View From the Side

Videogame interactivity is so great.

Who wants to watch a hero when you can be the hero? That’s the promise games keep giving us on the back of the box, isn’t it? But they seldom deliver on that promise. Games welcome their players to a world, lay out a central conflict in the opening minutes and introduce the major characters who will shape the events. However, it isn’t often that the player-character is among those characters – usually he’s only associated with them.

[pullquote]The memorable scenes, one-liners, even outfits of carefully constructed-characters in just about any RPG belong to the sidekick…[/pullquote]

More often than not, a protagonist is an instrument of action, not its dictator. If playing a videogame were like building a house, the player wouldn’t be the carpenter – he’d be the hammer. Understanding a world, its conflicts, orchestrating a solution and emotionally reacting to events falls to what is mislabeled as the sidekick. PCs are just glorified letter carriers along for the ride; in fact, usually the role the player takes on is that of the sidekick.

The compelling thing about fictional characters is experiencing their autonomy in a world that somehow reflects reality. Audiences relate to heroes based on how they make decisions in their circumstances; the sidekick is there as an audience insert, an everyman to round out the real protagonist’s badassary. Many videogame protagonists don’t express their own autonomy; they exist to facilitate the player’s suspension of disbelief and to do as told by a higher authority until the plot is resolved.

Sound familiar? Even in games where players are given plenty of autonomy, the characters they occupy are usually only significant insofar as they act on behalf of more important people. The player-controlled “protagonist” just diligently goes through the motions set by some other character who is actually at the center of the stage.

For example, 2008’s Prince of Persia followed the heir of a dying sacred land in an adventure to contain an evil deity. There is also some dude walking by who promises to help. Prince of Persia’s eponymous prince has almost no impact or investment in the world – he just shows up. The real hero, Elika, is just as acrobatic as the prince and therefore as apt a platformer. She’s also at least as courageous and as clever as the player’s avatar. The only difference between the Prince and Elika is that she knows about the world, the force threatening it and the means to saving it (and her gravity-defying magic powers) where the Prince is just a wisecracking tourist taking her advice. The only thing the Prince contributes is his sword in the game’s shoddy combat. His purpose is reduced to that of the pointed stick he carries around with him.

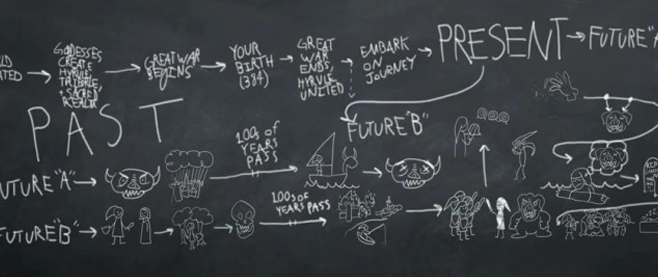

However, Prince of Persia’s Elika is only a blip on the radar compared to The Legend of Zelda. It’s in the name: the legend that Nintendo keeps spinning focuses on Zelda, not the player’s Link. Link isn’t there to save Hyrule – that’s Zelda’s job. His job is to follow the instructions left by the princess with the faith that her planning will grant a happy ending. He’s there to stand on switches, collect magic tokens and wrangle chickens, not to place counter- or preventative measures against Ganon.

However, Prince of Persia’s Elika is only a blip on the radar compared to The Legend of Zelda. It’s in the name: the legend that Nintendo keeps spinning focuses on Zelda, not the player’s Link. Link isn’t there to save Hyrule – that’s Zelda’s job. His job is to follow the instructions left by the princess with the faith that her planning will grant a happy ending. He’s there to stand on switches, collect magic tokens and wrangle chickens, not to place counter- or preventative measures against Ganon.

Link is just an instrument in Zelda’s careful machinations. Even after the princess’s inevitable capture, Link is micromanaged by a fairy sidekick along the way who ensures he’s following instructions. At any given point in the standard Zelda adventure, it’s the supposed sidekick doing the thinking and planning. Link is just her toolbox.

Like Link, a lot of game protagonists just don’t do very much in their world that isn’t listed in a quest or mission log. They don’t make their own plans and they aren’t asked to make their own judgements. Instead, they’re given a list of chores and check them off until the credits roll. Granted, there may be creative ways to check off these chores and there are games and genres that are better at giving their heroes autonomy, but often it’s the “sidekick” who’s the autonomous actor applying the protagonist to the problem like a blunt instrument.

However, PCs aren’t just sidekicks because they’re reduced to following orders with basic actions. They’re sidekicks because they don’t have the personal investment or character depth to hold a story on their own. Usually only the tagalong characters have any stake in the journey, while the PC sits at a distances and pushes through the quest list.

Most RPG “blank slate” characters are just a waypoint for interesting side characters. The standard Bethesda or BioWare protagonists are just customizable faces that act like either a pushover or an asshole. They aren’t personally involved in their tasks, nor do their interests create conflicts or force unwanted outcomes. They’re just there to get the job done. The surrounding party, however, is gushing with personality. The memorable scenes, one-liners, even outfits of carefully constructed-characters in just about any RPG belong to the sidekick, not the dull beige everyman at center stage.

For instance, throughout the Gears of War series Marcus Fenix is uniformly bland, reacting to everything with a grumpy one-sentence quip with all the gusto of Christian Bale’s Batman reading a tax form. All the real characterization – errors in judgement, flaws that impact the plot and changes in personality – happens in player 2’s Dom. Even though Dom is no more than a war hound like Marcus and the rest of Delta Squad, he’s actually invested in the games’ events. Marcus may have a father who shows up for 10 minutes in a deus ex machina at the end of the third game, but Dom actually grieves and hopes; he has a personal stake in the mission. Success or defeat means more than something else to grumble about, where Marcus is only involved in his world as much as his gun.

For instance, throughout the Gears of War series Marcus Fenix is uniformly bland, reacting to everything with a grumpy one-sentence quip with all the gusto of Christian Bale’s Batman reading a tax form. All the real characterization – errors in judgement, flaws that impact the plot and changes in personality – happens in player 2’s Dom. Even though Dom is no more than a war hound like Marcus and the rest of Delta Squad, he’s actually invested in the games’ events. Marcus may have a father who shows up for 10 minutes in a deus ex machina at the end of the third game, but Dom actually grieves and hopes; he has a personal stake in the mission. Success or defeat means more than something else to grumble about, where Marcus is only involved in his world as much as his gun.

For all the applause that games get for being an active medium, it’s worth noting how passive most PCs actually are in their own games. The character carrying the story is usually the one at the periphery of the player control – the Ashley to the player’s Leon, the Atlas to his Jack.

Players take the role of the nearest blunt object in forcing a solution out of a bad situation. PCs don’t have a direct influence on the planning stages. They aren’t participating for their reason nor are they emotionally committed to the task at hand; they don’t even respond to its progress in a very human way. In any other media, we’d call them the sidekick.