Paratext: Just Shut Up

Nathan Drake talks too much.

His dialogue is well-written. Nolan North, his voice actor, delivers the lines with character. And very little of it is po-faced exposition delivered with a gravitas inversely proportional to how relevant it is to what you’re about to do in the game. But his quipping, it tires me out.

There’s a school of thought that suggests that a silent protagonist doesn’t get in the way of player identification. The idea is that the player is in full (or almost-full) control of the character’s actions and allowing the character to speak without the player initiating it is not consistent with the rest of the player/character relationship. As most videogame development has historically been aimed at modeling physics rather than rhetoric (a legacy of their beginnings as combat simulators, maybe, or they’re being code at their core, or maybe that’s just where many of their developer’s interests lie), player control of their character’s conversational ability is usually significantly less developed than their control of their character’s “physical” ability.

There’s a school of thought that suggests that a silent protagonist doesn’t get in the way of player identification. The idea is that the player is in full (or almost-full) control of the character’s actions and allowing the character to speak without the player initiating it is not consistent with the rest of the player/character relationship. As most videogame development has historically been aimed at modeling physics rather than rhetoric (a legacy of their beginnings as combat simulators, maybe, or they’re being code at their core, or maybe that’s just where many of their developer’s interests lie), player control of their character’s conversational ability is usually significantly less developed than their control of their character’s “physical” ability.

There’s another visual media tradition that these characters fall into – the silent protagonist in film. The man of action (always a man in both games and in film, because masculine silence is a choice). His actions are honest – they are what they are. Words can refer to things that aren’t present, to things that haven’t happened. Words can’t be trusted. A fist to the face: you can’t lie that into or out of existence.

But words? Words lie.

———

This didn’t start with John Wayne, but we might as well.

Wayne’s popular persona, the American cowboy, the strong and silent hero, the avatar of Masculinity, is actually more nuanced in his films (those produced by his company Batjac Productions notwithstanding). He provided a certain class of American Man a template on which to model himself during and after World War II. That little global conflict screwed up “traditional” (read: Victorian and Industrial Revolution era) gender roles for entire classes of Americans.

It was a retread: when Wister wrote The Virginian in 1902 and Grey wrote Riders of the Purple Sage in 1912, the American West had been mostly settled (in a white-people-live-here-now sense) decades before. The cowboy was gone in many real historical senses; he stuck around, though, to symbolize another (allegedly) vanishing role: masculinity.

It was a retread: when Wister wrote The Virginian in 1902 and Grey wrote Riders of the Purple Sage in 1912, the American West had been mostly settled (in a white-people-live-here-now sense) decades before. The cowboy was gone in many real historical senses; he stuck around, though, to symbolize another (allegedly) vanishing role: masculinity.

Super-strict gender roles were part of a specific class of society in the early 1900s, there were domestic and public spheres post-Industrial Revolution and male preachers were shouting against the “feminization” of Christianity. The cowboy could ride in and save the men’s day.

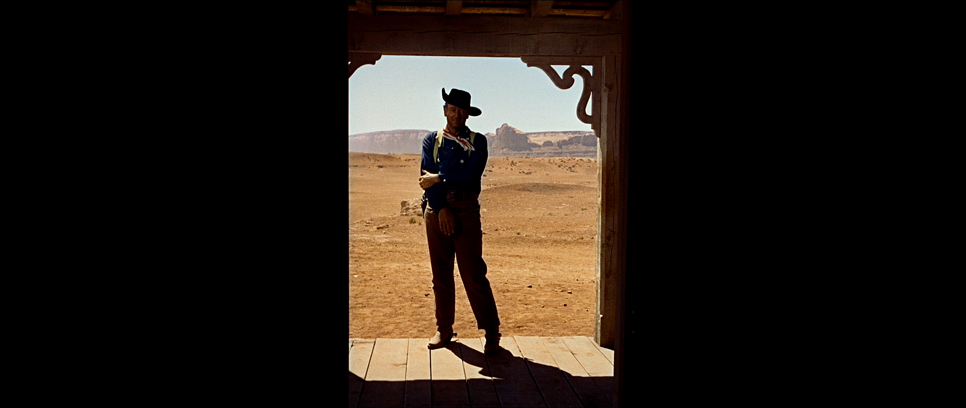

But as I said above, even Wayne, even Hollywood, could make things more complicated than that (deconstruction in the American Western didn’t start with Unforgiven, no matter how much simpler things would be if it had). His super-racist Ethan is left outside in The Searchers (1956), while Marty (whose ancestry is both white and Native American) and Debbie (who was kidnapped and raised by Native Americans) are welcomed into the home. No one stops to point this out; no one says, “Ethan, there’s no place for you here, in this civilized world.” He stands in the doorway, backlit, peering into the place he cannot go.

The visual is a thesis statement: there is a kind of masculinity that may have been important in the past but is incompatible with the social world. Maybe it eased anxieties people feel about not belonging. And don’t even get me started on Shane (1953), which is so clearly a fantasy of the cowboy, or Johnny Guitar (1954), which stars Joan Crawford…

See, here’s the thing about the silent cowboy: he really needed film. A novel can imply all this stuff about how words are dangerous and untrustworthy and unmanly, but there’s kind of a problem when, you know, novels are made of words. But with an image, you can put him up on a screen and he never has to say two words and – BAM – that tension is instantly resolved.

See, here’s the thing about the silent cowboy: he really needed film. A novel can imply all this stuff about how words are dangerous and untrustworthy and unmanly, but there’s kind of a problem when, you know, novels are made of words. But with an image, you can put him up on a screen and he never has to say two words and – BAM – that tension is instantly resolved.

And so post-World War II anxieties about gender roles (caused or exacerbated by the return of servicemen who needed jobs and the shoving the women who had been working those jobs back into the domestic sphere) start (apparently) worshiping a Victorian public/domestic masculine/feminine split. Here, now able to be present without words, rides the cowboy.

A lot of us like our history to be simple. Whether that simplicity is in service of a more or a less enlightened world tends to depend on your political bent – is it something to return to or to run from? Thing is, it was messy. Really messy.

The point is, we remember things as being less complicated than they were, which can have an effect on the creative decisions we constantly make when building things.

———

When a videogame protagonist talks, and I mean really talks – not shouting one-liners on a loop – they’re suddenly not a cipher. Identification with the protagonist begins to rely on empathy rather than through puppetry. And empathy for a character brings empathy for that character’s world. And its inhabitants. It can de-objectify them, suggest that these bits of code and pixel have an inner life. That leads to a different kind of disconnect, one where people feel a dissonance between Nathan Drake’s happy-go-lucky adventurer and the number of people he guns down in any given area he explores (personally, I find the disconnect between how unsure of his climbing he is and how well the controls respond to what I want them to do far more irritating).

[pullquote]A novel can imply all this stuff about how words are dangerous and untrustworthy and unmanly, but there’s kind of a problem when, you know, novels are made of words.[/pullquote]

It’s risky: the more there is to identify with, the more there is to be turned away by. So many, many characters continue to be silent, long after the technology to make them speak has arrived. It gets touted as a feature, a promise that your “immersion” will never be broken. That the character will disappear and you will be present in the world.

Of course, this is a basic misunderstanding of how people relate to things outside themselves, to technology. This idea, that for you to fully embody in the game world everything that stands between you and that world must be minimized, that all apparatuses must be hidden, is what leads to things like Kinect.

Is the controller a barrier to people experiencing games? Absolutely. But the solution isn’t to make the controller disappear; it’s to train the controller to adapt to the different people as much as it is to train the people to adapt to the controller. The tool and the carpenter become one. I could pound in a nail with my bare hand, but it’s much easier, and much more effective, if there’s something between my palm and the wood.

———

I think words have power. I hope they do. To exorcise and connect and heal, as well as to mislead and hurt and destroy. Images are a language of things that aren’t there. Games are actions that aren’t there. They take doing and shove it into that cultural category of speech, where they talk and shout and try desperately to move us as we sit in front of their screens.

And you? Maybe you want to look at the screen as a window into another world – a world with its own rules, its own meanings, its own separate existence from our own. But if it is a window, it’s not looking into somewhere else. It’s very much a part of our world. It’s a stained-glass window, a visual abstraction made up of many, many, many more polygons than the ones in your standard Roman Catholic Church.

———

Paratext is an occasional column in which Brian Taylor examines the space between – and around – ideas. Follow him on Twitter @brianmtaylor, where he is anything but silent.