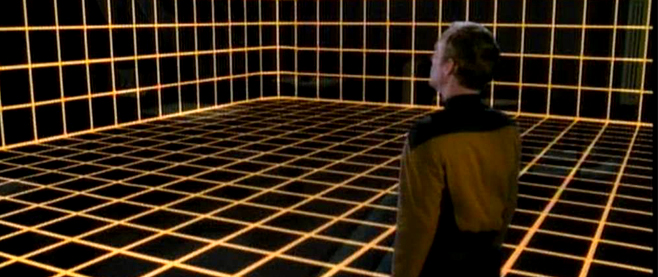

Star Trek: The Next Generation – Season 5 – “The Inner Light”

The Road Not Taken

You may tell yourself, this is not my beautiful house

You may tell yourself, this is not my beautiful wife

Letting the days go by, let the water hold me down

Letting the days go by, water flowing underground

– “Once in a Lifetime,” by the Talking Heads

“The Inner Light”, the penultimate episode of Next Gen Season 5, is the most important episode of Star Trek I’ve ever seen. At least, it is to me. It aired in 1992. It coincided with the first time my father died, and quite possibly changed my life.

But perhaps I should back up a bit. The episode is a classic self-contained piece of short science fiction, in which Captain Picard is attacked by a probe, resulting in him living out an entire alternate lifetime in the course of 25 minutes. While the bridge crew on the Enterprise bumbles around trying to bring him back, Picard experiences perhaps 40 years of a lifetime, resisting his new, very simple life on the planet Kataan, but ultimately falling in love, bearing children and experiencing a deep sense of community.

When I first saw the episode live, I was living in San Francisco with the wrong woman, in a rental house I couldn’t afford, driving a sports car I couldn’t afford, doing a job that I hated but paid well. I remember watching it and thinking it was overly maudlin pablum.

When I first saw the episode live, I was living in San Francisco with the wrong woman, in a rental house I couldn’t afford, driving a sports car I couldn’t afford, doing a job that I hated but paid well. I remember watching it and thinking it was overly maudlin pablum.

Some time later, I got the phone call that my surrogate father had died in a car crash.

But perhaps I should back up again.

My real father was a blackout alcoholic. At the age of 14, I walked out of the house in a blizzard and never went back. I lived with friends for a bit, my grandmother for a summer, but ultimately just struck out on my own in college. I was not a stable or particularly whole person. One summer, needing both employment and a roof, my best friend’s uncle “hired” me to work on his house, doing odd jobs, building picnic tables and painting.

Al.

Al was a Vietnam vet who’d lost half a hand in the war (I called him Berek, in honor of the Stephen Donaldson series, but never to his face). He was a rock & roll relic of the ’60s. He played bass. His house was a constant flow of guests and parties and hospitality. He was a Christian, albeit a reluctant and questioning one. He cooked. He was a fantastic husband and father.

And he became the closest thing to a father I’ve ever had.

When he died, I hadn’t spoken to him in about six months. He’d steered me from my aimless teens towards the man I’d become at the age of 24. I’d avoided the big traps: I’d graduated. I’d done well in school. I’d gotten sensible jobs and even gone to business school. These were fantastic alternatives to becoming a drug-addled poet living in a shack in the hills of Western Massachusetts, which is likely where I was headed without Al’s influence.

But my last interactions with Al suggested his disappointment. Our last phone call ended with him saying something to the effect of, “It’s great you’re doing so well, Jules. Just don’t forget who you are and where you’re from, OK? And come visit.”

When I got the call that he had died, I hopped on a plane, rented a car and came home. To those hills of Western Massachusetts. I diligently went to the funeral, shed my tears. When the funeral was over, my friends asked me to go out with them, have a few drinks and tell stories. I begged off and drove straight back to the airport.

Somewhere in southwest Connecticut I pulled over the dumb sports car I’d rented and started sobbing. Not the tears of loss, but a full-on nervous breakdown of uncontrollable gasping. And I remembered Star Trek:

PICARD: Please… if you could tell me… what is this place? Where am I?

“The Inner Light” does what the very best speculative fiction has always done. It takes a hook of a morsel of the real and it pushes it as far as it can go. Picard’s false reality – the one that invades his head and supplants his identity with that of a lowly iron weaver named Kamin – is not welcome.

PICARD: Just tell me this – am I a prisoner here?

It’s a shock to the system. And it’s one that changes who he is. He’s forced into a kind of existential withdrawal. A withdrawal from the “real” world. Even months after he’s had to accept that this dream-world is his new reality, he resists.

ELINE: You think this…your life…is a dream?

PICARD: It’s not my life…I know that much.

Picard fights for years in his alternate reality, clinging to his past. I imagine I’d last a week before my sense of dream and un-dream collapsed under the weight of my own ego. Picard’s experience is more jarring than any shock we could have here on earth, because he’s not just slapped in the face with something new, he’s excised from reality with a scalpel. He is forced through Thoreau’s Walden-Pond-knothole, stripped not only of all of his baggage but his very identity. He’s forced into a Buddhist no-mind state of identity dissolution with a nucleonic sledgehammer. But eventually, the shock to his system overwhelms his Captaincy memories and he lets himself become, well, himself.

When Picard does finally give in and inhabit Kamin, he transforms. He transforms into a husband, a father and a man of seemingly few pretensions. This is the ur-Picard, the Picard who would exist without any of the trappings of the Federation life. He, alone among all men in the universe, has this unbelievable chance to try on a different life like a pair of running shoes.

When Picard does finally give in and inhabit Kamin, he transforms. He transforms into a husband, a father and a man of seemingly few pretensions. This is the ur-Picard, the Picard who would exist without any of the trappings of the Federation life. He, alone among all men in the universe, has this unbelievable chance to try on a different life like a pair of running shoes.

Sitting there on the side of the road, wearing a life that was all too real but fit like a Walmart suit, I couldn’t help but think of Al’s last words – not to lose who I was for the sake of the real world. As I sat there in the dumb sports car, I realized I wasn’t really crying for myself or Al anymore, but for Picard. Seriously. Every moment of that lifetime he experiences is one of profound tragedy in two dimensions. While he grows to love a woman deeply, raise a family and truly become part of a community, that entire experience is crowded out by the knowledge that everything in that life is doomed by the impending nova of Kataan’s sun. And yet, that doomed life is seemingly fuller and richer, and certainly less sterile than any part of his life as Captain. As Kamin, Picard lives the life he could have been living all along. One filled with less Tea-Earl Grey-Hot and more frivolous flute-playing and grandchild-tickling. And yet, we see little evidence that Picard changes, following his own advice to his ersatz daughter, to always make “now” the most precious time.

PICARD: Live now, Meribor. Always make “now” the most precious time. “Now” will not come again.

I won’t say that I woke up the next morning and changed my life in a heartbeat. But that moment on the roadside – just me, Al and Picard, taking inventory of 24-year-old Julian Murdoch and finding him rather wanting – was a turning point. I would resist for a few years, until I finally realized I could craft a life that was more natural, more loving and more rewarding. One full of family and rock & roll. One with a constant flow of guests and parties and hospitality. One of a reluctant and questioning Christian. One where I could be a husband and father.

I still cry at the end of “Inner Light.” But I’m not weeping at the death of worlds, the lost lifetime, or even Picard’s failure to take a lifetime of change back into the 24th century. Mostly, I just miss Al.

———

Follow Julian Murdoch on Twitter @GWJRabbit.