, where everything is everything.

———

And beyond True Detective is the sea, where all the threads flow together and eventually evaporate, to fall once again as rain upon the mountains.

Like Rustin Cohle, and Reggie Ledoux said: time is a flat circle.

———

Recommended Reading

Where possible, I’ve linked to versions of the stories available for free on the internet. All other links, in print or otherwise, are to Amazon. I have never handled so many books working on a single column before…

“An Inhabitant of Carcosa,” by Ambrose Bierce

“The Yellow Sign,” by Robert W. Chambers – The most perfect of Chambers’ King in Yellow stories.

“The Repairer of Reputations,” by Robert W. Chambers

“The Yellow Wallpaper,” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman – A masterful 1899 tale of madness and delusion, included to underscore the connotations the color yellow had during the period.

“The Call of Cthulhu,” by H.P. Lovecraft

“The Whisperer in the Darkness,” by H.P. Lovecraft – One of the few stories Lovecraft explicitly mentions the Yellow Sign and other Chambers creations. It also marks one of the earliest instances of a conscious human brain being kept alive in a jar.

“The Dunwich Horror,” by H.P.Lovecraft – “The Dunwich Horror” is about as good guy vs. bad guy as Lovecraft ever got, and overall the story suffers for it. Instead of a tale of cosmic dread, it reads a more typical supernatural adventure yarn. However, the descriptions of the backwater rural folk, their history and their customs are incredibly atmospheric, especially when compared to True Detective.

“The King in Yellow,” by Raymond Chandler – This is the original version of the story text, with Steve Grayce as the protagonist. Chandler later re-wrote the story to feature Philip Marlowe.

New: “The Great God Pan,” by Arthur Machen – There isn’t a lot in this story, one of the greatest horror tales ever written, that parallel’s True Detective, but I couldn’t help thinking about it an awful lot during the first episode. It was something about the spaghetti man chasing girls in the woods. Read it and decide for yourself.

New: “Who Goes There?” by John W. Campbell – The literary source material for The Thing movies, the story plays out much the same way as John Carpenter’s 1982 adaptations, alien doppelgangers and all (though, in the story, there’s more cows). In terms of True Detective, it is interesting to note that the fourth episode, one very much preoccupied with the mutability of identity, bears the same name.

***

From The Hastur Cycle

“The Return of Hastur,” by August Derleth – I hesitate to put this story on the list. Derleth was actually a very capable horror writer, but you would never know it from this dreck.

“The River of Night’s Dreaming,” by Karl Edward Wagner

“More Light,” by James Blish

“Tatters of the King,” by Lin Carter – These fragments chronicle Carter’s attempts to reconcile all versions of the Yellow Mythology, from Bierce to Blish.

***

“Scene: A Room,” by Craig Anthony – For better or worse, this is an interesting example of the synthesis between the King in Yellow and what has become known as the Cthulhu Mythos. It only saw publication once, in Cthulhu’s Heirs, which is now out of print.

***

Thomas Ligotti

“Professor Nobody’s Little Lectures on Supernatural Horror” – An oft-overlooked Ligotti tale that probes the weaknesses of the fourth wall in ways similar to how “The King in Yellow” is supposed to operate. It only saw print in Ligotti’s Songs of a Dead Dreamer, which is currently only available in a Kindle version.

“The Tsalal” – Human beings rarely seem to be the focus of Ligotti’s stories. Rather he dwells on the bizarre workings of outré forces and the oppressive atmosphere of ruined places. “The Tsalal” has no shortage of both, and a MacGaffin evil book to boot! Currently only available in the Kindle version of Noctuary.

My Work is Not Yet Done – The quotation used in this story is from Ligotti’s grim take on the Japanese aesthetic concepts of wabi and sabi. It also happens to be one of the most disgusted screeds against corporate culture ever put to paper.

***

Laird Barron

“D T” – Not my favorite of Barron’s stories, but one with explicit ties to The King in Yellow. The unnamed author, a reformed biker, could very well be Ginger, if he makes it to the present day. Published in the anthology A Season in Carcosa, a volume of strangely low production quality but promising contents – I admit I have not had a chance to read most of it at this point.

“More Dark” – True Detective shares a kind of drunken, masculine swagger with many of Barron’s stories. To date, this is one of his drunkest. Collected in (and the namesake for) The Beautiful Thing that Awaits Us All.

“The Men from Porlock” – Also in The Beautiful Thing that Awaits Us All. Not particularly tied to True Detective or The King in Yellow – it just happens to be my current favorite Laird Barron story. Sue me.

New: “Bulldozer” – Just finished this one about a Pinkerton agent investigating a series of Satanic ritual murders that features not only the quote “time is a ring,” but a clever construction to support that notion. If you want a Laird Barron story that seems to have direct parallels to True Detective, this is the one. Available in The Imago Sequence.

———

Stu Horvath has a first edition of The King in Yellow, but it doesn’t match any of the known versions of the book (no, he isn’t kidding). If you know something about that, give him a shout on Twitter @StuHorvath.